Transducing a Sermon, Inducing Conversion:

Billy Graham, Billy Kim, and the 1973 Crusade in Seoul

by Nicholas Harkness

The essay begins …

In the spring of 1973, the American evangelist Billy Graham traveled to Seoul, South Korea, for one of his famous crusades. The evangelical campaign took place on Yoido, an island along the Han River. Although this island would emerge over the next decades as a dense urban center of government, finance, and broadcasting, in 1973 it still was largely an empty plot of sandy earth. General Pak Chung-hee, the autocratic ruler of South Korea from 1961 until his assassination in 1979, gave permission for organizers to hold their crusade on an asphalt expanse on Yoido that was used for official state events and military demonstrations. Prior to that, the area had been used as an airstrip by the US military and, earlier, by the Japanese colonial government. On May 30, the first day of the event, more than 300,000 people attended. Each day, the crusade grew in attendance. On June 3, the fifth and final day, Graham preached to a crowd estimated to exceed one million (fig. 1). It was the largest crowd ever amassed for a Billy Graham event.

Next to Billy Graham at the pulpit, and backed by a choir of 6,000 singers, was Billy Jang Hwan Kim, the South Korean minister of Suwŏn Baptist Church, who reproduced Graham’s sermon verbally and peri-verbally—utterance by utterance, tone by tone, gesture by gesture—for the Korean-speaking audience. Kim explained in his autobiography that he watched film footage of Billy Graham’s preaching so that he could “practice the accents, gestures, and intonations of Billy Graham” in order to “become a Korean-speaking Billy Graham” for those five days. In documentary footage of the event, Kim explained that while his own style at the pulpit was different from Graham’s, for those five days he did not want to “divert,” “change,” or make Graham’s message “any different” from what or how Graham preached. Kim described the interactional effect of interpreting for Billy Graham as two voices becoming one voice. He explained this accomplishment in supernatural terms: “Well, once I got in with him, I didn’t even know what I was doing. And I think I was completely influenced by the force that, uh, you know, we call the Holy Spirit.”

Christian leaders in South Korea praised Kim’s performance. Pastor Kim Kyong Nae, secretary general of the crusade, described Kim’s interpretation as capturing Graham’s “spiritual flow” (yŏngchŏk in hŭrŭm) and characterized the interaction of the two preachers as one of “harmony.” Pastor Pang Chi Il, a member of the organizing committee for the crusade, claimed that Kim had not translated Graham’s sermon (pŏnyŏk) at all. Rather, according to Pastor Pang, Kim seemed to have given his own sermon, which, Pang claimed, is why it had made such a deep impression (kammyŏng) on the audience. There was similar praise from US Christians who witnessed Kim’s performance. According to Billy Graham’s official biographer, “Billy Kim actually enhanced Billy Graham. In gesture, tone, force of expression, the two men became as one in a way almost uncanny. A missionary fluent in Korean who knew Graham personally thought that Kim’s voice even sounded like Graham’s. Some TV viewers, tuning in unawares, supposed Kim the preacher and Billy Graham the interpreter for the American forces.” Henry Holley, Billy Graham’s Crusade Director for Asia, put it simply: “The two of them functioned as one.” At a press conference during his trip to Seoul, Graham himself thanked the thousands in Korea who had been “working and praying and preparing” for the success of the crusade and then added: “And I would be absolutely nothing were it not for my good voice, Billy Kim.”

I have two aims for this paper. First, I want to reveal in detail the semiotic processes of synchronization and calibration by which Billy Kim’s sequential interpretation of Billy Graham’s sermon into Korean for a Korean-speaking audience had the semiotic effect of fusing two voices into one. These processes complicate the question of “who” was speaking at any given moment, and they suggest that we must investigate higher-order cultural frameworks that make these processes semiotically legitimate for participants. Second, I attempt to demonstrate how this semiotic fusion of voices drew upon and intensified the very ideological principles of evangelism that brought these two men to the pulpit and justified their speech in Seoul in 1973. As I explain in detail in what follows, this analysis hinges on our methodological expansion from the narrow translation of denotational text to a broader semiotic “transduction” of indexicality through which denotational text emerges interactionally. Although I cannot adequately represent the virtuosity of the performance, my analysis focuses on the dynamic pragmatics of this historic event documented in a film recording that captures the increasingly dense layering of temporal and spatial deixis across codes, the compounding of vocalizations and figurative voicings across speakers, and the way these semiotic dimensions of preaching linked theological principles of radical universality to personal experiences of radical individuation. Continue reading …

This paper is an analysis of the final sermon of Billy Graham’s 1973 Crusade in Seoul, South Korea, when he preached to a crowd estimated to exceed one million people. Next to Graham at the pulpit was Billy Jang Hwan Kim, a preacher who, in his capacity as interpreter, translated Graham’s sermon verbally and peri-verbally—utterance by utterance, tone by tone, gesture by gesture—for the Korean-speaking audience. I examine the dynamic pragmatics (for example, chronotopic formulations, deictic calibrations, voicing and register effects, and indexical dimensions of entextualization) by which a sermonic copy across linguistic codes became an evangelical conduit between Cold War polities. In so doing, I demonstrate how the scope of intertextual analysis can be expanded productively from the narrow translation of denotation across codes to the broader indexical processes of semiotic “transduction” across domains of cultural semiosis.

