Crossed Geographies: Endō and Fanon in Lyon

By Christopher L. Hill

Textual evidence indicates that the novelist Endō Shūsaku read the anticolonialist writer Frantz Fanon in the early 1950s, incorporating Fanon’s arguments on color and colonialism into his depiction of Japanese subjects after 1945. In this essay, examination of that heretofore unnoticed encounter provides an opportunity to reconsider the paradigms by which each writer is understood today and the terms in which they imagined a world not ordered by empires, whether European, American, or Japanese.

The author writes:

“The paths writers trace in the world tell as much about the geographies scholars give them as the geographies they lived. Figures of international repute pass each other unnoticed if the conventions under which we labor don’t allow a meeting. Once acknowledged, such encounters are an opportunity. Unexpected encounters reveal greater forces at work; new questions demand answers. Through crossed paths we can see the world in a different shape, but only if we are willing. In disciplinary and conceptual terms, we shy away from the leap of scale that making sense of an encounter between, say, a novelist from Japan and an anticolonialist from Martinique requires. It is easier to blow up or clone—to ‘globalize’ a national field or to deploy a theory anew—than to struggle toward a geohistorical problematic, a transnational frame for criticism, that would not reduce the unevenness and heterogeneity of the geography of lived experience to a comforting, because familiar, model. Two discomforting journeys may suggest the way.

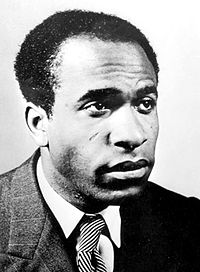

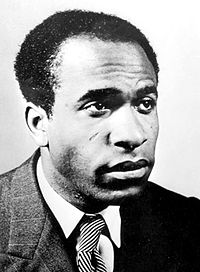

“In early 1943 Frantz Fanon, who later became famous for his writings on colonial psychology and the struggle against colonialism, dropped out of his lycée and took a boat from Martinique to Dominica, where he hoped to join the Free French army. He was sent home, but the following March, after Martinique rallied to Charles de Gaulle, he sailed for Morocco with some one thousand volunteers. Fanon told a teacher that when freedom was at stake, all were concerned—but only the officers and some of the noncommissioned officers onboard were white; the rest of the volunteers were black. In the training camp in Morocco, soldiers from Martinique and Guadeloupe (‘old’ French colonies) ate the same food and wore the same uniforms as white soldiers; they lived apart from recruits from Morocco, Algeria, and sub-Saharan Africa. Fanon and his friends quickly saw that the army that had been formed to fight fascism had a racial hierarchy: whites at the top, North Africans at the bottom, and black West Indians ambiguously above the African Tirailleurs sénégalais in the middle. When Fanon’s unit decamped to Algeria in July, he discovered that the locals loathed black men. By the time he was fighting in France, in autumn, he was doubting his position between European soldiers and the Tirailleurs, because the black soldiers seemed to face the worst action. In January 1945 he wrote his brother that his reasons for joining up had been wrong; in April he wrote his parents the same.

“In early 1943 Frantz Fanon, who later became famous for his writings on colonial psychology and the struggle against colonialism, dropped out of his lycée and took a boat from Martinique to Dominica, where he hoped to join the Free French army. He was sent home, but the following March, after Martinique rallied to Charles de Gaulle, he sailed for Morocco with some one thousand volunteers. Fanon told a teacher that when freedom was at stake, all were concerned—but only the officers and some of the noncommissioned officers onboard were white; the rest of the volunteers were black. In the training camp in Morocco, soldiers from Martinique and Guadeloupe (‘old’ French colonies) ate the same food and wore the same uniforms as white soldiers; they lived apart from recruits from Morocco, Algeria, and sub-Saharan Africa. Fanon and his friends quickly saw that the army that had been formed to fight fascism had a racial hierarchy: whites at the top, North Africans at the bottom, and black West Indians ambiguously above the African Tirailleurs sénégalais in the middle. When Fanon’s unit decamped to Algeria in July, he discovered that the locals loathed black men. By the time he was fighting in France, in autumn, he was doubting his position between European soldiers and the Tirailleurs, because the black soldiers seemed to face the worst action. In January 1945 he wrote his brother that his reasons for joining up had been wrong; in April he wrote his parents the same.

“Fanon returned to Martinique in late 1945 and finished his baccalaureate. With funds provided for veterans’ education, he sailed late the next year for Paris, where he planned to study dentistry. He left Paris abruptly a few weeks after arriving there and went on to Lyon, where he enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine at its university, specializing in psychiatry. He read widely, attended classes by Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and gave some lectures of his own. In May 1951 he published ‘The Lived Experience of the Black Man’ (‘L’Expérience vécue du noir’), an essay on Antillean men’s discovery that in France they were considered to be black. He took a temporary post in Dôle while he finished his thesis, which he defended at the end of November. He spent several weeks in Martinique in February and March 1952, but, deciding against practicing there, he returned to France and took a post at the clinic in Saint-Alban run by François Tosquelles, where he developed the foundations of his social psychiatry. In February he published an essay on the psychosomatic illnesses of North African men in Lyon, ‘The North African Syndrome’ (‘Le Syndrome nord-africain’), and in June, Black Skin, White Masks (Peau noire, masques blancs). (‘The Lived Experience of the Black Man’ was its fifth chapter.) After another temporary assignment in 1953, he took a post in Blida in Algeria, where he moved in November, and began learning about the struggle against French rule; in 1955 he began his work with the anticolonial Algerian National Liberation Front. He never returned to Martinique.

