Tutankhamun in West Germany, 1980–81

by Mario Schulze

The essay opens:

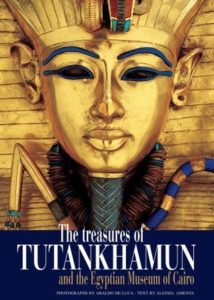

When I began my research on the Tutankhamun exhibitions, I repeatedly came across one remarkable motif in the archives: quite a few of the remaining photos of the exhibition show the golden funeral mask of the famous ancient Egyptian pharaoh, the most important piece of the exhibition, facing at eye level a high-ranking representative of the country in which the exhibition was then appearing. These pictures call to mind a diplomatic meeting of two states or a state visit across time. Instead of the mandatory handshake between the two leaders, the photos give the impression of eye contact between the Egyptian mask and the queen of England or the presidents of the United States or the Federal Republic of Germany. The photos portray the Western leaders not as connoisseurs in the act of examining a work of art but as reverential admirers of a foreign leader. When the leaders are joined by experts, as in the photograph of President Jimmy Carter with the director of the National Gallery in Washington, John Carter Brown, the experts appear redundant. It looks as if Carter is not even listening to Brown but communing instead with Tutankhamun.  In Germany, this connection between the leader and the artifact was so evident that the popular tabloid Bild even expressed concerns about why the German president stood so far away from the mask during his visit. The explanation, that the president was farsighted, made it clear, nonetheless, that this was an intimate meeting between two leaders. All of these pictures suggest that Tutankhamun’s golden mask was more than just a beautiful, awe-inspiring artifact; it was an ambassador.

In Germany, this connection between the leader and the artifact was so evident that the popular tabloid Bild even expressed concerns about why the German president stood so far away from the mask during his visit. The explanation, that the president was farsighted, made it clear, nonetheless, that this was an intimate meeting between two leaders. All of these pictures suggest that Tutankhamun’s golden mask was more than just a beautiful, awe-inspiring artifact; it was an ambassador.

There have been several exhibitions of objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun since its famous discovery by the British archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922. The best known, and the one of interest here, is the Treasures of Tutankhamun tour of 1972 – 1981. At first fifty and then fifty-five tomb artifacts were exhibited in the United Kingdom (London); in the Soviet Union (Moscow, Leningrad, and Kiev); in seven cities in the United States; in Toronto, Canada; and, finally, in five cities in the Federal Republic of Germany, where it was renamed Tutanchamun. The 1970s world tour is considered the most popular exhibition of all time, having broken records for attendance at almost every participating museum—records that for the most part still stand today. Especially in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Germany the “King Tut” show became a pop-cultural phenomenon: “Tutmania.” The exhibition received massive news coverage from tabloids and broadsheets alike. Even on TV, King Tut was everywhere. Although large-scale art exhibitions with hundreds of thousands of visitors had taken place as early as the mid-nineteenth century, the Tut exhibition was the prime example of a new exhibition genre. It became “the ultimate blockbuster,” as the director of the New York Metropolitan Museum, Thomas Hoving, wrote in his memoir. The exhibition was highly successful not only in terms of visitors and media coverage but also because it produced huge revenues for Egypt, which lent the touring objects, and for museums and tourist industries around the world. As such, the 1970s Tut exhibition is interesting on many levels: in its expression of a new exhibition boom, in its exemplification of the postmodern commodification of culture, and in the negotiation of the gender relations and racial identities that intersected in the course of the exhibition.

In this essay I am concerned with the diplomatic dimensions of the blockbuster. News reports on the Tut exhibition often pointed out that the objects, and particularly the gold mask, were not simply museum artifacts but objects of ambassadorial status. The small German newspaper of Southern Schleswig explicitly headlined: “Tut—Egypt’s Special Ambassador.” Other newspapers celebrated the mask as the “King of Egypt” and representative of Egyptian state power. They reported on the way the mask was treated as a state guest, transported by the Luftwaffe (German airforce), and continually guarded by Egyptian and German security forces.

The political charge of the objects was obviously an integral part of the massive appeal of the show in the Western world. But it is not for political reasons alone that the ambassadorial status of museum objects deserves a closer look in the context of the contemporary history of exhibitions. How did Tutankhamun’s grave goods become ambassadors? Or, to put it more broadly: what is the state-political dimension of traveling museum objects and, in particular, of very mobile and world-famous star objects? Continue reading …

Schulze’s essay tells the diplomatic history of the Treasures of Tutankhamun touring exhibition, the most successful exhibition of all time, and its engagement in West Germany. It argues that the exhibition ascribed an ambassadorial role to its objects and used them as a tool of diplomatic propaganda. While the visit of the objects was promoted as an attempt at cross-cultural understanding, the interpretation and commodification of the exhibits also served to justify the West’s appropriation of Egypt’s natural and cultural resources.

MARIO SCHULZE is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Zurich University of Arts. As member of the research group “Mobile Objects,” a project of Humboldt University’s Interdisciplinary Laboratory for Image, Knowledge, and Gestaltung at the Museum of Natural History in Berlin, he is writing a book on the Tutankhamun exhibitions.

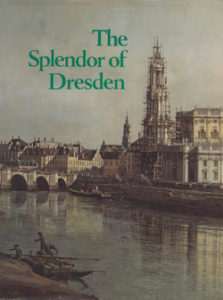

On June 1, 1978, The Splendor of Dresden: 500 Years of Art Collecting opened in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. At the entrance to the massive exhibition, two life-size mannequins on horseback, outfitted in ornate armor, lunged at each other in mid-joust: a preview for visitors of the spectacular onslaught of cultural objects across twenty-two galleries in the brand new East Building beyond (fig. 1). The impact of Splendor was both political and aesthetic. This was the first major loan of art from the German Democratic Republic (GDR) to the United States, initiated immediately after the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries just four years earlier. Billed as a grand gesture of cultural exchange in the spirit of the Helsinki Accords, the exhibition was the product of unprecedented collaboration between American and East German museum officials in an environment of intense mutual suspicion at the highest political levels. The gradual erosion of détente in the late 1970s set the stage for a telling opening scene: the dinner planned to celebrate the exhibition’s installation in the National Gallery was deferred to accommodate the NATO summit taking place concurrently in Washington. At the same time that NATO delegates were committing to increase defense spending in response to Soviet military advantage in central Europe, their wives, hosted at a preview tea by First Lady Rosalynn Carter, were among the exhibition’s first visitors.

On June 1, 1978, The Splendor of Dresden: 500 Years of Art Collecting opened in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. At the entrance to the massive exhibition, two life-size mannequins on horseback, outfitted in ornate armor, lunged at each other in mid-joust: a preview for visitors of the spectacular onslaught of cultural objects across twenty-two galleries in the brand new East Building beyond (fig. 1). The impact of Splendor was both political and aesthetic. This was the first major loan of art from the German Democratic Republic (GDR) to the United States, initiated immediately after the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries just four years earlier. Billed as a grand gesture of cultural exchange in the spirit of the Helsinki Accords, the exhibition was the product of unprecedented collaboration between American and East German museum officials in an environment of intense mutual suspicion at the highest political levels. The gradual erosion of détente in the late 1970s set the stage for a telling opening scene: the dinner planned to celebrate the exhibition’s installation in the National Gallery was deferred to accommodate the NATO summit taking place concurrently in Washington. At the same time that NATO delegates were committing to increase defense spending in response to Soviet military advantage in central Europe, their wives, hosted at a preview tea by First Lady Rosalynn Carter, were among the exhibition’s first visitors.