Heartfelt Musicking: The Physiology of a Bach Cantata

by Bettina Varwig

The essay begins:

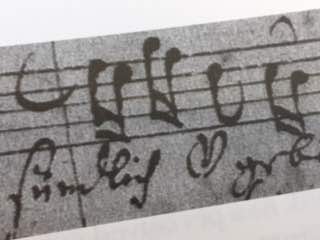

There is a notational oddity in the autograph score of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cantata 199, “Mein Herze schwimmt im Blut” (My heart is swimming in blood). Instead of writing out the word “heart” every time it appears in the text, at several points the composer used the familiar heart symbol—not exactly shaped like the physical organ, but apparently as instantly recognizable then as it is now. In some instances, the abbreviation may have resulted from pragmatic considerations of space, but in others clearly not. Instead, perhaps Bach was invoking, in an inconsequential and semi-private manner, the rich significatory potential of this pictogram. Already by the early seventeenth century, the heart image had come to appear frequently in a variety of contexts, from courtly chivalry and religious iconography to sets of playing cards, encompassing an extensive field of associations and meanings. Severed from the human body, the organ could be subjected to a dazzling variety of treatments, as in the extraordinary Emblemata sacra (1622) by the German Lutheran theologian Daniel Cramer. In this widely distributed volume of devotional emblems, the heart appears in no fewer than fifty different scenarios, demonstrating its protean capacity to stand in for the believer’s life, soul, conscience, consciousness, memory, earthly existence, or inner self: the heart as a rock being softened by God’s hammer, a winged heart escaping from the claws of earthly demons up to heaven, the heart with a seeing eye, Jesus inscribing his name on the heart, the heart adrift in a stormy sea, a burning heart filled with cooling liquid from the Holy Spirit, the heart’s mettle being tested in a hot oven, and so on.

There is a notational oddity in the autograph score of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cantata 199, “Mein Herze schwimmt im Blut” (My heart is swimming in blood). Instead of writing out the word “heart” every time it appears in the text, at several points the composer used the familiar heart symbol—not exactly shaped like the physical organ, but apparently as instantly recognizable then as it is now. In some instances, the abbreviation may have resulted from pragmatic considerations of space, but in others clearly not. Instead, perhaps Bach was invoking, in an inconsequential and semi-private manner, the rich significatory potential of this pictogram. Already by the early seventeenth century, the heart image had come to appear frequently in a variety of contexts, from courtly chivalry and religious iconography to sets of playing cards, encompassing an extensive field of associations and meanings. Severed from the human body, the organ could be subjected to a dazzling variety of treatments, as in the extraordinary Emblemata sacra (1622) by the German Lutheran theologian Daniel Cramer. In this widely distributed volume of devotional emblems, the heart appears in no fewer than fifty different scenarios, demonstrating its protean capacity to stand in for the believer’s life, soul, conscience, consciousness, memory, earthly existence, or inner self: the heart as a rock being softened by God’s hammer, a winged heart escaping from the claws of earthly demons up to heaven, the heart with a seeing eye, Jesus inscribing his name on the heart, the heart adrift in a stormy sea, a burning heart filled with cooling liquid from the Holy Spirit, the heart’s mettle being tested in a hot oven, and so on.

As the seat of life and the source of sin, the heart in the Christian tradition mediated between flesh and spirit. It could taste, sing, sigh, and melt; it could be given to God or cleaned out and inhabited by Christ. And so one might also imagine a heart “swimming in blood,” as the German poet Georg Christian Lehms wrote in his cantata libretto of 1711; a text set to music not only in 1714 by Bach but also two years before by his German contemporary Christoph Graupner, and subsequently heard by congregations in Weimar, Cöthen, Leipzig, and Darmstadt. Lehms’s poem draws on a long-standing Christian devotional tradition that conjoined hearts and bodily fluids, in visions of faithful hearts crying blood or sinners’ hearts drenched in waters of fear. But what was it like to be a body whose heart could undergo such procedures? What kind of physiology underpinned the veracity of these formulations? Simply casting them as poetic flights of fancy would mean disregarding the fundamentally embodied nature of such metaphors, which acquired their meaningfulness precisely through a more or less tangible link to a perceived corporeal reality. In heeding Gail Kern Paster’s call for an “interpretive literalism” in approaching early modern tropes based on bodily parts and functions, we might instead start from the assumption that experiences of seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century bodiliness were historically particular in such a way that they could give rise to this kind of imagery without too great a sense of rupture or alienation. If Lehms’s poetry strikes some present-day listeners as “repellent,” this response may exactly map out the distance to be traversed in order to recover those past modes of being-in-the-body that could produce and sustain such language.

