Who Are Vera and Tatiana? The Female Russian Nihilist in the Fin de Siècle Imagination

by Abby Holekamp

Focusing on a close, contextualized reading of a single case of invented identity from 1906, Abby Holekamp illustrates how, in fin de siècle Europe, a mutually generative relationship between the real, the imagined, and the rapidly proliferating mass media transformed the female “nihilist” from an apocryphal Russian figure into a durable Russian archetype—an archetype that had significant consequences in the shaping of European public opinion about Russia.

The essay begins:

In the French National Archives, there is a foot-high folder comprising fin de siècle surveillance reports concerning foreign revolutionary activity on French soil. It contains only one photograph, which shows a woman with dark, chin-length hair, positioned outdoors on an expanse of cobblestone, near a window covered by metal bars. She stands with one hand on the back of a wooden chair and the other on her hip. She wears a black, feathered straw hat and a bolero jacket with decorative trim—an outfit, in the words of the accompanying police report, that “left a little to be desired.” As with many old photographic portraits that required protracted stillness from their subjects, the woman’s expression is difficult to discern, though she does appear to be smiling slightly. On the thick card stock of the photograph’s reverse is a label: “Nihiliste russe arrêtée le 24 septembre à Toulouse” (Russian nihilist arrested September 24 in Toulouse).

In the French National Archives, there is a foot-high folder comprising fin de siècle surveillance reports concerning foreign revolutionary activity on French soil. It contains only one photograph, which shows a woman with dark, chin-length hair, positioned outdoors on an expanse of cobblestone, near a window covered by metal bars. She stands with one hand on the back of a wooden chair and the other on her hip. She wears a black, feathered straw hat and a bolero jacket with decorative trim—an outfit, in the words of the accompanying police report, that “left a little to be desired.” As with many old photographic portraits that required protracted stillness from their subjects, the woman’s expression is difficult to discern, though she does appear to be smiling slightly. On the thick card stock of the photograph’s reverse is a label: “Nihiliste russe arrêtée le 24 septembre à Toulouse” (Russian nihilist arrested September 24 in Toulouse).

Who was this young Russian nihilist arrested in September 1906 on suspicion of possessing a bomb meant for a Russian governor who happened at the time to be traveling in the south of France? This image of her was reproduced both as a photograph and as a drawing in French newspapers, as police worked to discern her identity. She was held in police custody over the next several days, during which time she repeatedly refused to tell police her name. As the authorities worked to identify her, the mysterious story of the unidentified jeune nihiliste russe spread rapidly through the national press. Between September 25 and October 3, 1906, a flurry of police and press reports conveyed and circulated the particulars of the ongoing investigation, and from the start, reports noted the inconsistencies in her story.

Two days after her arrest, the mysterious young woman told police she was born in Odessa and that her father, an engineer, had been killed in an uprising there, during which she herself had been injured by the sabre of a Russian officer, her hands lacerated by its blade. At the same time, the highest-circulation daily newspaper in Paris, Le Petit Parisien, which had picked up the story, reported that this “new Tatiana” was from Ekaterinoslav. In this account, her parents were reported to have moved to Ekaterinoslav from Saint Petersburg, where they had “a very comfortable lifestyle.” Somewhat unusual for a woman at the time, the young nihilist had received a classical education, studying Greek, Latin, and the sciences. As a result, she spoke several languages: not only her own “Slavic tongue” but also Czech, German, and a bit of French. She undertook university studies in Saint Petersburg and Lausanne. Her hands had been injured in Saint Petersburg during the failed 1905 revolution (referred to somewhat dismissively by the newspaper as an échauffourée—a scuffle or brawl). After healing—she had to keep her hands in a special apparatus for two months—she traveled once again to Lausanne, where, in the company of her fellow nihilists, the current ostensible plot began to take shape.

In short order, a new police report revealed more about the young woman’s movements in the region; more important, thanks to the recollection of a railway station buffet proprietor, a name finally emerged: Dolorès Valbritat Sanguinoff. The lexical connection of her purported surname to the word sanguin, with its bloody connotation, seemed oddly coincidental. It was reported that the buffet proprietor had listened to her story and, when subsequently questioned about it by the police, said he thought the whole bomb business was a sham. And indeed, there was no sign of a bomb. The jeune nihiliste, now known as Mademoiselle Sanguinoff, claimed to have thrown it into the Garonne River. In her presence, the authorities attempted to fish it out, but to no avail: the bomb was never found.