NICHOLAS HARKNESS is John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Social Sciences in the Department of Anthropology at Harvard University.

In the festival program for the 2013 Windham-Campbell Prize for Literature, Zoë Wicomb, a South African writer primarily known for her work during the postapartheid era, construed her success as “impossible. For a minor writer like myself, this is a validation I would never have dreamt of.” The prizes, given by Yale University, are among the most lucrative individual cultural awards in the world, worth $150,000 each, and the honor was well publicized: in addition to generating global media coverage, Yale hosted a four-day festival that included a prize ceremony and reading. Wicomb’s self-identification as a “minor writer” seems slightly paradoxical in light of such publicity and remuneration. What, then, does “minor writer” signify? How is that significance shaped by broader frameworks that change throughout time and space?

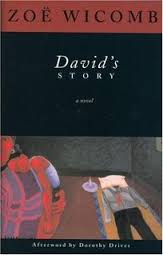

In the festival program for the 2013 Windham-Campbell Prize for Literature, Zoë Wicomb, a South African writer primarily known for her work during the postapartheid era, construed her success as “impossible. For a minor writer like myself, this is a validation I would never have dreamt of.” The prizes, given by Yale University, are among the most lucrative individual cultural awards in the world, worth $150,000 each, and the honor was well publicized: in addition to generating global media coverage, Yale hosted a four-day festival that included a prize ceremony and reading. Wicomb’s self-identification as a “minor writer” seems slightly paradoxical in light of such publicity and remuneration. What, then, does “minor writer” signify? How is that significance shaped by broader frameworks that change throughout time and space? Wicomb’s second novel, David’s Story, from which she read at the Windham-Campbell Prize (henceforth WCP) festival, stages many of her concerns about shame, cultural hybridity, the effacement of history, and the past and present status of women in the struggle for justice in postcolonial society. The novel, according to critic Dorothy Driver, is “self-consciously positioned as a postmodernist text” and “dramatize[s] the literary, political, philosophical and ethical issues at stake in any attempt at retrieval of history and voice.” Set in 1991, after the release of Nelson Mandela, and told by a nameless amanuensis, the narrative weaves a number of related plots that imply connections between past and present around that of David Dirkse, a former guerilla of the African National Congress (ANC), who, after the unbanning of the movement, researches the history of his coloured roots. The segment that Wicomb chose to read does not mention David and is drawn from the second narrative of David’s Story, which is about a “minor Griqua chief.” How does this excerpt from the narrative function in relation to Wicomb’s self-description as a “minor writer”?

Wicomb’s second novel, David’s Story, from which she read at the Windham-Campbell Prize (henceforth WCP) festival, stages many of her concerns about shame, cultural hybridity, the effacement of history, and the past and present status of women in the struggle for justice in postcolonial society. The novel, according to critic Dorothy Driver, is “self-consciously positioned as a postmodernist text” and “dramatize[s] the literary, political, philosophical and ethical issues at stake in any attempt at retrieval of history and voice.” Set in 1991, after the release of Nelson Mandela, and told by a nameless amanuensis, the narrative weaves a number of related plots that imply connections between past and present around that of David Dirkse, a former guerilla of the African National Congress (ANC), who, after the unbanning of the movement, researches the history of his coloured roots. The segment that Wicomb chose to read does not mention David and is drawn from the second narrative of David’s Story, which is about a “minor Griqua chief.” How does this excerpt from the narrative function in relation to Wicomb’s self-description as a “minor writer”? Vernacular poetry is generally evaluated according to culturally specific aesthetic standards, what anthropologists call ethnopoetics. This article offers embodied entexualization—the culturally specific ways bodies are incorporated into as well as produce texts—as a means for analyzing how ethnopoetic systems reflect social and political histories and contexts. The poetry of the northern Italian town of Bergamo, and specifically a poem by a locally celebrated poet, Piero Frér, provides an illustrative case.

Vernacular poetry is generally evaluated according to culturally specific aesthetic standards, what anthropologists call ethnopoetics. This article offers embodied entexualization—the culturally specific ways bodies are incorporated into as well as produce texts—as a means for analyzing how ethnopoetic systems reflect social and political histories and contexts. The poetry of the northern Italian town of Bergamo, and specifically a poem by a locally celebrated poet, Piero Frér, provides an illustrative case.

D. A. Miller

D. A. Miller