In the wake of New Historicism, eight music scholars reflect on the recent tendency to use objets trouvés and historical micronarratives for interpretation. The editors of the forum, Nicholas Mathew and Mary Ann Smart, introduce the thread of the quirk historicist phenomenon and contemplate its implications.

ELEPHANTS IN THE MUSIC ROOM: THE FUTURE OF QUIRK HISTORICISM

This introduction begins (free download):

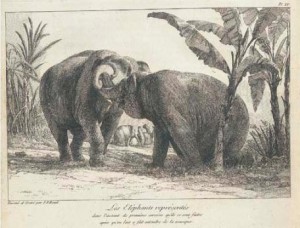

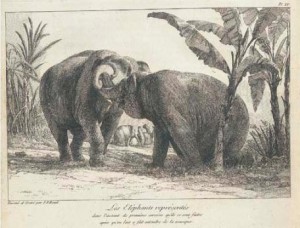

Jean Pierre Louis Laurent Houël: ‘‘Les eléphants représentes dans l’instant de premières caresses qu’ils se sont faites après qu’on leur a fait entendre de la musique,” in Histoire Naturelle des deux Elephants, male et femelle, du Muséum de Paris (Paris, 1803).

Despite a suffix that suggests kinship with taxonomic enterprises such as zoology or the earliest phases of anthropology, musicology may rank as one of the most permissive of humanistic fields. In journals and at conferences, philological research and source studies rub shoulders with work on the philosophy of music, close readings, reception history, and microhistory. Yet, as in literary studies, one central question has troubled the field for at least a quarter-century: that of the status of the “texts” (musical works, as notated or performed) whose interpretation and explanation traditionally anchored much musicological writing. As both the canon of works that merited this type of attention and the analytical tools used to explicate them were destabilized, scholarly energies turned toward narrating historical accounts of musical environments. In the wake of this suspicion of close reading, many musicologists became collectors of curiosities, assembling and scrutinizing disparate objects, events, and documents in order to understand how past communities of listeners and practitioners used music, why they created and cared about the kinds of music they did.

Before this collecting impulse took hold, history often meant “context.” Musical works could be enriched, but at the same time shown to be functional and contingent, by accounts that placed them in ready-made historical frames supplied by the locations in which art was produced or by big-picture histories—the French Revolution, the Third Reich, the Napoleonic Wars. And like most such cross-disciplinary borrowings, the imported concepts were sometimes flattened out, as if they had passed through the brain’s “abstract thought” region, as imagined in the Pixar movie Inside Out. As the kinds of history practiced by music historians have become more fine-grained and more material, there is a temptation to look down on earlier approaches as schematic or simplistic; but it is worth remembering that those contextual dyads (“music and . . . ”) were welcome and necessary excuses to talk about music—even instrumental music, symphonies and the like—in relation to categories such as gender, race, and nation, whose admission into musicological thought was long overdue.

Once musicologists began to take notice of New Historicism, any such tidy or schematic versions of history quickly fell by the wayside. New Historicism’s trademark deployment of the anecdote upended the apparent clarity and coherence of context and blurred the distinction between texts and contexts, dispersing both into more complex discursive constellations. The kinds of historical material potentially available to the music scholar thus became nearly endless, the relevance of any particular detail depending mainly on the ingenuity and persuasive gifts of the writer. Such a précis could, with a few adjustments, apply to almost any humanistic discipline in the 1990s and 2000s. But in musicology, the objets trouvés and historical micronarratives that once obediently fell into contextual patterns or acted as isolated anecdotes have staged a kind of mutiny, multiplying in the service of a narrative logic that overwhelms and even supplants any larger critical goals. It is this tendency that we are calling quirk historicism. Continue reading … (free download)

FORUM CONTENTS

JAMES Q. DAVIES

On Being Moved/Against Objectivity

EMILY I. DOLAN

Musicology in the Garden

ELLEN LOCKHART

Pygmalion and the Music of Mere Interest

AOIFE MONKS

Bad Art, Quirky Modernism

BENJAMIN PIEKUT

Pigeons

BENJAMIN WALTON

Quirk Shame

NICHOLAS MATHEW is Associate Professor of Music at the University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of Political Beethoven (Cambridge, 2013) and co-editor, with Benjamin Walton, of the collection The Invention of Beethoven and Rossini.

MARY ANN SMART also teaches in the Music Department of UC Berkeley. She is the author of Mimomania: Music and Gesture in Nineteenth-Century Opera and editor of Siren Songs: Representations of Gender and Sexuality in Opera. Her new book, Waiting for Verdi, will be published by the University of California Press in 2016.

Nicholas Mathew

Nicholas Mathew