Recuperating these historical forms of bodiliness has formed a key preoccupation of early modern scholarship at least since Thomas Csordas’s programmatic call in 1990 for a focus on “embodiment” in the study of human cultures, approaching the body less as a text to be deciphered than as the locus of lived experience. Of course, as Mark M. Smith has recently reminded us, any claims toward the recovery of a usable, consumable sensory past, potentially culminating in “lickable text, scratch-and-sniff pages, touch-and-feel pads” to convey an authentic historical experience to present-day readers, must be treated with extreme caution. My argument here, too, stays well clear of an attempt to recreate for current listeners any of those past corporeal habits of which a careful historical investigation might offer some glimpses; music already went through its own “authenticity” debate some decades ago, after all. Still, Bruce R. Smith’s invitation to “project ourselves into the historically reconstructed field of perception as far as we are able” can seem particularly intriguing in the case of music, since it not only encompasses the duality of presence and pastness in uniquely challenging ways but also ostensibly performs that effortless merger of sensation and meaning, both of which it produces in abundance, every time it sounds. Past musical practices and sound worlds in this sense offer an especially promising access point for a historical inquiry that aims to steer a course between the two extremes of positing the body either as pure presence or as mere representation.

In the early modern context, such an exercise in retro-projection initially requires a fundamental repositioning of the category of “body,” by which that post-Cartesian self- contained entity separate from the mind is refigured instead as “body-mind,” or, in Susan James’s terminology, “body-soul composite.” The wealth of physiological and psychological processes that constituted these body-souls comes into sharp focus when setting out to reconstruct the ways in which music acted upon or within them. Since the historical record is frustratingly slim with regard to actual flesh-and-blood listeners caught in the act, their experiences of engaging with music (in particular in the context of a worship service) are pieced together here from a range of theological, scientific, and musical sources chosen for their proximity to the German Lutheran milieu inhabited by Bach. If, as Daniel Chua has observed, by the middle of the eighteenth century music would by and large come to be understood as only that which is heard, it is this later reduction to the acoustic that needs to be reversed (unthought and unfelt) in order to recapture how music’s sounding materials reverberated not only through “throats, mouths, lungs, ears, and heads” but also through hearts, guts, and limbs, as well as spirits and souls. Although the study of music as a performed, sounding activity has recently become something of a new orthodoxy within musicology, and this focus on performance has made the bodies behind (or, rather, in) music more immediately tangible, those bodies are still in need of much more nuanced historicization. Like James Q. Davies in his recent study of nineteenth-century virtuosity, I suggest that acts of musicking, in their capacity not just to reflect but to generate particular modes of inhabiting the body, offer a hitherto underused resource in coming to grips with the animate bodies of the past. What I envisage, then, is a kind of somatic archaeology that pushes Elizabeth Le Guin’s proposal of a “carnal musicology” to a new level of fleshliness. Such an approach might thereby begin to address that “huge gap in early modern sensory history” to which Penelope Gouk has recently alerted us, moving toward a radically revised, somatic ontology of early modern music making. Continue reading …

This essay proposes a somatic archaeology of German Lutheran music making around 1700. Focusing on a single cantata by Johann Sebastian Bach, it sets out to reconstruct the capacities of early modern body-souls for musical reverberation, affective contagion, and spiritual transformation.

BETTINA VARWIG is Lecturer in Music and Fellow of Emmanuel College at the University of Cambridge. She is the author of Histories of Heinrich Schütz (Cambridge University Press, 2011) and is currently working on a book project entitled An Early Modern Musical Physiology.

