The essay begins:

In a 1962 letter to the conservative Relm Foundation, Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992) discussed plans for disseminating his brand of neoliberalism in Japan. Hayek would win the Nobel Prize for economics in 1974, and by then he had long since established himself as one of the most influential neoliberal thinkers of the Cold War years. In the letter, he discussed a “deliberate campaign” that would bring “libertarian scholars” to Japan, and that would culminate in a Tokyo meeting of the neoliberal network he led, the Mont Pèlerin Society. Hayek emphasized that “there seems now to be a receptive atmosphere for libertarian ideas in Japan, and if this is true the effects of some well directed efforts may be of crucial importance with this volatile people.” Hoping to capitalize on this “receptive atmosphere,” he also arranged for his recent book, The Constitution of Liberty (1960), to be translated into Japanese by Paul Nishiyama, one of his graduate advisees on the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago. Hayek would visit Japan four times between 1964 and 1971, and he once wrote that these were “immensely enjoyable” visits that had led his wife to “[take] up the study of Japanese.”

Today, Hayek’s ideas are part of larger dialogues in Japan, the United States, and elsewhere about the culture and politics of neoliberalism. These discussions have only become more urgent in the years since the global economic collapse of 2008. In particular, the question of whether neoliberal reason is the cause or the cure of our current economic and social strife has recently attracted the attention of scholars in fields ranging from political science and economics to history and anthropology. This essay aims to contribute to these discussions by thinking through the cultural dynamics of neoliberal reason from the perspective of modern Japanese literature.

My analysis is premised on a concrete connection between the seemingly disparate fields of modern Japanese literature and Hayekian neoliberalism: In 1957, the most famous novel of modern Japan, Kokoro (1914) by Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916), was translated into English by Edwin McClellan (1925–2009), who was at the time one of Hayek’s advisees on the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago. McClellan was born in Japan to a Japanese mother and a Scottish father, and he counted both Japanese and English as native languages. The novel he translated while working with Hayek, Kokoro, is a literary masterpiece that centers on the relationship between an alienated university student and an older man, known only as “Sensei” (my teacher), who shares his thoughts on the loneliness of the modern world with the student before committing suicide just after the death of the Meiji Emperor in 1912.

My analysis is premised on a concrete connection between the seemingly disparate fields of modern Japanese literature and Hayekian neoliberalism: In 1957, the most famous novel of modern Japan, Kokoro (1914) by Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916), was translated into English by Edwin McClellan (1925–2009), who was at the time one of Hayek’s advisees on the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago. McClellan was born in Japan to a Japanese mother and a Scottish father, and he counted both Japanese and English as native languages. The novel he translated while working with Hayek, Kokoro, is a literary masterpiece that centers on the relationship between an alienated university student and an older man, known only as “Sensei” (my teacher), who shares his thoughts on the loneliness of the modern world with the student before committing suicide just after the death of the Meiji Emperor in 1912.

McClellan’s translation of Kokoro deeply moved Hayek. In fact, McClellan’s literary rendering of Sōseki’s poetic prose so powerfully affected Hayek that he later hired McClellan to polish the language of his own writings, including such classics of neoliberal thought as The Constitution of Liberty and Law, Legislation and Liberty (3 volumes; published in 1973, 1976, and 1979). While moonlighting as an editor (of sorts) for Hayek, McClellan was better known as an influential professor of Japanese literature at Chicago and, later, Yale. During this time, his translation of Kokoro was probably the most widely assigned novel in courses on modern Japan taught in America. The prominence of the translation, though, can make us forget that it was actually undertaken at a time when the field of Japan studies in American academe did not yet exist, and by a graduate student who was trained by scholars who knew almost nothing about Japan.

In the 1950s, after all, McClellan was studying with social scientists, philosophers, and economists affiliated with the Committee on Social Thought at Chicago—not Japanologists. In a 1956 letter of recommendation, in fact, Hayek described McClellan as a political scientist: “[McClellan] is an unusually cultivated man of wide interests and is now employing his good background in economic and political science for a study of certain very important intellectual trends in Japan—an aspect of the influence of Western ideas on the political developments in that country.” McClellan’s translation of Kokoro would go on to become standard reading for generations of students interested in modern Japan, but the point of departure for my own analysis is that it was originally composed and received within the context of a nascent neoliberal movement led by his advisor, Hayek.

