Wilde, Zola, Dreyfus, Christ: Fin de Siècle Passions

by Andrew J. Counter

Oscar Wilde and Émile Zola are conventionally opposed as the figureheads of, respectively, the aestheticist and the naturalist literary trends. Yet they exhibit a number of uncanny similarities—not least the turn both made in their last years toward religious themes and imagery, and especially those of martyrdom and the Passion. In this essay Andrew Counter explores such images in the later life, work, and public persona of each writer and sets them within the context of the dizzying proliferation of references to Christ and martyrdom in fin de siècle culture. He examines the “entailments”—the unexpected consequences, meanings, and echoes—that these overdetermined themes brought in their train from the wider literary field and shows how those entailments were exacerbated by the massive politicization of “martyr” discourse around the time of the Dreyfus affair, when the theme acquired its fullest significance.

Oscar Wilde and Émile Zola are conventionally opposed as the figureheads of, respectively, the aestheticist and the naturalist literary trends. Yet they exhibit a number of uncanny similarities—not least the turn both made in their last years toward religious themes and imagery, and especially those of martyrdom and the Passion. In this essay Andrew Counter explores such images in the later life, work, and public persona of each writer and sets them within the context of the dizzying proliferation of references to Christ and martyrdom in fin de siècle culture. He examines the “entailments”—the unexpected consequences, meanings, and echoes—that these overdetermined themes brought in their train from the wider literary field and shows how those entailments were exacerbated by the massive politicization of “martyr” discourse around the time of the Dreyfus affair, when the theme acquired its fullest significance.

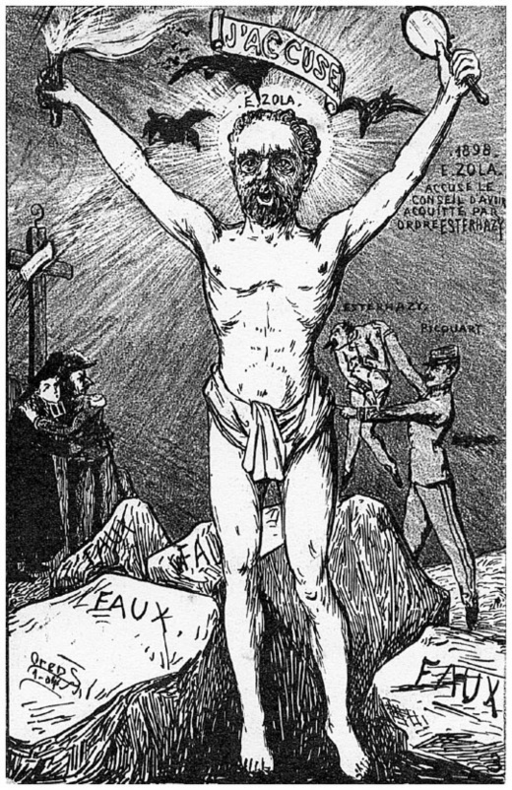

Image: Orens Denizard (“Orens”), “Zola accuse le Conseil . . . ,” 1899, collected in postcard series Le Calvaire Dreyfus, 1904. Bibliothèque historique de la Ville de Paris.

The essay begins:

On 5 January 1895, the courtyard of the École Militaire in Paris witnessed a scene of ritualized public humiliation. Captain Alfred Dreyfus, convicted of treason against the French Republic by a military tribunal the previous month, was brought into the courtyard for his ceremonial degradation, in which the epaulettes, insignia, and sleeves were torn from his uniform and his sword broken, all before a crowd of soldiers and, beyond them, a civilian mob shouting insults. A week later, on 13 January, Henri Meyer’s famous drawing of the scene appeared on the cover of Le Petit Journal, expanding that crowd to include the rest of France, and the world. The following month, Dreyfus would begin his journey to Devil’s Island and his sentence of penal servitude for life.

Later that year, on 20 November, in another country, another public humiliation occurred. Oscar Wilde, already serving a sentence of two years’ imprisonment with hard labor for acts of gross indecency, was transferred by train from Pentonville Prison in London to Reading Prison, a journey that necessitated a change at Clapham Junction station. As Wilde would later recall in the prison manuscript subsequently published as De profundis:

On November 13th, 1895, I was brought down here from London. From two o’clock till half-past two on that day I had to stand on the centre platform of Clapham Junction in convict dress, and handcuffed, for the world to look at. . . . Of all possible objects I was the most grotesque. When people saw me they laughed. Each train as it came up swelled the audience. Nothing could exceed their amusement. That was, of course, before they knew who I was. As soon as they had been informed they laughed still more. For half an hour I stood there in the grey November rain surrounded by a jeering mob.

