Hebdomadal Form: Diaries, News, and the Shape of the Modern Week

by David Henkin

The essay begins:

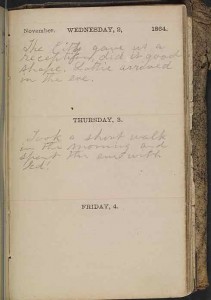

On a September Saturday in 1846, Alabama medical student Charles Hentz scrambled to account for lost time in his diary. “As I have been negligent for another week, in keeping up my journal,” he wrote, he resolved to revisit the events of the past seven days. “I must make a kind of Hebdomary.” The following May, Hentz again referred to his “regular hebdomary,” excusing his failure to live up to the diary-keeping habits he had undertaken a year earlier with a distinctive lexical diversion and a common practical refrain. “So many things occupy me during the week, that I find it impossible to be regular in my journal.” Hentz was hardly alone among nineteenth-century American diarists in noting that weekly intervals often separated the entries in a book defined around the norm of daily regularity. The diary genre reckoned and homogenized days, but users habitually inscribed additional temporal patterns in their pages.

The particular weekly pattern that Hentz observed in his own handling of the diary impulse evokes a familiar modern temporality of retrospective accounting. It is utterly commonplace to consider the week in review, to take stock of our lives in seven-day inventories. But the power of that accounting practice reflects a larger and generally overlooked development in the history of timekeeping in the West over the past few centuries. As saints’ days, market days, informal festivity, seasonal rhythms, and other systems and strategies of calendrical differentiation declined in Western Europe, North America, and elsewhere, the regularity of the seven-day week became more conspicuous.

The particular weekly pattern that Hentz observed in his own handling of the diary impulse evokes a familiar modern temporality of retrospective accounting. It is utterly commonplace to consider the week in review, to take stock of our lives in seven-day inventories. But the power of that accounting practice reflects a larger and generally overlooked development in the history of timekeeping in the West over the past few centuries. As saints’ days, market days, informal festivity, seasonal rhythms, and other systems and strategies of calendrical differentiation declined in Western Europe, North America, and elsewhere, the regularity of the seven-day week became more conspicuous.

The historical significance of this development remains clouded by the week’s status as an anomalous institution in the history of modern time reckoning. The week is in one sense an ancient regime, often invoked by traditional cultural critics as a bulwark against the encroachments of modernity. But it is also a mechanical tracking device, indifferent to natural rhythms, that has proven especially congenial to market relations, capitalist reorganization of labor, the demands of long-distance communication, and the cultural logics of impersonal society—including the oft-cited homogeneity of time associated with the industrial era. The ostensibly homogeneous days of industrializing America, for example, conformed to a rigorously observed seven-day cycle and were marked in complex ways by their placement in that cycle. Even as the image of daily repetition enshrined itself in modern consciousness as a compelling symbol of ordinary activity and uneventful occurrence (expressed in metaphorical invocations of the quotidian and the everyday), seven-day rhythms and seven-day intervals helped organize the modern regime of the day. Modern weekly rhythms are complex historical artifacts, rooted in long histories of liturgy and labor. But they are also entrained in literary practice and encoded in texts. It is worth considering how proliferating habits of reading and writing may have helped confer weekly form upon daily order. Continue reading …

The spread and intensification of seven-day regimes remains a remarkable and understudied feature of the making of modernity. This essay explores the role of written form in that historical process in the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century, arguing that diaries and newspapers, two literary genres associated with the construction of the day as a measure of temporal significance, also registered and reinforced awareness of the week as a structuring rhythm in ordinary life.

DAVID HENKIN, Professor of History at UC Berkeley, is the author of City Reading, The Postal Age, and (with Rebecca McLennan) Becoming America.