This essay focuses on the possibility that intellectuals in 1950s America who knew little about Japan may have found in McClellan’s translation of Kokoro a literary rendering of the neoliberal sensibilities that they were then conceptualizing in expository texts of their own. I begin by examining McClellan’s contacts at Chicago in the 1950s and limn his position within a circle of neoliberal thinkers who became the first readers of his Kokoro translation. I then read the translation itself in the context of the neoliberal conviction that “great books” and other expressions of bourgeois culture reveal the universality of the human condition. I pay particular attention to how the translation might have engaged the antihistoricst sensibilities of McClellan’s Chicago contacts in passages where he scrubbed Sōseki’s language of its cultural specificity, and in passages where the formal qualities of the narrative itself distribute readerly sensibility in the direction of a timeless humanism beyond the boundaries of cultural and historical particularity. These analyses lead me to conclude that McClellan’s translation supplied a way of feeling the ambience and atmosphere of neoliberal reason without ever invoking the sign of “neoliberalism” per se. For in moments when Sōseki’s translated prose led readers to forget the name of the neoliberal ideas that it allowed them to feel, the aesthetic atmosphere of McClellan’s Kokoro itself became, as it were, all the names of neoliberalism. Continue reading …

As a graduate student at the University of Chicago in the mid-1950s, Edwin McClellan (1925–2009) translated into English the most famous novel of modern Japan, Kokoro (1914), by Natsume Sōseki. This essay tells the story of how the translation emerged from and appealed to a nascent neoliberal movement that was led by Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992), the Austrian economist who had been McClellan’s dissertation advisor.

BRIAN HURLEY will be joining the faculty of Syracuse University in the fall as an Assistant Professor of Japanese literature, film, and culture. His research has also appeared in the Journal of Japanese Studies and in the Japanese-language journal of literary criticism Bungaku. He is currently working on a book manuscript that examines the confluences of literature and thought in modern Japan.

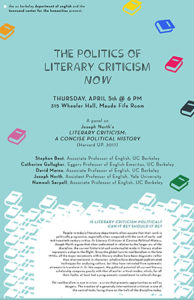

People in today’s literature departments often assume that their work is politically progressive, especially when compared with the work of early- and mid-twentieth-century critics. In Literary Criticism: A Concise Political History, Joseph North argues that when understood in relation to the longer arc of the discipline, the current historicist and contextualist mode in literary studies represents a step lo the Right. Since the global turn to neoliberalism in the late 1970s, all the major movements within literary studies have been diagnostic rather than interventionist in character; scholars have developed sophisticated techniques for analyzing culture, but they have retreated from systematic attempts to transform it. In this respect, the political potential of current literary scholarship compares poorly with that of earlier critical modes, which, for all their faults, at least had a programmatic commitment to cultural change. Yet neoliberalism is now in crisis – a crisis that presents opportunities as well as dangers. The creation of a genuinely interventionist criticism is one of the central tasks facing those on the Left of the discipline today.

People in today’s literature departments often assume that their work is politically progressive, especially when compared with the work of early- and mid-twentieth-century critics. In Literary Criticism: A Concise Political History, Joseph North argues that when understood in relation to the longer arc of the discipline, the current historicist and contextualist mode in literary studies represents a step lo the Right. Since the global turn to neoliberalism in the late 1970s, all the major movements within literary studies have been diagnostic rather than interventionist in character; scholars have developed sophisticated techniques for analyzing culture, but they have retreated from systematic attempts to transform it. In this respect, the political potential of current literary scholarship compares poorly with that of earlier critical modes, which, for all their faults, at least had a programmatic commitment to cultural change. Yet neoliberalism is now in crisis – a crisis that presents opportunities as well as dangers. The creation of a genuinely interventionist criticism is one of the central tasks facing those on the Left of the discipline today.

My analysis is premised on a concrete connection between the seemingly disparate fields of modern Japanese literature and Hayekian neoliberalism: In 1957, the most famous novel of modern Japan, Kokoro (1914) by Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916), was translated into English by Edwin McClellan (1925–2009), who was at the time one of Hayek’s advisees on the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago. McClellan was born in Japan to a Japanese mother and a Scottish father, and he counted both Japanese and English as native languages. The novel he translated while working with Hayek, Kokoro, is a literary masterpiece that centers on the relationship between an alienated university student and an older man, known only as “Sensei” (my teacher), who shares his thoughts on the loneliness of the modern world with the student before committing suicide just after the death of the Meiji Emperor in 1912.

My analysis is premised on a concrete connection between the seemingly disparate fields of modern Japanese literature and Hayekian neoliberalism: In 1957, the most famous novel of modern Japan, Kokoro (1914) by Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916), was translated into English by Edwin McClellan (1925–2009), who was at the time one of Hayek’s advisees on the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago. McClellan was born in Japan to a Japanese mother and a Scottish father, and he counted both Japanese and English as native languages. The novel he translated while working with Hayek, Kokoro, is a literary masterpiece that centers on the relationship between an alienated university student and an older man, known only as “Sensei” (my teacher), who shares his thoughts on the loneliness of the modern world with the student before committing suicide just after the death of the Meiji Emperor in 1912.