Real-to-Reel: Social Indexicality, Sonic Materiality, and Literary Media Theory in Eduardo Costa’s Tape Works

by Tom McEnaney

The essay begins:

In 1968, Vogue magazine featured an unusual new accessory. Ear (1966), a 24-karat gold anatomical replica that entirely covered model Marisa Berenson’s own ear, was one of a number of fitted extensions—there was also a finger, a toe, and strands of gold hair—that Argentine-born artist Eduardo Costa included in his Fashion Fiction 1. Photographed by Richard Avedon on one of Vogue’s most famous models, Costa’s jewelry—part sculpture, part ornamental prosthetic—attempted to parody the fashion industry even as it was absorbed into its pages. Playful and seductive, Ear wavered on the boundary—quickly eroding in 1968—between high-end fashion and vanguard art. At its most critical, Ear and other Fashion Fictions by Costa literalized the familiar reification of commodity culture: turning human body parts into objects, the works winked at fashion’s claim to be an extension of yourself. In repurposing the language of fashion, they also made sense in the Vogue of the late 1960s alongside the work of Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and other artists. For, like these contemporaries in pop art or works from the Latin American neo-baroque, Costa’s ornaments reveled in the surface rather than condemning the superficial. This fascination with surfaces found an ideal corollary in Avedon’s photography, which celebrated the foreground. With Ear, Avedon’s portrait of Berenson became an almost mythic testament to the “statuesque” model, whose image recalls both a passing victim of Midas’s touch and a Galatea on the verge of breaking into the auditory world

If Ear stopped there, however, we could stack Costa’s Fashion Fictions alongside Oldenburg’s everyday objects or Warhol’s Brillo Boxes—all three artists shared work at the Fashion Show Poetry Event held at the Center for Inter-American Relations in New York in January of 1969. But Ear distinguishes itself from pop art standards not so much for its send-up of commodity culture, as through its emphasis on the auditory image. This sculpture, or ornament, or prosthetic shows what it doesn’t tell: sound is everywhere implicit but nowhere physically present in the work. Asking its viewers to look at listening, Ear transforms the apparently ephemeral world of sound into a physical object.

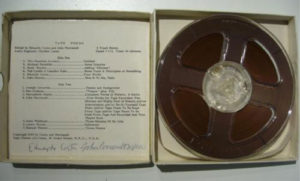

This objectification of sound, whose effect on the wearer, it’s worth remembering, would be to mute or dull audition, ties in to the revolution in materializing sound in the 1960s. Like our own moment’s explosion of new technologies and formats for producing and consuming sound, postwar innovations in audio engineering, largely linked to the emergence of newly popular recording materials such as magnetic tape, renewed older concerns about fidelity and the realism of reproduced sound. Yet, notably different from most current criticism of digital sound’s apparent loss of fidelity, the 1960s technologies helped produce the cult of high fidelity, renewing nineteenth-century discourses of sonic fidelity and the belief that sound reproduction could become indistinguishable from the recorded source.

As I will explain in greater detail in what follows, Costa’s work at this time went beyond sculpture and concept to draw from new sound recording technologies’ ability to register and (re)produce sonic phenomena, and to bind these transformations to language and literature. In terms familiar to media studies, just as photography or film’s chemical imprint of the sun’s rays onto photographic negatives indexed physical traces of light, high fidelity seemed to expand what Friedrich Kittler would celebrate as the gramophone’s ability to inscribe the material “real” of sonic vibrations onto cylinders or shellac discs. Yet, while Kittler declared that electrical sound recording tolled the death knell of literature, Costa’s tape recording work in the late 1960s fuses the material index of media studies with what linguistic anthropologist Michael Silverstein calls the “non-referential social indexicality” available in language. Such social indexicality exists, for example, in the sonic attributes of a voice that can index a speaker’s age, nationality, sex, and so on. Against what has often been understood as the impasse between literature and media in the wake of Kittler, Costa brings together these two sides of the index to create a literary media theory and practice based in sound recording. Continue reading …

This article develops a linguistic media theory that brings together Peircean materialist indexicality from Barthes, Bazin, Doane, Krauss, and others with linguistic anthropologist Michael Silverstein’s nonreferential (social) indexicality. Following Argentine sound artist Eduardo Costa’s practice with tape recording, the article challenges critical theory to account for the sonic meaning at play in pragmatic (nonsemantic) communication related to gender, race, and diasporic community. More than a mere supplement or limit, material sonic media expand aesthetic representation, and media archaeology opens new possibilities to intervene in language politics.

TOM McENANEY is Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature at Cornell University. He is the author of several articles and the forthcoming book Acoustic Properties: Radio, Narrative, and the New Neighborhood of the Americas (Flashpoints Series, Northwestern University Press, 2017).

TOM McENANEY is Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature at Cornell University. He is the author of several articles and the forthcoming book Acoustic Properties: Radio, Narrative, and the New Neighborhood of the Americas (Flashpoints Series, Northwestern University Press, 2017).