BETTINA VARWIG is Lecturer in Music and Fellow of Emmanuel College at the University of Cambridge. She is the author of Histories of Heinrich Schütz (Cambridge University Press, 2011) and is currently working on a book project entitled An Early Modern Musical Physiology.

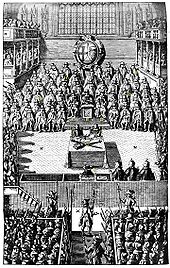

On the morning of January 9, 1649, Sergeant-at-Arms Edward Dendy rode into Westminster Hall, surrounded by an entourage of officers and followed by six trumpeters on horseback, with more than two hundred Horse and Foot Guards behind them. Drums beat in the Old Palace Yard, the trumpeters sounded their horns in the hall, and the crier announced the “erecting of an High Court of Justice, for the trying and judging of Charles Stuart King of England.” Eleven days later, the two great gothic doors opened to a space transformed. The trial’s managers had torn out the hall’s ramshackle barriers and the booksellers’ and milliners’ booths that lined its walls and constructed a central raised stage flanked by galleried boxes, whose decorative columns supported balconies fronted by ornately carved balustrades. They had spread Turkish carpets on the tables and platforms and hung yards and yards of scarlet draperies from the elevated seating at the back of the stage. And they had built, at the center, a three-tiered dais with a trio of armchairs, the furniture adorned in gold-fringed, tasseled crimson velvet and studded with precious metals. Into this magnificently appointed space marched several hundred guards bearing brilliantly gilded “rich partizans” and “javelins” decorated “with velvet and fringe.” With them was the sergeant-at-arms, holding aloft the great golden mace of the House of Commons, and behind him a sword bearer carrying the Sword of State brought from the Westminster Jewel Tower. Those in charge had issued an order: even outside the precincts of the court, the presiding judge was to be referred to only by his new title: “Lord President of the High Court of Justice.” As the sixty-seven commissioners serving as judges ascended to their scarlet-draped seats, the “Lord . . . of the High Court,” in a “black Tufted Gown” with an inordinately long train (carried by an entourage of attendants), paraded toward his dais amidst the sea of begilded and velvet-fringed javelins. This was hardly the austere mise-en-scène one might expect from the “godly Puritans” who had mounted their coup d’état and put their king on trial—in part, at least, in the name of stamping out ceremonial idolatry and the gaudy pomp of the vainglorious Stuarts.

On the morning of January 9, 1649, Sergeant-at-Arms Edward Dendy rode into Westminster Hall, surrounded by an entourage of officers and followed by six trumpeters on horseback, with more than two hundred Horse and Foot Guards behind them. Drums beat in the Old Palace Yard, the trumpeters sounded their horns in the hall, and the crier announced the “erecting of an High Court of Justice, for the trying and judging of Charles Stuart King of England.” Eleven days later, the two great gothic doors opened to a space transformed. The trial’s managers had torn out the hall’s ramshackle barriers and the booksellers’ and milliners’ booths that lined its walls and constructed a central raised stage flanked by galleried boxes, whose decorative columns supported balconies fronted by ornately carved balustrades. They had spread Turkish carpets on the tables and platforms and hung yards and yards of scarlet draperies from the elevated seating at the back of the stage. And they had built, at the center, a three-tiered dais with a trio of armchairs, the furniture adorned in gold-fringed, tasseled crimson velvet and studded with precious metals. Into this magnificently appointed space marched several hundred guards bearing brilliantly gilded “rich partizans” and “javelins” decorated “with velvet and fringe.” With them was the sergeant-at-arms, holding aloft the great golden mace of the House of Commons, and behind him a sword bearer carrying the Sword of State brought from the Westminster Jewel Tower. Those in charge had issued an order: even outside the precincts of the court, the presiding judge was to be referred to only by his new title: “Lord President of the High Court of Justice.” As the sixty-seven commissioners serving as judges ascended to their scarlet-draped seats, the “Lord . . . of the High Court,” in a “black Tufted Gown” with an inordinately long train (carried by an entourage of attendants), paraded toward his dais amidst the sea of begilded and velvet-fringed javelins. This was hardly the austere mise-en-scène one might expect from the “godly Puritans” who had mounted their coup d’état and put their king on trial—in part, at least, in the name of stamping out ceremonial idolatry and the gaudy pomp of the vainglorious Stuarts.

