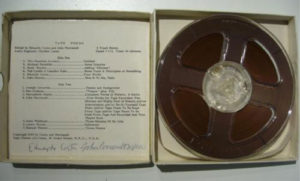

“A Good Communist Style”:

Sounding Like a Communist in Twentieth-Century China

by M. Paulina Hartono

In this essay Paulina Hartono focuses on the history and politicization of radio announcers’ vocal delivery in China during the mid-twentieth century. She explores how Chinese Communist Party leaders used internal party debates, national policies, and broadcasting training to construct an ideal Communist voice whose qualities would ostensibly communicate party loyalty and serve as a sonic representation of political authority.

The essay begins:

Shortly after the Communists took power in China, three of the most famous radio broadcasters in their respective countries met together to discuss their experiences: Yuri Levitan and Olga Vysotska of the Soviet Union and Qi Yue of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Vysotska stated that the duty of their profession was “to find the shortest route to the people’s hearts.”[i] The idea that one ought to use one’s voice to move people was not lost on Qi. Radio broadcasters played a major role in the nation-state, both as the literal mouthpieces of the party and as transmitters of a carefully crafted sound. In an environment where political campaigns were pushed into a visual landscape of posters, banners, illustrated leaflets, and the like, an auditory world of early-PRC socialist political culture was taking shape. Radio broadcasters’ pronouncements were significant not only for their discourse—what they said—but also for their representation—how they sounded.

This essay examines the construction of a particular way of speaking in the People’s Republic of China by studying its most notable mouthpieces—its broadcasters. Directed to make their announcements “accurate, fresh, and lively,” these radio broadcasters were encouraged to be engaging to listen to, and, given the very audible platform they occupied, they also became national models of how to speak. Compared to the number of visual studies of Cold War China, sound studies are relatively few and focus mainly on the 1960s and 1970s. By contrast, this essay looks at China during the 1940s and 1950s during the early Mao period. Unlike the radio voice of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), the voice of the PRC was less an index of class or education than a symbol of political belief. These particular and constructed vocal qualities were formalized and reinforced by radio announcers and propaganda officials following major national events, including war, national linguistic reform, and targeted political campaigns.

One of the difficulties of studying aural cultural production is synesthetic, as it is a slippery task to describe sonic qualities in discursive forms. Mladen Dolar once called voice the “remainder which cannot be made a signifier or disappear in meaning; the remainder that doesn’t make sense, a leftover, a cast-off . . . of the signifier.” Recent developments in the emerging field of voice studies reveal a rich and diverse range of research methodologies, including voice as a physical phenomenon (for example, laryngeal dynamics), as a sensory perception (cognitive processing of sound), and as a mediation through technology (such as the Auto-Tune processor). Moreover, as a political act, voice can map and reproduce an intricate system of coded power relations between speaker and listener, including those evident in class conflict, race relations, and gendered politics. As Miyako Inoue has argued in her deconstruction of Japanese women’s language, when culturally accepted notions of vocal qualities are ascribed to groups and not denaturalized, they can project static traditions and archetypes where dynamic cultural and political forces are actually present.

From the earliest years of the People’s Republic of China, officials saw radio as a tool for political and ideological education. The sounds of broadcasters’ voices were themselves exercises in a political education. They projected an imagined voice of the nation by using the national standardized accent and a sonic affect to project affinity with ordinary citizens, or “the People,” vaunted in Chinese Communist Party (CCP) culture and propaganda. Warmth, strength, and confidence were qualia that were closely associated with the voice and what it signified. Ultimately, and especially during the Anti-Rightist Campaign, radio announcers’ vocal qualities became synecdochal with their political personhood, purporting to reveal their own internal thoughts and feelings. Announcers needed to deploy the right pronunciation, energy, and emotion in order to express the full embodiment of the true believer in delivering radio content. In the eyes of propaganda department officials, failure to communicate properly could reveal a lack of commitment to the party.

