Mimesis on Trial: Legal and Literary Verisimilitude in Boccaccio’s Decameron

by Justin Steinberg

The essay begins:

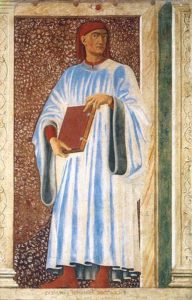

Boccaccio is generally the least appreciated of the “Three Crowns” of the Italian literary canon (after Petrarch and Dante), yet his focus on the realistic, even gritty details of everyday life, everyday characters, and everyday language has no real precedent, at least not one of the scope of the Decameron. Studies of the novel typically identify Boccaccio’s masterpiece as an influential precursor in the development of modern literary realism, and Erich Auerbach devotes a critical chapter to the Decameron in his monumental history of Western mimesis. Although recent scholarship has called into question Boccaccio’s supposed modernity, underlining the allegorical aspects of the Decameron and its continued debt to medieval textual practices, it is difficult to deny that, at the very least, Boccaccio expands the frame of what can be legitimately represented in literature.

Boccaccio is generally the least appreciated of the “Three Crowns” of the Italian literary canon (after Petrarch and Dante), yet his focus on the realistic, even gritty details of everyday life, everyday characters, and everyday language has no real precedent, at least not one of the scope of the Decameron. Studies of the novel typically identify Boccaccio’s masterpiece as an influential precursor in the development of modern literary realism, and Erich Auerbach devotes a critical chapter to the Decameron in his monumental history of Western mimesis. Although recent scholarship has called into question Boccaccio’s supposed modernity, underlining the allegorical aspects of the Decameron and its continued debt to medieval textual practices, it is difficult to deny that, at the very least, Boccaccio expands the frame of what can be legitimately represented in literature.

At the same time, something is inevitably lost when we view the Decameron from the end point of the modern novel. Our retrospective glance privileges a very specific conception of realism, a conception defined by its rejection of rhetorical notions of appropriateness and fittingness. (This unruly literary style befits a genre “in which one can tell absolutely any story in any way whatsoever.”) Auerbach, for example, maintains that only once literature has freed itself from the rigid confines of classical decorum is it possible for authors to depict the world in its complex, particularistic entirety. Yet this version of realism does not admit the extent to which Boccaccio’s mimetic art remains preoccupied by rhetorical verisimilitude. While it’s true that Boccaccio incessantly interrogates the status of verisimilitude throughout the Decameron—what it means for something to “fit” in a given scenario—he does so by delving into the precise components of the circumstantiae (the who, what, where, when, why, and how of a case, deployed by an orator to enhance the “true-seemingness” of his argument). Even when exploring its inner contradictions, that is, Boccaccio innovates through, rather than from, rhetoric. Studies that neglect the influence of rhetorical verisimilitude on Boccaccio’s realism, preferring to imagine a seamless evolution from the plausible to the particular, miss this essential tension at the heart of the Decameron between competing notions of the real.

Rather than treating the Decameron as a stepping-stone on the path toward modern realism, I will argue that Boccaccio’s realistic style is a historically specific response to a historically specific crisis of verisimilitude. This crisis was propelled by a critical institutional innovation: the rise and spread of the medieval inquisitorial procedure. In the inquisitorial trial, judges were frequently called upon to estimate the likelihood of circumstantial evidence; this migration of notions about the probable from the rhetorical to the judicial sphere, from persuasion to evidence, is Boccaccio’s primary focus and concern. Through the many trial scenes in the Decameron, he illustrates the dangers that arise when judges, witnesses, and prosecutors are “trapped by a picture”—when the theater of justice becomes a self-fulfilling mimesis of the already known and always seen. The singular, remarkable details that eventually come to the fore in these trials (and that characterize the plot lines of Boccaccio’s novelle) reveal the disconnect between norms of likelihood and the particulars of a case.

Not only do the trials in the Decameron probe the legal uses of verisimilitude as evidence, they also raise questions about verisimilitude as a literary device. What is the relationship between an aesthetic principle of “fittingness” and the normative knowledge of “what happens for the most part”? What is the role of innovation in an art of the probable? How can a plausible account of the facts encompass historical contingency and singularity? These simultaneously legal and literary questions are exactly what the Decameron is wired to navigate: the degree to which the verisimilar picture must be open to the singular case, the structure open to the event.

My argument, then, is not simply that Boccaccio was influenced by rhetorical verisimilitude but also that he employs the numerous “procedural” tales in the Decameron to reflect critically on the nature of, and the increasing real-world power of, realistic narrative. Continually questioning the very realism he employs as a poet, he puts mimesis on trial. Continue reading …

In this essay Justin Steinberg argues that the celebrated realism of Boccaccio’s Decameron responds to the new prominence of verisimilitude in legal contexts in his time.

Justin Steinberg is Professor of Italian literature at the University of Chicago and editor-in-chief of Dante Studies. He is the author of Accounting for Dante: Urban Readers and Writers in Late Medieval Italy (Notre Dame, 2007) and Dante and the Limits of the Law (Chicago, 2015). He is currently writing a book on Boccaccio, representation, and the law.