No Problem

by Michael Fried

This essay, from the special issue “Description Across Disciplines,” is a reflection on the supposed difficulties of “description” in the writing of art history and art criticism. It begins:

Let me hoist up an epigraph, which I mean to wave brightly over everything I shall go on to say, from Ludwig Wittgenstein (no surprise, to anyone familiar with my writing): “The light shed by work is a beautiful light, but it only shines with real beauty if it is illuminated by yet another light.” Let me repeat it, the thought is so foreign to our usual assumptions: “The light shed by work is a beautiful light, but it only shines with real beauty if it is illuminated by yet another light.” I will proceed by making several somewhat general points, which I will try to back up with examples mainly from my own work.

The first point is this: I stand strongly opposed to the idea that there is some special problem—some problem of a theoretical or systematic nature—involved in describing works of (so-called) visual art. This means, to cite a famous text, that I find myself in disagreement with the views put forward in Michael Baxandall’s well-known essay “The Language of Art History” (1991), where he raises a number of problems of a general nature, the most important of which is the lack of fit, as he understands it, between the “linearity” of language and the non-“linearity” of pictures. In contrast to language, he writes, “a picture . . . or rather our perception of it, has no such inherent progression to withstand the sequence of language applied to it” (notice the metaphorics of this: “to withstand”—as if some kind of struggle is going on, with language as the aggressor; “the sequence of language applied to it”—as if slapped or thrust onto the picture’s surface; no suggestion here that a picture might welcome the right language, as if having waited for it nearly forever: think of my epigraph). Baxandall continues in the same vein: “An extended description of a painting is committed by the structure of language to be a progressive violation of the pattern of perceiving a painting. We do not see linearly. We perceive a picture by a temporal sequence of scanning, but within the first second or so of this scanning we have an impression of the whole—that it is a Mother and Child sitting in a hall, say, or a sort of geometricized guitar on a table” (459–60). We then observe greater and greater detail, including relationships among elements, but whatever our progress of seeing and noticing is like, “It is not comparable in regularity and control with progress through a piece of language” (460). Superior art writers (he mentions Giorgio Vasari and Charles Baudelaire) find ways to deal with this mismatch, Baxandall concedes. But in his view there remains a basic disparity between the circumstances of the literary critic on the one hand and an art historian or art critic on the other, for the simple reason that a literary text and our reception of it “have a robust syntagmatic progression of their own which the linear sequence of an exposition cannot harm” (460). Again, the imagery is that of a struggle, in which sequences of words seek to impose themselves damagingly on—more strongly, to violate—an artifact that by virtue of its inherent nature does its best to resist them. Indeed, Baxandall refers in these pages to “the basic absurdity of verbalizing about pictures” (461), as if the very project of seeking to do so were somehow under a cloud. (I find this a bit too British-commonsensical; why should verbalizing about pictures be thought of as more absurd than verbalizing about human relationships or, indeed, any other serious topic?) Continue reading …

MICHAEL FRIED is J. R. Herbert Boone Emeritus Professor of Humanities and the History of Art at the Johns Hopkins University. A new book of poems, Promesse du Bonheur, with photographs by James Welling, has just been published by David Zwirner Books.

is J. R. Herbert Boone Emeritus Professor of Humanities and the History of Art at the Johns Hopkins University. A new book of poems, Promesse du Bonheur, with photographs by James Welling, has just been published by David Zwirner Books.

What do we require of these pages? Or, to anthropomorphize and so shift the emphasis: what do they require of us? Such questions are at once theoretical and methodological, and the potential answers are so varied that reducing them to any binary between x or y way of proceeding would clearly be insufficient. Nonetheless, at present one pair of options stands out among others: should we interpret or should we describe? Is our task as readers, viewers, critics, scholars, and theorists the interpretive one of assigning or discerning meaning, crafting a reading, making the object of our attention speak its hidden truth? Or is it, on the contrary, the descriptive one of limning all the details, redoubling the object in our commentary on it, refusing the obviousness of the obvious by exhaustively accounting for what is to be read or seen?

What do we require of these pages? Or, to anthropomorphize and so shift the emphasis: what do they require of us? Such questions are at once theoretical and methodological, and the potential answers are so varied that reducing them to any binary between x or y way of proceeding would clearly be insufficient. Nonetheless, at present one pair of options stands out among others: should we interpret or should we describe? Is our task as readers, viewers, critics, scholars, and theorists the interpretive one of assigning or discerning meaning, crafting a reading, making the object of our attention speak its hidden truth? Or is it, on the contrary, the descriptive one of limning all the details, redoubling the object in our commentary on it, refusing the obviousness of the obvious by exhaustively accounting for what is to be read or seen? GEORGINA KLEEGE

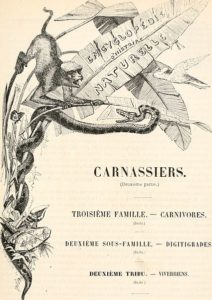

GEORGINA KLEEGE In what follows, I will look at two writers from the French eighteenth century whose work illustrates the contingency of modern categories and definitions of description. The first is the famous naturalist and renowned stylist Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, whose multivolume Histoire naturelle spurred the vogue for natural history across Europe in the second half of the eighteenth century. The second is the once-celebrated but now obscure poet Jacques Delille, who took the Scottish poet James Thomson as his model and introduced the so-called genre of descriptive poetry in France in the last decades of the Old Regime. Taken together, these two writers exemplify what the great naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier called “the age of description.” This age has fallen out of view since Cuvier’s lifetime, lost to the modern fracture between literature and science. Yet I will argue that it holds special relevance for us today, at a time when short-story writers and political theorists alike share an impulse to ascribe agency to nonhuman things and to question the centrality of human perspectives. One of the biggest surprises to emerge from the unfamiliar landscape of the eighteenth-century age of description is its elaboration of a poetics of description grounded in dramatic shifts in scale and nonhuman perspectives on nature.

In what follows, I will look at two writers from the French eighteenth century whose work illustrates the contingency of modern categories and definitions of description. The first is the famous naturalist and renowned stylist Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, whose multivolume Histoire naturelle spurred the vogue for natural history across Europe in the second half of the eighteenth century. The second is the once-celebrated but now obscure poet Jacques Delille, who took the Scottish poet James Thomson as his model and introduced the so-called genre of descriptive poetry in France in the last decades of the Old Regime. Taken together, these two writers exemplify what the great naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier called “the age of description.” This age has fallen out of view since Cuvier’s lifetime, lost to the modern fracture between literature and science. Yet I will argue that it holds special relevance for us today, at a time when short-story writers and political theorists alike share an impulse to ascribe agency to nonhuman things and to question the centrality of human perspectives. One of the biggest surprises to emerge from the unfamiliar landscape of the eighteenth-century age of description is its elaboration of a poetics of description grounded in dramatic shifts in scale and nonhuman perspectives on nature.