The Los Angeles Review of Books called Compass a “brilliant, elusive, outré love letter to Middle Eastern art and culture.” We’re reading it now to confirm.

The Los Angeles Review of Books called Compass a “brilliant, elusive, outré love letter to Middle Eastern art and culture.” We’re reading it now to confirm.

“This isn’t right.” Almost as soon as the man resembling Martin Luther King Jr. has begun to speak, he interrupts himself in frustration. “I accept this honor,” he’d been saying, “for our lost ones, whose deaths pave our path, and for the twenty million Negro men and women motivated by dignity and a disdain for hopelessness.” What does he think isn’t right? Is it the racial oppression he has been evoking? Or is it the felt inadequacy of his words to that injustice? As the man turns away from us, we find that he has been speaking into a mirror, and that he is frustrated in the immediate context by his efforts at getting dressed . “Corrie”—it is King, we now understand, and he’s not alone; his wife Coretta is with him—“this ain’t right.” “What’s that?” she asks, entering from another room. “This necktie. It’s not right.” “It’s not a necktie,” she corrects him, “it’s an ascot.” “Yeah, but generally, the same principles should apply, shouldn’t they? It’s not right.”

“This isn’t right.” Almost as soon as the man resembling Martin Luther King Jr. has begun to speak, he interrupts himself in frustration. “I accept this honor,” he’d been saying, “for our lost ones, whose deaths pave our path, and for the twenty million Negro men and women motivated by dignity and a disdain for hopelessness.” What does he think isn’t right? Is it the racial oppression he has been evoking? Or is it the felt inadequacy of his words to that injustice? As the man turns away from us, we find that he has been speaking into a mirror, and that he is frustrated in the immediate context by his efforts at getting dressed . “Corrie”—it is King, we now understand, and he’s not alone; his wife Coretta is with him—“this ain’t right.” “What’s that?” she asks, entering from another room. “This necktie. It’s not right.” “It’s not a necktie,” she corrects him, “it’s an ascot.” “Yeah, but generally, the same principles should apply, shouldn’t they? It’s not right.” “This is where we should go on vacation—in winter. What snow, light, mountains!” These lines were written by Aleksandr Rodchenko to his wife, Varvara Stepanova, from the White Sea-Baltic Canal, which was then being constructed by prisoners at an eponymous forced labor camp, one of the Soviet Union’s first, where more than twenty-five thousand—and possibly as many as fifty thousand—inmates lost their lives from 1931 to 1933. Had the photographer not yet seen the atrocities of the camp? Was he highlighting holiday pleasures in case his letter was read by someone other than its intended recipient? Rodchenko’s pronouncement is so utterly damning in its willful ignorance of the human toll of the construction of the canal as to render any possible justifications moot. This description of a gulag—bracketed, to top it off, with declarations that the sun and the air are “wonderful”—effectively bars any interpretive engagement. One’s only recourse, it seems, is to denounce Rodchenko’s deliberate blindness to the grim efficiencies of the state machine.

“This is where we should go on vacation—in winter. What snow, light, mountains!” These lines were written by Aleksandr Rodchenko to his wife, Varvara Stepanova, from the White Sea-Baltic Canal, which was then being constructed by prisoners at an eponymous forced labor camp, one of the Soviet Union’s first, where more than twenty-five thousand—and possibly as many as fifty thousand—inmates lost their lives from 1931 to 1933. Had the photographer not yet seen the atrocities of the camp? Was he highlighting holiday pleasures in case his letter was read by someone other than its intended recipient? Rodchenko’s pronouncement is so utterly damning in its willful ignorance of the human toll of the construction of the canal as to render any possible justifications moot. This description of a gulag—bracketed, to top it off, with declarations that the sun and the air are “wonderful”—effectively bars any interpretive engagement. One’s only recourse, it seems, is to denounce Rodchenko’s deliberate blindness to the grim efficiencies of the state machine. AGLAYA GLEBOVA

