“A Hail of Information”: Ulysses, Topic Modeled

Hoyt Long and Richard Jean So, University of Chicago

What can a quantitative analysis of style tell us about James Joyce’s Ulysses? Quite a lot, according to Eric Bulson. In his “Ulysses by Numbers,” Bulson uses some of the simplest forms of “stylometrics”—word counts and measures of lexical diversity—to provide new insights into some fundamental questions: why do the novel’s episodes get longer? What’s the relationship between an episode’s length and its plot? Bulson productively correlates the concrete evidence given by word counts with questions of composition and the material constraints of serialization. While the straightforward empiricism of his argument is a strength, it left us to wonder what it misses by treating words as homogenous numerical units abstracted from their semantic contexts. But not because we believe numbers and counting are unsuited to an interpretation of the novel. One of Bulson’s great insights is that counting is hardly alien to the project of reading Ulysses, an insight encapsulated in an epigraph from Hugh Kenner (“‘Words’ are blocks delimited by spaces. So we can count them.”). For us, the question is how to push this counting further. Can we count the words in ways that do not elide their contextual signifying power? Kenner too was interested not just in the number of words on the page, but the likelihood of certain words appearing with others, in what he called “space-time block[s] of words.”[1]

As quantitative approaches to text analysis have evolved, they have similarly shifted from counting words to counting collocations of words, and even collocations of collocations. One popular innovation along these lines is probabilistic topic modeling, which we propose here as a method for exposing what Kenner calls Ulysses’s larger “verbal systems.”[2] What we discover in the process is in part obvious—that topic modeling as a method of counting is also constrained by its assumptions about words as numerical units and their relation to each other. Ulysses troubles these assumptions, which amount to a highly particular theory of information. Precisely because it does so, however, topic modeling the novel also reveals something of how the novel functions as its own form of literary information. If word counts help us understand Joyce as a “mechanical counter,” topic models help us understand him as a careful “arranger” of latent verbal structures.[3]

Topic modeling was developed over a decade ago by computer scientists hoping to aid in tasks like “information retrieval, document classification, and corpus exploration.” A major enhancement on prior methods of automated document comparison, it was intended to “discover the themes that run through” a large collection of texts without any advanced knowledge of the texts themselves.[4] While this unsupervised approach was initially applied to the exploration of scientific and news articles, literary scholars have been quick to adopt its most common implementation—which employs latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA)—to track the “migratory formulae” of literary history in thousands of novels; to explore patterns of discourse in critical literature or across multiple types of corpora; and even to find themes in highly figurative poetic language.[5]

What topic modeling is good at is identifying words that occur together in multiple places across multiple documents. It connects words that tend to appear in similar contexts while helpfully distinguishing between uses of words that have multiple meanings. These clusters of co-occurring words are the “topics” produced by the model. For instance, if a topic model were applied to a large corpus of scientific articles, it might find that “matter” and “energy” frequently appeared together in a subset of those articles. Considered alone, these words are ambiguous and would not help the human reader intuit what the articles are about. But the topic model also returns additional contextual clues—words like “particle” and “dark”—thus allowing us to say that these articles probably have something to do with physics, as opposed to energy policy.

This idea that coherent topics like “physics” are latent within clusters of co-occurring words naturally relies on a set of ontological assumptions about what a topic is, but also what a document (or “text”) is and how it is generated. Topic modeling operates on the assumption that it can use the words it observes in documents to infer the “hidden structure” of topics that likely generated those documents.[6] Thus it assumes that there are topics that already exist in the world, like “physics,” and that individual words, such as “neutron,” are probabilistically associated with these topics. It then treats every document as if it were composed from some proportion of these topics, with the words in each topic more or less likely to be chosen based on their statistical distribution within that topic. So, for example, the model will say that a document contains a 50 per cent share of a topic because it contains lots of words frequently associated with that topic, like matter, energy, particle, and neutron. Based on these words, we could then infer that this document most likely has something to do with “physics,” even if it also contains smaller shares of other topics. The topic model essentially reverse engineers the process of composition based on the set of documents it is given, returning three things: lists of words for every topic it infers; the probability of those words being associated with that topic; and the proportion (or share) of a topic present in every document.