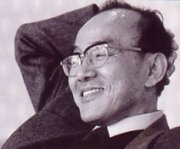

“In June 1950, Endō Shūsaku, who later became famous for fiction about Catholicism, began a journey in a different part of the world that, like Fanon’s, took him to Lyon. The first leg was a fourth-class voyage from Yokohama to Marseille. As Endō observed in his diary, relations among the passengers were determined by wealth, race, and the hierarchies of Western colonialism. A group of African soldiers from the French colonial army shared his compartment. They were returning to Saigon after escorting war criminals to Japan. During several port calls, Endō, and other Japanese students too, were treated as war criminals by local authorities. In Manila they were assembled on deck, while Filipinos on the docks shouted ‘Murderers!’ and ‘Assholes!’ in Japanese. In Singapore they were forbidden to disembark. While passing through the Suez Canal he learned of North Korea’s invasion of the South and US President Harry Truman’s order to intervene. After arriving in Marseille, Endō spent July and August with a Catholic family in Rouen, where he encountered a Japan-hating young man whose brother had served in Indochina during the Asia-Pacific War.

“In June 1950, Endō Shūsaku, who later became famous for fiction about Catholicism, began a journey in a different part of the world that, like Fanon’s, took him to Lyon. The first leg was a fourth-class voyage from Yokohama to Marseille. As Endō observed in his diary, relations among the passengers were determined by wealth, race, and the hierarchies of Western colonialism. A group of African soldiers from the French colonial army shared his compartment. They were returning to Saigon after escorting war criminals to Japan. During several port calls, Endō, and other Japanese students too, were treated as war criminals by local authorities. In Manila they were assembled on deck, while Filipinos on the docks shouted ‘Murderers!’ and ‘Assholes!’ in Japanese. In Singapore they were forbidden to disembark. While passing through the Suez Canal he learned of North Korea’s invasion of the South and US President Harry Truman’s order to intervene. After arriving in Marseille, Endō spent July and August with a Catholic family in Rouen, where he encountered a Japan-hating young man whose brother had served in Indochina during the Asia-Pacific War.

“In September Endō settled in Lyon, where he enrolled at the Catholic University and the University of Lyon’s Faculty of Letters to study French Catholic writers. In the streets Endō encountered plaques marking locations where fighters in the French Resistance had fallen; he also learned about a massacre of civilians by the Resistance in the town of Fons. His experiences on ship and the traces of the Resistance in France pushed him in the following years to write several stories, two novellas, and a novel about collaboration, resistance, and war crimes in France and Japan. Twice in 1952 Endō spent time in sanatoria in the Alps for tuberculosis. He moved to Paris in the autumn of that year and was hospitalized there in December. One of the patients in his four-bed room, a veteran, berated Endō with memories of his treatment by the Japanese army in Indochina. In January 1953 he departed Marseille for Japan because of his health. In 1954 he published a semi-autobiographical story called ‘As Far as Aden’ (‘Aden made’), about a Japanese student’s time in France, where he discovered he was un jaune, a yellow man, in the eyes of French whites….

“Yet the geographies of each writer’s lived experience are not as distinct as those in which scholarship presently confines them. The circumstances that shaped their writings on color and colonialism were at once personal and part of a history that encompassed both the Caribbean and East Asia. Reading Endō’s work through Fanon’s, and Fanon’s through Endō’s, reveals a mid-twentieth-century history of race and racialization on a large (I will not say global) scale. In this history decolonization and what should be called the de-imperialization of Japan by the victors in the Asia-Pacific War are entangled with the demise of the European empires and the rise of the American. The transformations coincided with manifold changes in the social meanings of black, white, and yellow and the rights associated with them. A history and a criticism in which this kind of encounter is plausible and meaningful must dismantle the analytically separate problematics of anticolonialism and decolonization, on the one hand, and of “postwar” and the Cold War in Asia, on the other. Reconstructing the history that connects Endō and Fanon does more than historicize these two writers’ early works. It suggests too what can be gained from an intellectual history and a criticism that ignores divisions more constructed than real while acknowledging, rather than trying to reconcile, the heterogeneous and sometimes contradictory qualities of the geography that results.” Continue reading …

CHRISTOPHER L. HILL is Assistant Professor of Japanese literature at the University of Michigan. The author of National History and the World of Nations: Capital, State, and the Rhetoric of History of Japan, France, and the United States (Durham, 2008), he is currently completing a book on the transnational career of the naturalist novel and beginning a project on Japanese writers in the “Bandung moment” of the 1950s.