The Metapragmatics of the “Minor Writer”: Zoë Wicomb, Literary Value, and the Windham-Campbell Prize Festival

by Aaron Bartels-Swindells

The essay begins:

In the festival program for the 2013 Windham-Campbell Prize for Literature, Zoë Wicomb, a South African writer primarily known for her work during the postapartheid era, construed her success as “impossible. For a minor writer like myself, this is a validation I would never have dreamt of.” The prizes, given by Yale University, are among the most lucrative individual cultural awards in the world, worth $150,000 each, and the honor was well publicized: in addition to generating global media coverage, Yale hosted a four-day festival that included a prize ceremony and reading. Wicomb’s self-identification as a “minor writer” seems slightly paradoxical in light of such publicity and remuneration. What, then, does “minor writer” signify? How is that significance shaped by broader frameworks that change throughout time and space?

In the festival program for the 2013 Windham-Campbell Prize for Literature, Zoë Wicomb, a South African writer primarily known for her work during the postapartheid era, construed her success as “impossible. For a minor writer like myself, this is a validation I would never have dreamt of.” The prizes, given by Yale University, are among the most lucrative individual cultural awards in the world, worth $150,000 each, and the honor was well publicized: in addition to generating global media coverage, Yale hosted a four-day festival that included a prize ceremony and reading. Wicomb’s self-identification as a “minor writer” seems slightly paradoxical in light of such publicity and remuneration. What, then, does “minor writer” signify? How is that significance shaped by broader frameworks that change throughout time and space?

My approach to these questions understands signification as the effect and effectiveness of social action. My adoption of language-in-use methodologies is inspired by Wicomb’s pragmatist analyses of contemporary South African literature and culture, which demonstrate an acute sense of how utterances interact with contexts fashioned through social action. In one such essay, “Shame and Identity: The Case of the Coloured in South Africa,” Wicomb examines how contemporary discursive formulations are produced by and engender “coloured” shame. She uses the past and present of coloured shame to consider the fate of South Africa’s “youthful postcoloniality,” analyzing “ethnographic self-fashioning” and “discursive construction by others” in relation to “the narrative of liberation and its dissemination in the world media that constructed oppression in particular ways.” This formulation provides the impetus to consider how narratives about oppression emanate and are taken up in ways that effect localized articulations of identity. Wicomb’s paper encourages us to examine the significance of the “minor writer”—and its poetic resonances with “minority”—in relation to her claim that “the newly democratized South Africa remains dependent on the old economic, social, and also epistemological structures of apartheid, and thus it is axiomatic that different groups created by the old system do not participate equally in the category of postcoloniality.” We should also think about how the term “minor writer” functions in relation to Wicomb’s literary works, following her discussion of the deleterious influence that these epistemological structures and narratives about oppression have on metropolitan reading strategies that stress cultural hybridity.

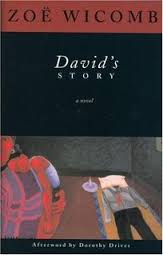

Wicomb’s second novel, David’s Story, from which she read at the Windham-Campbell Prize (henceforth WCP) festival, stages many of her concerns about shame, cultural hybridity, the effacement of history, and the past and present status of women in the struggle for justice in postcolonial society. The novel, according to critic Dorothy Driver, is “self-consciously positioned as a postmodernist text” and “dramatize[s] the literary, political, philosophical and ethical issues at stake in any attempt at retrieval of history and voice.” Set in 1991, after the release of Nelson Mandela, and told by a nameless amanuensis, the narrative weaves a number of related plots that imply connections between past and present around that of David Dirkse, a former guerilla of the African National Congress (ANC), who, after the unbanning of the movement, researches the history of his coloured roots. The segment that Wicomb chose to read does not mention David and is drawn from the second narrative of David’s Story, which is about a “minor Griqua chief.” How does this excerpt from the narrative function in relation to Wicomb’s self-description as a “minor writer”?

Wicomb’s second novel, David’s Story, from which she read at the Windham-Campbell Prize (henceforth WCP) festival, stages many of her concerns about shame, cultural hybridity, the effacement of history, and the past and present status of women in the struggle for justice in postcolonial society. The novel, according to critic Dorothy Driver, is “self-consciously positioned as a postmodernist text” and “dramatize[s] the literary, political, philosophical and ethical issues at stake in any attempt at retrieval of history and voice.” Set in 1991, after the release of Nelson Mandela, and told by a nameless amanuensis, the narrative weaves a number of related plots that imply connections between past and present around that of David Dirkse, a former guerilla of the African National Congress (ANC), who, after the unbanning of the movement, researches the history of his coloured roots. The segment that Wicomb chose to read does not mention David and is drawn from the second narrative of David’s Story, which is about a “minor Griqua chief.” How does this excerpt from the narrative function in relation to Wicomb’s self-description as a “minor writer”?

This article considers postapartheid narratives of liberation and the activity of parsing a text in relation to the creation and circulation of literary and social value. Thus, while I focalize my discussion through the term “minor writer,” my aim is to understand how the expression functions in relation to the schemata of value to which its usage points. The article proceeds in two parts. The first examines how two distinct usages of “minor writer” index different schemata of social knowledge. From Wicomb’s use of the phrase in an interview from 2002 about writing and nation, I explicate how “minor writer” articulates a self-reflective orientation to the intersection of literary and social value in South Africa. I then contrast this usage with the section on Wicomb from the WCP program, which effects a transformation of social value by yoking representations of Wicomb’s literary persona and voice to a particular kind of chronotopic formulation of South Africa. My reading of this artifact demonstrates how microdescriptions of Wicomb and her work evoke macroconstructions of South African society, a process that occludes Wicomb’s self-positioning in the earlier interview. The second part asks how discourses from the WCP festival concerning value circulate beyond it, and whether they affect how we read texts that move between schemata of value. At stake throughout is how the power to consecrate literary value is metapragmatically constituted and contested in relation to the term “minor writer.” Continue reading …

How does the significance of Zoë Wicomb’s description of herself as a “minor writer” in the 2013 Windham-Campbell Prize festival program contrast with her other uses of the term? Arguing that the term’s usage at different times and places indexes distinct schemata of value, I examine the program as an artifact that sediments a certain formulation of Wicomb’s literary persona and provides affordances for parsing her literary works.

AARON BARTELS-SWINDELLS is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at the University of Pennsylvania.