From here, the young woman’s story continued to unravel. On September 29, Mademoiselle Sanguinoff was positively identified by two medical students who had treated her in a Paris hospital, but who knew her as Dolorès Sanguinotti (or Sanguinetti). They believed she had recently worked for an oil merchant in Marseille, and they recalled that she had struck them as intelligent and well educated, and that she spoke correct French, albeit with a strong southern accent. On October 1, Le Petit Parisien asked the question: Was this woman indeed the same person who was treated for an abscess in October at the Lariboisière Hospital in Paris? When later confronted in court by the two medical students, the young woman was reported to have blushed and wept, asking, “Why are you doing this?” To which the judge replied, “Because we have to know who you are and why you’ve been leading us on for a week.” The jeune nihiliste consented to explain, but insisted that no journalists be present during her conversation with the judge. She said she was afraid of newspapers and what they would say about her.

By October 3, the young woman’s true identity was established. She was, in reality, one Jeanne Tilly, born in Brest on September 27, 1887. She had previously been convicted of fraud. There was no bomb in her possession, nor had there ever been. Some of what she subsequently reported about her early life in Brittany and in Paris was corroborated by other people, but large parts of her story remained dubious, especially her supposed dealings with nihilists. By persisting in this rather intricate charade, Jeanne Tilly not only frustrated police and court authorities; she was also accused of making fools out of them, the press, and the broader public. She achieved a couple of weeks of notoriety as her story and image appeared in multiple mass-circulation publications. Eventually, she was tried on charges of vagrancy. On December 12, 1906, she was acquitted. The information on her acquittal comes from an account in the 1908 doctoral thesis of a deputy judge from a small town near Toulouse. Titled “Contempt Against Judges,” the thesis deals with the concept of contempt of court and briefly details the facts of the Jeanne Tilly case in a footnote to a section on “imaginary crimes.”

What happened to Tilly following her acquittal remains unclear. In the absence of evidence, we cannot definitively answer the question of why a provincial French youth invented this plausible backstory for her “imaginary crime,” but in asking how she was able to do so, we find ample evidence that female Russian nihilists were an object of particular fascination not only in the imagination of fin de siècle France but also throughout Western Europe.[iv] In asking how images of the female Russian nihilist lingered in the European imagination a generation after her moment had passed in Russia, we can analyze a foundational example of what Michael C. Frank has called “the cultural imaginary of terrorism.” Frank argues that from the late nineteenth century through to the post-9/11 world, fact and fiction have been inextricably entangled in public discourse about terrorism. This cultural imaginary is not wholly created by fictional representations of terrorism in novels and movies, but is instead generated when “these fictions exploit a propensity for fantasy already present in both terrorist activities and the discourse surrounding them.”[v] One of the first theorists of the “cultural imaginary,” Cornelius Castoriadis, distinguished between imagination and imaginary (in Castoriadis’s French original: imagination and imaginaire) by distinguishing between the individual person and the social collective: both have an imagination, but the imaginary belongs solely to the collective. This is the distinction I mean to evoke by using the term “cultural imaginary,” because this essay explores the interaction between an individual imagination—Tilly’s—and the collective discourses that were available to her. In the formulation of Graham Dawson, cultural imaginaries provide “public forms which both organize knowledge of the social world and give shape to phantasies within the apparently ‘internal’ domain of psychic life.” The importance of the Tilly episode derives from the raw—albeit fleeting—credibility of her invented biography, not only an artifact of a particular moment in European history but also one that sheds light on more contemporary issues regarding the public’s relationship with terrorism.

In exploring the manifestations of this cultural imaginary through the lens of Tilly’s exploit, I draw on Iurii Lotman’s work on the semiotics of behavior in imperial Russia. Lotman described the conscious “theatricality” of the behavior of early-nineteenth-century Russian nobles and attributed it to their interactions with romantic and sentimental texts. Other scholars have picked up Lotman’s analysis of the aspiring Decembrist revolutionaries in particular and applied his approach to Russian radicals (and later, terrorists) of the 1860s to 1880s who were inspired by reading the realist works of Nikolai Chernyshevsky and his contemporaries. I suggest that this approach can be usefully applied to a subsequent transnational popularization of radical archetypes such as the female Russian nihilist, which was made possible by the rapid development of mass media in fin de siècle Europe. The very term “nihilist” was essentially a fictional construct in this later historical context. The original nihilists of the mid-nineteenth century were first analyzed through and then transformed by fictional texts. By 1906, the way in which Tilly’s actions made an increasingly imaginary construct real exemplified how mass media shaped and sustained a feedback loop between the real and the imaginary. This mutually generative relationship illustrates the importance of analyzing the effects of cultural imaginaries on everyday life.