If there is any quantitative method that can relate the “blocks of words” in Ulysses to some larger verbal system, topic modeling would seem to be it. Imagine segmenting the novel into hundreds of smaller blocks—about 500 words each—and building an algorithm that infers a hidden structure of 60 topics from these blocks, which here represent our set of “documents” or “articles.” The assumption here would be that each block is composed from a subset of these 60 topics, and that words appeared in the block based on an existing association with those topics (and the words likely to appear within them). On the one hand, this is a preposterous way to consider how Ulysses was written. Surely Joyce did not draw on a limited set of topics as he wrote. And surely he did not write with fixed associations about which words were more likely to belong to which topic. By any measure, Ulysses is a “hail of information”—a spigot of words in which information itself takes precedence over narrative. Yet it is difficult to imagine this information being arranged as coherently as topic modeling would assume. That said, and as critics have long argued, the novel clearly possesses some kind of “hidden plan.”[7]

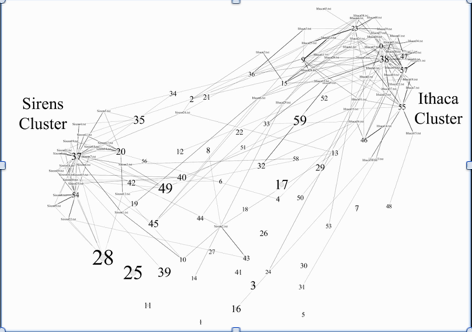

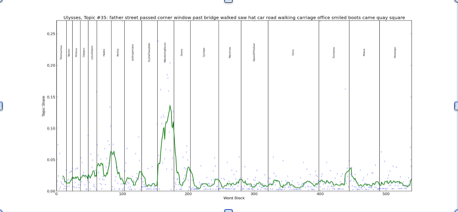

Indeed, when we ran a topic model on Ulysses, we saw that there was a latent structure in the patterns of co-occurring words, but that this structure was meaningful only to the extent it warped the core assumptions of LDA. For instance, we found that of the 539 total word blocks in the novel, less than a fifth had more than a 20 per cent share of any one topic. Instead, most contained a small share of many different topics, suggesting a lack of topic consistency within each block. This means that Ulysses has difficulty sticking with any single topic. If we look at the top five topics in each block, things get even more interesting. What we find is that the model identifies topics that cohere at the level of each canonical episode, even after we have excluded grammatical function words and character names.[8] All the blocks from “Sirens” and “Ithaca,” for example, huddle around a limited number of topics (Figure 1), meaning that they more or less draw on similar clusters of words. This visualization confirms what we already know from literary scholarship: that Ulysses is generally organized by “episodes,” each possessing its own loosely coherent form of language, style, and theme. In a sense, the topic modeling algorithm replicates the work that scholars such as Stuart Gilbert and Frank Budgen have done in revealing the novel as constituted by discrete “episodes,” thus making Ulysses’s overall “schema” relatively comprehensible to the reader.[9]

Figure 1. One way to visualize the relation of our “blocks of words” to the 60 inferred topics is to create a network diagram. In this case, we began with a network that linked all 539 text blocks to their five most prevalent topics (numbered). We then filtered out all blocks except for those in the “Sirens” and “Ithaca” episodes to show how little overlap there is in their highest ranked topics. The complete network of blocks and topics, along with a list of all 60 topics and their highest ranking words, is available at our website: chicagotextlab.uchicago.edu.

