From Radio to Radio-visione: Italian Radio’s Television Experiments, 1939–1940

by Danielle Simon

In this study, Danielle Simon investigates a series of experimental television broadcasts undertaken by Italian Fascism’s national broadcasting entity, the Ente Italiano per le Audizioni Radiofoniche, in the years leading up to the Second World War. She explores both the official autarchical policies and the technological limitations that shaped the radio network’s early experiments with television to show that producers’ attitudes regarding medium specificity shaped decisions about programming and musical content. She goes on to suggest that these early sorties into televisual broadcasting left traces that can be seen in the style and political clout of Italian television even today.

In this study, Danielle Simon investigates a series of experimental television broadcasts undertaken by Italian Fascism’s national broadcasting entity, the Ente Italiano per le Audizioni Radiofoniche, in the years leading up to the Second World War. She explores both the official autarchical policies and the technological limitations that shaped the radio network’s early experiments with television to show that producers’ attitudes regarding medium specificity shaped decisions about programming and musical content. She goes on to suggest that these early sorties into televisual broadcasting left traces that can be seen in the style and political clout of Italian television even today.

The essay begins:

On 22 July 1939, viewers crowded into the television viewing room of the Villaggio Balneare (“bathing village”) set up in Rome’s Circus Maximus, sponsored by the television companies SAFAR and Fernseh. Six television sets, described by one Roman newspaper as somewhere between a mirror and a large radio, lined one wall. Spectators stood shoulder to shoulder in the packed hall, craning their necks to glimpse the images on these screens, each of which measured less than half the size of today’s 42-inch televisions. From the inset speakers rang the lilting tones and rollicking antics of Italian radio’s most popular musical performers and comedians. The crowd gasped, laughed, and applauded as the stars whose voices had graced their homes for more than a decade appeared to them for the first time on the small screen.

The images that so entranced the audience, and the devices that captured them, were the result of more than a decade of effort on the part of the Ente Italiano per le Audizioni Radiofoniche (EIAR), the radio broadcasting arm of the Fascist regime. EIAR had maintained exclusive control over Italian airwaves since its creation in 1927. Initially, EIAR’s subscriber list numbered around forty thousand, but that number jumped to more than one million by the end of the 1930s as the network worked to reach new listeners, particularly those located in rural areas, who were deemed especially valuable by the Fascist government. But even as Italian radio extended its reach and expanded its audiences, pressure came from the regime and from listeners to unite sound and image in the form of broadcast television. As early as 1929—only five years after the first Italian radio broadcast—engineers Alessandro Banfi and Sergio Bertolotti conducted experiments in transmitting images over radio waves from EIAR studios. A decade later, these experiments in “radio-vision” would lead to the events just described—the first transmission of images over radio waves, visible to the public from a viewing room.

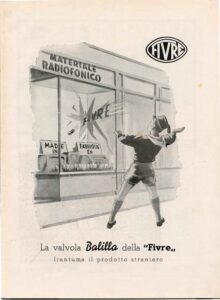

More than simply another way to entertain EIAR’s growing population of subscribers, these experimental broadcasts served as evidence of Italian Fascism’s standing on the world stage. The Magneti Marelli equipment used for the transmissions, developed in consultation with engineers from the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), was regularly cited as proof of Italy’s rapid technological development, and thus of the nation’s hard-won progress. EIAR lauded the political value of the television experiments in the pages of its weekly magazine, Radiocorriere, boasting that the television broadcasts were “the greatest, most curious attraction” within the exhibition, and a manifestation of “Fascist spirit.” By10 August, the Roman newspaper Il Messaggero reported that the Villaggio Balneare had seen at least twelve thousand visitors, nearly all of whom had visited the viewing room to marvel at the new technology. The spectacle demonstrated television’s ability to showcase “the most beautiful and vigorous images of the Italian race and art” and catapulted Italian technologies into the global marketplace.

What follows is a history of disappointment. Despite the network’s lofty ambitions, EIAR’s television experiments were short lived, discontinued less than two years after they began. Italian networks would not attempt television transmission again until a decade later. Yet the broadcasts revealed a politics of spectacle that placed images, seeing, and being seen at the center of modern political life. Events like EIAR’s television experiments reveal a much tighter linkage among culture, technology, commerce, and politics than is typically attributed to Fascist cultural policy or practice. In this article, I will explore the official policies, technological limitations, aesthetic premises, and programming decisions that shaped the radio network’s early experiments with television, ultimately suggesting that these early sorties into televisual broadcasting left traces that continue to shape the style and political clout of Italian television. Continue reading …

DANIELLE SIMON is a postdoctoral fellow at the Dartmouth Society of Fellows. She is a former fellow of the American Academy in Rome (2016–2017) and received her doctorate in musicology from the University of California, Berkeley, in 2020. Her research interests include emerging media technologies and musical performance, particularly opera, and radio broadcasting during the years of Fascism in Italy. Her current book project examines transnational radio broadcasts from Italy to the United States and Latin America during and after the Fascist period.