Absolutely Modern: Dylan, Rimbaud, and Visionary Song

by Timothy Hampton

The essay begins:

In December of 1965, Bob Dylan gave a news conference in San Francisco. Following his rise to fame in the early 1960s as a writer of politically themed “folk” songs, Dylan had caused a stir several months earlier at the Newport Folk Festival by appearing on stage in a black leather jacket, accompanied by an electric blues band. Now he was beginning an extensive tour to play a new kind of music—music that he described in his press conference as neither folk, nor rock, nor folk-rock, but something called “vision music.” In this essay I want to consider what that phrase might mean.

In what follows I will argue that Dylan’s famous turn to “electric music” is part of a larger stylistic shift in his approach to writing and performing—a shift that unfolds across the middle years of the 1960s. Imagery, lyric form, musical structure, and even the dynamics of performance are recalibrated through new strategies that emerge to replace the earlier interest in topical songs. This is what I will call a “visionary poetics.” It places Dylan in a tradition of visionary poetry reaching back as far as Dante. However, as I will show, Dylan’s development during this period takes shape through his dialogue with literary modernism. For mid-1960s Dylan, the visionary is the modern. My focus will be, principally, on the trio of great “electric” albums produced in the mid-’60s: Bringing It All Back Home (1964), Highway 61 Revisited (1965), and Blonde on Blonde (1966). What interests me is less the notion of “poetic inspiration” (often assumed to be part of some generational Zeitgeist) than the development of the specific literary techniques and musical innovations through which Dylan expands his songwriting range. I will trace the ways in which the expansion of his songwriting palette during this period generates a set of aesthetic and ethical problems that place pressure on the forms of popular song.

In what follows I will argue that Dylan’s famous turn to “electric music” is part of a larger stylistic shift in his approach to writing and performing—a shift that unfolds across the middle years of the 1960s. Imagery, lyric form, musical structure, and even the dynamics of performance are recalibrated through new strategies that emerge to replace the earlier interest in topical songs. This is what I will call a “visionary poetics.” It places Dylan in a tradition of visionary poetry reaching back as far as Dante. However, as I will show, Dylan’s development during this period takes shape through his dialogue with literary modernism. For mid-1960s Dylan, the visionary is the modern. My focus will be, principally, on the trio of great “electric” albums produced in the mid-’60s: Bringing It All Back Home (1964), Highway 61 Revisited (1965), and Blonde on Blonde (1966). What interests me is less the notion of “poetic inspiration” (often assumed to be part of some generational Zeitgeist) than the development of the specific literary techniques and musical innovations through which Dylan expands his songwriting range. I will trace the ways in which the expansion of his songwriting palette during this period generates a set of aesthetic and ethical problems that place pressure on the forms of popular song.

Certainly, Dylan’s expansion of his lyric range owes something to the work of the Beat Generation and, in particular, to Allen Ginsberg, who was seated prominently at the San Francisco news conference. It was no accident that the San Francisco visit included a pilgrimage to the beatnik mecca of City Lights Books, where Dylan was photographed in the alley behind the store with Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Michael McClure. This was the already aging royalty of the Beats, who had, in their own time, rejected the collective activism of the Old Left to pursue individual beatitude or “beatness.” Dylan was bringing Greenwich Village intellectualism to the epicenter of the emerging sensory-based West Coast counterculture, casting himself as the heir to an earlier visionary generation. Yet Ginsberg had been working in a visionary mode from his very first published poems. Dylan now had to make himself into a visionary; he had to develop a new poetic vocabulary and link it to the limited formal capacities of the popular song.

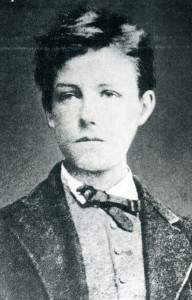

The touchstone for any study of visionary self-creation is neither Ginsberg, nor Ginsberg’s idol William Blake, but Arthur Rimbaud. It was Rimbaud who had given first voice to the brand of visionary modernism that Dylan would embrace. It was Rimbaud who had announced that the poet “makes himself into a visionary” (Illuminations, xxx). And it was Rimbaud who had codified, in his letters about poetry, the procedures and limitations of the visionary mode. My discussion here will set Dylan and Rimbaud in dialogue, less as a study of influence—though influence is part of the story—than one of affinity, using Rimbaud’s canonical accounts of visionary poetry as a template for tracing Dylan’s development. Continue reading …

The touchstone for any study of visionary self-creation is neither Ginsberg, nor Ginsberg’s idol William Blake, but Arthur Rimbaud. It was Rimbaud who had given first voice to the brand of visionary modernism that Dylan would embrace. It was Rimbaud who had announced that the poet “makes himself into a visionary” (Illuminations, xxx). And it was Rimbaud who had codified, in his letters about poetry, the procedures and limitations of the visionary mode. My discussion here will set Dylan and Rimbaud in dialogue, less as a study of influence—though influence is part of the story—than one of affinity, using Rimbaud’s canonical accounts of visionary poetry as a template for tracing Dylan’s development. Continue reading …

Bob Dylan’s turn from “folk music” to “electric music” in the 1960s involves the development of a new visionary poetics. Through a consideration of his affinity with the French Symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud, this essay traces Dylan’s recasting of himself as a visionary and studies the pressures placed by this process on lyric form, on poetic diction, and on the representation of the self in popular music.

TIMOTHY HAMPTON is Professor of Comparative Literature and Chair of French at the University of California, Berkeley. His most recent book is Fictions of Embassy: Literature and Diplomacy in Early Modern Europe (Cornell University Press, 2009). He is currently working on a study of the history of cheerfulness.