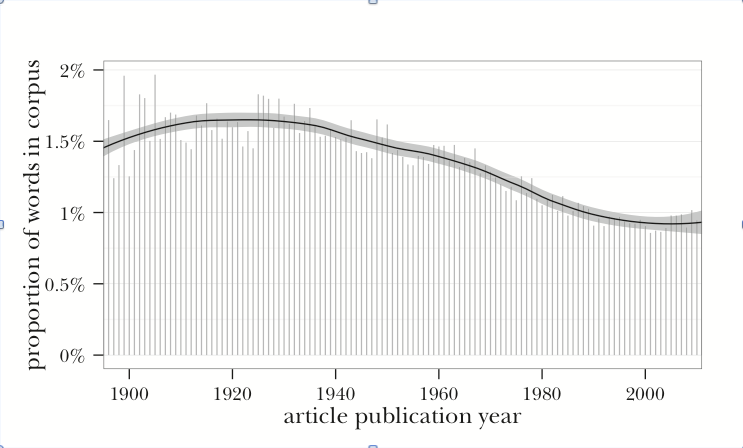

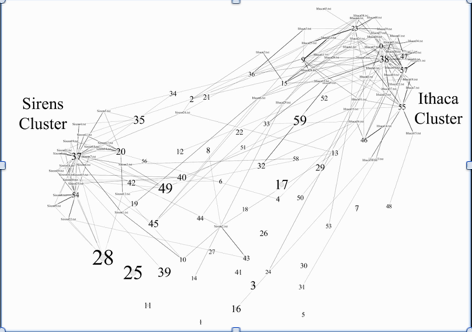

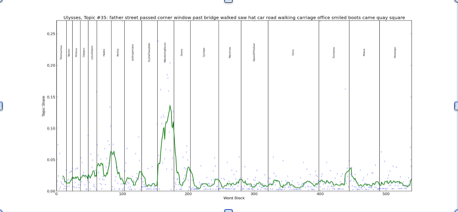

While such confirmation is useful, topic modeling also exposes patterns of language and meaning that have remained hidden to scholars. Consider Topic 35, which is highly associated with the words street, passed, corner, past, bridge, and walked. We might describe this topic as a “walking” topic, or more broadly, an “urban-spatial” topic. A graph showing the fluctuation of this topic across the novel tells us that it peaks in the “Wandering Rocks” episode (Figure 2). This again confirms what we know. This episode, as its most literal level, narrates the physical meanderings of several characters, such as Father Conmee, across the urban landscape of Dublin. The words associated with this movement are what the topic model has picked up on. Yet if we look at the topic’s overall distribution, what is surprising is its sustained presence across multiple earlier episodes, such as “Hades” and “Aeolus.” We know that both are framed by Leopold Bloom walking to or from a specific location, but the strength and persistence of the topic across and through these episodes is nevertheless striking.

Figure 2. A visualization of the relative topic share of “Topic 35” in each 500 word block of Ulysses. The points on the graph indicate the exact share for each block. The line represents a running average of these values.

Few scholars would say that a main organizing theme of “Hades” is its urban landscape. More typically, it is concepts, such as death and memory (particularly Bloom’s recollection of his father’s suicide), that are said to animate the form of the episode.[10] Discrete words like “street” or “car” are seen as mere scaffolding for this larger thematic action. What the topic model results suggest, however, is that this scaffolding may have a larger symbolic function as part of a cluster of words related to movement. Consider a passage from “Hades” that the model identifies as thickly materializing Topic 35: “Mr Powers choked laugh burst quietly in the carriage. Nelsons pillar … We had better look a little serious, Martin Cunningham said. Mr Dedalus sighed. Ah then indeed, he said, poor little Paddy wouldnt grudge us a laugh. Many a good one he told himself. The Lord forgive me! Mr Power said, wiping his wet eyes with his fingers. Poor Paddy!” What seem to be inconsequential markers of space or movement at the level of the individual passage (here captured in the word “carriage”), are exposed as the verbal supports of more significant themes, like death. The topic model suggests that there is a latent, but necessary spatial-conceptual link reinforced within the episode. But also, and this is its most intriguing contribution to a re-evaluation of the novel’s serial origins, across episodes.