To be sure, there were female terrorists (especially in the Russian context) and an increase in terrorism was of genuine concern in fin de siècle Europe. But the signifiers of “female Russian nihilist” were imaginary in the way Frank and Dawson use the term; per Lotman, Tilly’s behavior—theatrical in its own way—was inspired by the media she consumed. So, on the one hand, the nihilist was not real; she was, rather, a representation, an image, a confection that was propagated and promoted in particular ways, within a rapidly changing information ecosystem. On the other hand, she was very real as an archetype through which fin de siècle Europeans formulated knowledge about Russia and the “East.” If the nihilist was imaginary, it did not matter, and this was in part because there was a blurred boundary between fact and fiction built into the contemporary media landscape.

This essay explores the real consequences of an imaginary construct. Before Tilly was identified, a Swiss newspaper asked if she was actually given instructions and tools to carry out a bombing, or if instead “she had an idée fixe caused by reading about terrorist attacks.” As part of a broader cultural imaginary, Tilly’s alleged idée fixe was shared by a much more extensive reading public. These kinds of fantastic images were not necessarily created by mass media, but they were certainly bolstered by it, and they were as important as more formal transnational, diplomatic, or political relations as factors in shaping public opinion about Russia in this period because they were accessible to a much wider swath of society, including provincial French youths like Tilly. Continue reading …

ABBY HOLEKAMP is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at Georgetown University. Her research focuses on the transnational interplay of French and Russian revolutionary cultures from the 1880s through the 1930s.

In recognition of the impact of Covid-19 on campus instruction and the rise of unplanned distance learning, UC Press is pleased to make Representations and all of its online journals content free to all through June 2020.

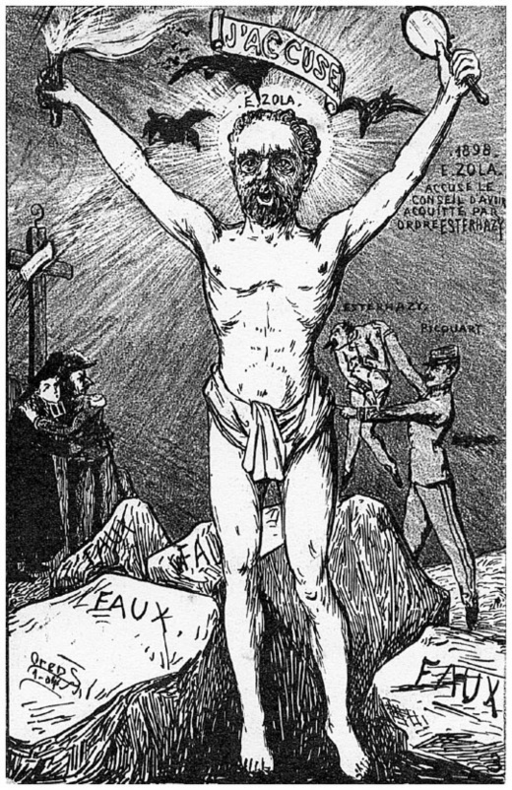

Oscar Wilde and Émile Zola are conventionally opposed as the figureheads of, respectively, the aestheticist and the naturalist literary trends. Yet they exhibit a number of uncanny similarities—not least the turn both made in their last years toward religious themes and imagery, and especially those of martyrdom and the Passion. In this essay Andrew Counter explores such images in the later life, work, and public persona of each writer and sets them within the context of the dizzying proliferation of references to Christ and martyrdom in fin de siècle culture. He examines the “entailments”—the unexpected consequences, meanings, and echoes—that these overdetermined themes brought in their train from the wider literary field and shows how those entailments were exacerbated by the massive politicization of “martyr” discourse around the time of the Dreyfus affair, when the theme acquired its fullest significance.

Oscar Wilde and Émile Zola are conventionally opposed as the figureheads of, respectively, the aestheticist and the naturalist literary trends. Yet they exhibit a number of uncanny similarities—not least the turn both made in their last years toward religious themes and imagery, and especially those of martyrdom and the Passion. In this essay Andrew Counter explores such images in the later life, work, and public persona of each writer and sets them within the context of the dizzying proliferation of references to Christ and martyrdom in fin de siècle culture. He examines the “entailments”—the unexpected consequences, meanings, and echoes—that these overdetermined themes brought in their train from the wider literary field and shows how those entailments were exacerbated by the massive politicization of “martyr” discourse around the time of the Dreyfus affair, when the theme acquired its fullest significance. ANDREW J. COUNTER

ANDREW J. COUNTER