Beyond China, the vocal styles in Soviet bloc radio seem to have shared a “socialist soundscape”: in the USSR, radio broadcasting grew out of a tradition that held the accent of the Moscow proletariat as its standard; even recently, in North Korea, the famed newscaster Ri Chun-hee has become well known for her emotionally charged broadcasts. Whether in China or elsewhere in the bloc, radio announcers were supposed to represent the voices of socialist-realist heroes, demonstrating that language ideology could convey more than discourse, grammar, and content. Continue reading …

M. PAULINA HARTONO is a scholar of Chinese science and technology, history, and media cultures and a doctoral candidate in history at the University of California, Berkeley. Her research examines the history of radio broadcasting and reception in twentieth-century China.

ANNA SHECHTMAN

ANNA SHECHTMAN In this a bold new account of how celebrity works, Marcus draws on scrapbooks, personal diaries, and vintage fan mail to trace celebrity culture back to its nineteenth-century roots, when people the world over found themselves captivated by celebrity chefs, bad-boy poets, and actors such as the “divine” Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923), as famous in her day as the Beatles in theirs.

In this a bold new account of how celebrity works, Marcus draws on scrapbooks, personal diaries, and vintage fan mail to trace celebrity culture back to its nineteenth-century roots, when people the world over found themselves captivated by celebrity chefs, bad-boy poets, and actors such as the “divine” Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923), as famous in her day as the Beatles in theirs.

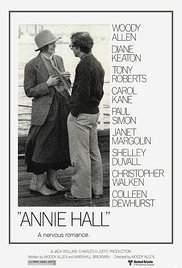

In Woody Allen’s romantic comedy Annie Hall (1977), the world’s most famous technological determinist had a brief cameo that in some circles is as well-known as the movie itself. Woody Allen, waiting with Diane Keaton in a slow-moving movie ticket line, pulls Marshall McLuhan from the woodwork to rebuke the blowhard in front of them, who is pontificating to his female companion about McLuhan’s ideas. McLuhan, as it happened, was not an easy actor to work with: even when playing a parody of himself, a role he had been practicing full-time for years, he couldn’t remember his lines, and when he could remember them, he couldn’t deliver them. In the final take (after more than fifteen tries), McLuhan tells the mansplainer, “I heard what you were saying. You, you know nothing of my work. You mean my whole fallacy is wrong. How you ever got to teach a course in anything is totally amazing.” In the film, the ability to call down ex cathedra authorities at will to silence annoying know-it-alls is treated as the ultimate in wish fulfillment as Allen says to the camera, “Boy, if life were only like this!” Rather than a knockout punch, however, McLuhan tells the man off with something that sounds like a Zen koan, an obscure private joke, or a Groucho Marx non sequitur. There is more going on here than a simple triumph over someone else’s intellectual error. Isn’t a fallacy always self-evidently wrong?

In Woody Allen’s romantic comedy Annie Hall (1977), the world’s most famous technological determinist had a brief cameo that in some circles is as well-known as the movie itself. Woody Allen, waiting with Diane Keaton in a slow-moving movie ticket line, pulls Marshall McLuhan from the woodwork to rebuke the blowhard in front of them, who is pontificating to his female companion about McLuhan’s ideas. McLuhan, as it happened, was not an easy actor to work with: even when playing a parody of himself, a role he had been practicing full-time for years, he couldn’t remember his lines, and when he could remember them, he couldn’t deliver them. In the final take (after more than fifteen tries), McLuhan tells the mansplainer, “I heard what you were saying. You, you know nothing of my work. You mean my whole fallacy is wrong. How you ever got to teach a course in anything is totally amazing.” In the film, the ability to call down ex cathedra authorities at will to silence annoying know-it-alls is treated as the ultimate in wish fulfillment as Allen says to the camera, “Boy, if life were only like this!” Rather than a knockout punch, however, McLuhan tells the man off with something that sounds like a Zen koan, an obscure private joke, or a Groucho Marx non sequitur. There is more going on here than a simple triumph over someone else’s intellectual error. Isn’t a fallacy always self-evidently wrong? JOHN DURHAM PETERS

JOHN DURHAM PETERS