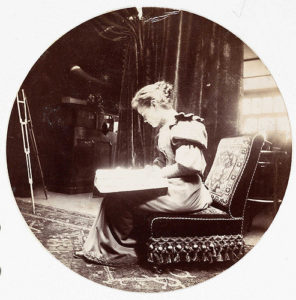

Reading for Mood

by Jonathan Flatley

The essay begins:

We all know that we have feelings when we encounter works of art. We laugh, we cry. We feel pity and fear. We like and we dislike. We shudder and shiver and tingle. We are amused, delighted, thrilled, teary, bored, relaxed, turned on, horrified, enraged, surprised, depressed, embarrassed, shocked, and fascinated. We know that these “aesthetic” feelings constitute one of the primary values of art as such, and that the problem of how to analyze and evaluate these feelings is one of the basic problems of aesthetic theory, at least since Plato worried about the way poets affected their audiences in The Republic. Many of our fundamental aesthetic categories—tragedy and comedy, the beautiful and the sublime—have become fundamental because they offer ways to think about how art affects its audiences.

We all know that we have feelings when we encounter works of art. We laugh, we cry. We feel pity and fear. We like and we dislike. We shudder and shiver and tingle. We are amused, delighted, thrilled, teary, bored, relaxed, turned on, horrified, enraged, surprised, depressed, embarrassed, shocked, and fascinated. We know that these “aesthetic” feelings constitute one of the primary values of art as such, and that the problem of how to analyze and evaluate these feelings is one of the basic problems of aesthetic theory, at least since Plato worried about the way poets affected their audiences in The Republic. Many of our fundamental aesthetic categories—tragedy and comedy, the beautiful and the sublime—have become fundamental because they offer ways to think about how art affects its audiences.

Yet it is not always clear how to translate the insights from this theoretical tradition into the reading of specific works of art or literature. It can be hard to shake the sense that the discussion of “how art makes us feel” is necessarily subjective or anecdotal. Doesn’t the affective response produced by a given text depend on the reader and the reader’s particular situation? Don’t observations about aesthetic experience say more about the reader or viewer than the work? This, of course, is the concern voiced in W. K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley’s essay on the “Affective Fallacy,” where they warn that evaluating a poem in terms of the feelings it produces “is a confusion between the poem and its results (what it is and what it does).” Such a project, they write, “begins by trying to derive the standard of criticism from the psychological effects of the poem and ends in impressionism and relativism.” As a result, “the poem itself, as an object of specifically critical judgment, tends to disappear.” Even if critics are no longer as compelled as they once were by the New Critical devotion to the poem as an autonomous “verbal icon,” doubts remain about how critics can or should account for the particular affective or emotional impact of a given text on the readers who encounter it. The suspicion of “impressionism and relativism” lingers. At best, mustn’t such a claim be a specific sociological account of a particular audience and a particular situated encounter? Don’t we risk universalizing our own subjective responses when we try to talk about the aesthetic experience of a particular work? Continue reading …

Beginning with a consideration of the distinct places of affect in aesthetic theory and in critical reading practices, this essay makes a case for mood as a critical concept that helps us to read for the historicity and potentially political effects of aesthetic practices.

Walter Benn Michaels has responded to the essay in his January 1, 2018, post at nonsite.org: Grimstad on Experience, Flatley on Affect.

JONATHAN FLATLEY is Professor in the English Department at Wayne State University, where he was the editor of Criticism: A Quarterly for Literature and the Arts from 2007 to 2012. He is the author of Affective Mapping: Melancholia and the Politics of Modernism (Harvard, 2008) and Like Andy Warhol (University of Chicago, Fall 2017).

JONATHAN FLATLEY is Professor in the English Department at Wayne State University, where he was the editor of Criticism: A Quarterly for Literature and the Arts from 2007 to 2012. He is the author of Affective Mapping: Melancholia and the Politics of Modernism (Harvard, 2008) and Like Andy Warhol (University of Chicago, Fall 2017).