AGLAYA GLEBOVA Inventing counterfactual histories is a common pastime of modern day historians, both amateur and professional. We speculate about an America ruled by Jefferson Davis, a Europe that never threw off Hitler, or a second term for JFK. These narratives are often written off as politically inspired fantasy or as pop culture fodder, but in Telling It Like It Wasn’t, Catherine Gallagher takes the history of counterfactual history seriously, pinning it down as an object of dispassionate study. She doesn’t take a moral or normative stand on the practice, but focuses her attention on how it works and to what ends—a quest that takes readers on a fascinating tour of literary and historical criticism.

Inventing counterfactual histories is a common pastime of modern day historians, both amateur and professional. We speculate about an America ruled by Jefferson Davis, a Europe that never threw off Hitler, or a second term for JFK. These narratives are often written off as politically inspired fantasy or as pop culture fodder, but in Telling It Like It Wasn’t, Catherine Gallagher takes the history of counterfactual history seriously, pinning it down as an object of dispassionate study. She doesn’t take a moral or normative stand on the practice, but focuses her attention on how it works and to what ends—a quest that takes readers on a fascinating tour of literary and historical criticism. Catherine Gallagher

Catherine Gallagher One curious feature of nineteenth-century British and American novels about Jesus is the fact that their central figure often remains largely offstage. In Harriet Martineau’s Traditions of Palestine (1830), William Ware’s Julian; or, Scenes in Judea (1841), Edwin A. Abbott’s Philochristus: Memoirs of a Disciple of the Lord (1878), Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880), James Freeman Clarke’s The Legend of Thomas Didymus: The Jewish Skeptic (1881), Marie Corelli’s Barabbas (1893), and Florence Morse Kingsley’s Titus, a Comrade of the Cross (1894), Jesus is pushed into the background while the narrative follows the life of a minor historical figure or the cultural milieu of first-century Palestine. Ware builds an elaborate character system out of various bit players from the canonical Gospels, turning Barabbas, the robber who is pardoned unwittingly in Jesus’s place, into Mary Magdalene’s ne’er-do-well brother and a proxy for her own narrative arc. Kingsley, beating Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) to the punch, forges a comic subplot out of the story of a cripple whom Jesus robs of employment: “Ha, fellow! thou didst heal me, three years ago, of the palsy, which had withered my limbs; and in so doing took away my living, for my begging no longer brought me money.” And behind all of this are elaborate historical backdrops drawn from both secular historiography and Holy Land tourist guidebooks.

One curious feature of nineteenth-century British and American novels about Jesus is the fact that their central figure often remains largely offstage. In Harriet Martineau’s Traditions of Palestine (1830), William Ware’s Julian; or, Scenes in Judea (1841), Edwin A. Abbott’s Philochristus: Memoirs of a Disciple of the Lord (1878), Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880), James Freeman Clarke’s The Legend of Thomas Didymus: The Jewish Skeptic (1881), Marie Corelli’s Barabbas (1893), and Florence Morse Kingsley’s Titus, a Comrade of the Cross (1894), Jesus is pushed into the background while the narrative follows the life of a minor historical figure or the cultural milieu of first-century Palestine. Ware builds an elaborate character system out of various bit players from the canonical Gospels, turning Barabbas, the robber who is pardoned unwittingly in Jesus’s place, into Mary Magdalene’s ne’er-do-well brother and a proxy for her own narrative arc. Kingsley, beating Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) to the punch, forges a comic subplot out of the story of a cripple whom Jesus robs of employment: “Ha, fellow! thou didst heal me, three years ago, of the palsy, which had withered my limbs; and in so doing took away my living, for my begging no longer brought me money.” And behind all of this are elaborate historical backdrops drawn from both secular historiography and Holy Land tourist guidebooks. SEBASTIAN LECOURT

SEBASTIAN LECOURT