In connecting word counts to the history of the novel’s serialization, Bulson also finds something interesting about the “Hades” episode. It is here that the episodes start getting longer. The reason, he speculates, is because the physical world of the narrative also began to “expand,” with interactions between characters becoming more complex. As a result, Joyce needed more words. It is with “Hades” that Joyce began rethinking the overall design of his work, imagining each future installment as potentially longer than the last, and thus transforming the kinds of things he could write about. What topic modeling adds to this argument is a way to see not just how serialization was changing Joyce’s attitude about how many words he could write, but in how many different combinations he could write them. Given the chance to pack in more and more information, we have to wonder how he decided to organize that information differently. Looking at Topic 35 again, it seems significant that Joyce was laying the groundwork in “Hades” for one part of a verbal system that would become greatly extended in “Wandering Rocks.” What might other topics reveal about the evolution of Joyce’s “blocks of words” as serialization of the work progressed?

These are the kinds of questions that will most likely appeal to literary critics and validate the felt usefulness of numbers as an interpretive method. More work, naturally, is needed to take these questions further. But Bulson’s essay, as well as our brief extension of his project, point to a new interpretative model for the modernist novel. Some will continue to insist that word counts or empirical models do violence to readings of Ulysses: such texts do not signify meaning via the quantity or collocations of words, but through the attention of individual human readers to the words on the page. We would not quarrel with that. Ulysses does not signify through word counts and topic models, but it can still be known through them. Indeed, the history of scholarship has left us a view of the novel as a mass of words that needs to be classified and schematized. As Kenner puts it, the novel is a “hail of information” that can be “retrieved and systematized,” and only through this labor do we “know a fraction of what we may think we know.” Bulson has shown how as simple a process as counting words can make new sense of this “hail.” With topic modeling, this project can be extended even further, inviting Ulysses into a much longer history of information theory. Not, however, because Joyce’s text can be construed as “information” in ways commensurable with current quantitative or computational methods. But precisely the opposite. Its incommensurability with the ontology of these methods exposes the continuities and ruptures that the novel shares with the contemporary information age and the tools that seek to order it. It is within this zone of continuity and discontinuity that new forms of reading will emerge.

[1] Hugh Kenner, Ulysses (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1980), 24.

[2] Kenner, 106.

[3] Here we refer to Kenner’s famous description of Ulysses as pulled together by some great “arranger.” Ibid., 61-71.

[4] David M. Blei, “Probabilistic Topic Models,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 55, no. 4 (April 2012), 77-78.

[5] For more thorough discussions of topic modeling as applied to literary and historical texts, see Matthew L. Jockers, Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2013), ch. 8; Andrew Goldstone and Ted Underwood, “The Quiet Transformations of Literary Studies: What Thirteen Thousand Scholars Could Tell Us,” New Literary History, vol. 45, no. 3 (Summer, 2014): 359-384; Tim R. Tangherlini and Peter Leonard, “Trawling in the Sea of the Great Unread: Sub-Corpus Topic Modeling and Humanities Research,” Poetics, vol. 41, no. 6 (December, 2013): 725:749; and also Lisa M. Rhody, “Topic Modeling and Figurative Language,” Journal of Digital Humanities, vol. 2, no. 1 (Winter, 2012).

[6] Blei, 79.

[7] Kenner, 23. See also Derek Attridge, “Introduction,” in James Joyce’s Ulysses: A Casebook (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 3-11.

[8] Before running the topic model, we excluded all grammatical function words as well as all personal names and all character names. For the personal names, we used Jockers’s expanded stopword list. See Macroanalysis, ch. 8.

[9] See Attridge, 10-11, for an excellent review of this scholarship and what it accomplished.

[10] See Michael Seidel, Epic Geography: James Joyce’s Ulysses (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 161, for just one recent example.