Wilde’s sometime friend Robert Sherard noted in 1916, some years after Wilde’s death, that when Wilde first recounted this “outrage” to him during a visit to Reading Prison, he had suggested that it was “even worse than what Wilde relates” in De profundis: “I was told that the man who first recognized the prisoner shouted: ‘By God, that is Oscar Wilde,’ and spat on him.”

Back to Paris, and forward to early 1898. In what Pierre Birnbaum has dubbed “the anti-Semitic moment,” the city and France at large were in the grip of frenzied anti-Semitic hatred and frequent mob violence. At the beginning of February, not quite a month after the publication of the open letter known as “J’accuse. . . !,” Émile Zola stood trial for libel against the army general staff and a military tribunal held the previous month, whom he had accused of knowingly obstructing justice by exonerating Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy (now widely suspected of being the true traitor) and reaffirming the 1894 conviction of Dreyfus. Leaving the Palais de Justice after the first few days of hearings, Zola was greeted by baying crowds shrieking “Down with Zola! Down with the Jews!” and threatening violence that was narrowly averted by police action. The scene is dramatically immortalized in Henry de Groux’s painting of the same year, Zola aux outrages, in which a multitude of distorted, hate-filled faces surges menacingly toward the lonely novelist, whose frock coat appears symbolically white in the painting’s muddy palette. Zola would subsequently be found guilty and his conviction upheld on appeal, forcing him into miserable exile in England in July 1898.

These episodes have some obvious commonalities. In all three cases, an individual is shamed and abused for a crime of which he is factually or, in Wilde’s case, morally innocent. All three occur at a frightening threshold between the formal yet flawed procedures of state justice, and an undisciplined wellspring of negative communal affect that threatens to explode—one meaning of the “passions” of my title. And all three were spoken of at the time as “martyrdoms,” or discussed through analogies with the Passion of Jesus Christ. As a number of scholars have shown, the Passion was one of the primary metaphorical languages of the discourse of the Dreyfus affair, on both the Dreyfusard and anti-Dreyfusard sides. While Dreyfus’s likening to a martyr or to Christ was among the more problematic instances of this language (though not, as we shall see, the most problematic), that association was certainly made—not least by Zola himself. In an open letter to Mme Dreyfus after Dreyfus’s acceptance of a presidential pardon in September 1899, Zola referred to her husband as “the crucified” and of his plight as a “martyrdom,” and rejoiced that he had now been “brought down from his cross.” Wilde’s susceptibility to the theme, meanwhile, is well known—“Even before the misery of his own trial in 1895 . . . , Wilde’s early writings reveal a preoccupation with martyrdom,” writes Jan-Melissa Schramm—and the passage of De profundis describing the incident at Clapham Junction is explicitly prefaced in this direction: “It is said that all martyrdoms seemed mean to the looker on. The nineteenth century is no exception to the rule” (DP, 187). And if Zola made a rhetorical martyr of Dreyfus, he himself received what Christopher Forth calls “the full Jesus treatment” in the works of others: in its composition and title, for instance, de Groux’s painting of the scenes outside the Palais de Justice deliberately evoked his 1889 work Le Christ aux outrages, which had depicted Jesus taunted by a bloodthirsty crowd.

Despite, moreover, the copious gestures of support and encouragement that Zola received during this period (of which the painting is an example), this sort of rhetoric tended for strategic purposes toward self-erasure, in that it presented its protagonist as the entirely friendless victim of unanimous condemnation and contempt. Indeed, Zola himself could not resist the temptation to reimagine his 1898 experiences in these terms when he drew on them for a scene in his novel Travail (1901), the second in his planned series of Quatre Évangiles—“four gospels.” In book 2, the protagonist, Luc Froment, a visionary socialist industrialist and Zola’s proxy in the novel, having just been exonerated of causing the disappearance of a local stream through the improvement works he has undertaken at his factory for the future benefit of all, is hounded through town by a superstitious mob:

Ah! That climb up the rue de Brias, with the swelling crowd of enemies at his heels, beneath the ignominious stream of outrages and threats! . . . What had he done these last four years, for so much hate to have built up against him, to be hunted down like this by the crowd, howling like a pack of wolves for his death? What gall, what suffering there is in the shared Calvary every righteous man must ascend, as the blows of those he has tried to redeem rain down upon him! . . . Now they were stoning him. He made no gesture, but continued to climb his Calvary. (OC, 19:159–60)

Though Luc, as is required by the titular logic of Zola’s “gospels,” takes his name from the Evangelist, his experience in these pages is obviously modeled on Christ’s own: Luc’s humiliation is a Calvary, and this via dolorosa tacitly endorses representations of Zola’s own experience of public opprobrium as Christlike.

These three episodes are positioned at a fin de siècle confluence in which references to Christ, the Passion, and the figure of the martyr more broadly proliferated. In the 1890s, images drawn from these instantly recognizable narratives were appropriated for aesthetic, political, and personal purposes that might be of the most contradictory sorts. As a favored topos of the Decadent imagination as well as of a nascent homosexual aesthetic sensibility; as an apparently inevitable structuring metaphor for the sectarian confrontations of the Dreyfus affair; and as an inviting rhetoric for the utopian political ideologies of the fin de siècle, Christ and martyr imagery offered at once a seemingly very reliable mode of generating meaning, but also, I shall suggest, an oddly risky one, given the overdetermination of such imagery occasioned by its very promiscuousness in these competing fin de siècle discourses. In this article, I explore such acts of appropriation and their attendant rhetorical risks in the later life, work, and public image of Oscar Wilde and Émile Zola, including as each of these intersected with the Dreyfus affair, with a view to understanding, first, their purpose in adopting Christological or martyrological references and imagery; and second, the consequences—unintended and conceivably unconscious—of their doing so for the tone, style, and coherence of their work. These unintended consequences or risks are what I shall refer to as the “entailments” of the Christ reference.

This essay is thus a contribution to a potentially very revealing literary comparison between Wilde and Zola. I choose these two writers as figures who stood, as Wilde put it of himself, “in symbolic relations to the art and culture of [their] age” (DP, 162), and first and foremost as handy metonymies, then and now, for what a traditional literary history has tended to regard as the two competing literary postulations of the fin de siècle: the Naturalist versus the Decadent, the hypermimetic versus the hyperartificial. Yet both writers are also somehow quintessentially “fin de siècle,” to the extent that Max Nordau in Degeneration (1892) denounces both as equally symptomatic of the social and cultural pathologies he associates with that phrase. In his recollections of Wilde, indeed, Vincent O’Sullivan recalls the playwright noting that “great antipathy shews secret affinity”; when O’Sullivan waggishly inquired whether this meant that Wilde had an affinity to George Moore, the Irish naturalist who was a particular bête noire of Wilde’s, he allegedly replied: “No; but perhaps to Zola. Still, I hope not.” I find this exchange plausible largely because it is so well observed: for all their differences, as I shall show, these are indeed two writers who exhibit some uncanny similarities—not least in the shape of their own internal contradictions, contradictions that emerge most visibly in the “religious,” which is not to say orthodox, turn of their later years.

My hunch is that this “secret affinity” between Wilde and Zola has much to teach us about the fin de siècle literary field in Europe. In this article, however, I limit myself to considering what these two figures and their (self-)positioning vis-à-vis fin de siècle cultural discourses of martyrology and the Passion can reveal about the complex and shifting interactions of a number of phenomena. Wilde’s and Zola’s late religious preoccupations, I shall suggest, afford a privileged glimpse into the entanglements of politics, sexuality, mass culture, and literary form at a moment of particular social crisis in France. I explore these in four discrete but connected sections, each of which addresses a different aspect of the Christ or martyr theme. Continue reading …

ANDREW J. COUNTER is Associate Professor of French at the University of Oxford and the author of Inheritance in Nineteenth-Century French Culture: Wealth, Knowledge and the Family (Legenda, 2010) and The Amorous Restoration: Love, Sex and Politics in Early Nineteenth-Century France (Oxford University Press, 2016). His current book project is provisionally entitled Thinking Sexual Ethics with Modern French Literature.

ANDREW J. COUNTER is Associate Professor of French at the University of Oxford and the author of Inheritance in Nineteenth-Century French Culture: Wealth, Knowledge and the Family (Legenda, 2010) and The Amorous Restoration: Love, Sex and Politics in Early Nineteenth-Century France (Oxford University Press, 2016). His current book project is provisionally entitled Thinking Sexual Ethics with Modern French Literature.