Fugitive Voice

by Martha Feldman

Read free of charge for a limited time

In this essay Martha Feldman proposes that current-day notions of fugitivity, understood in the terms Fred Moten delineates as a category of the irregular that escapes easy representations and predications, can undiscipline music histories in productive ways. Among these: it can inflect musicological thinking through attention to sonic remainders of haunted pasts; it can decenter understandings of the aesthetic; and it can lead to more nuanced thinking about the imbrication of music in an “undercommons” of life that refuses ever to fully sound in harmony, residing instead in a disordered space of restless, noisy sound. Feldman asks, finally, how such thinking, developed by Moten, Nathaniel Mackey, and Daphne Brooks, among others, can remake aspects of musicological thinking about voice.

In this essay Martha Feldman proposes that current-day notions of fugitivity, understood in the terms Fred Moten delineates as a category of the irregular that escapes easy representations and predications, can undiscipline music histories in productive ways. Among these: it can inflect musicological thinking through attention to sonic remainders of haunted pasts; it can decenter understandings of the aesthetic; and it can lead to more nuanced thinking about the imbrication of music in an “undercommons” of life that refuses ever to fully sound in harmony, residing instead in a disordered space of restless, noisy sound. Feldman asks, finally, how such thinking, developed by Moten, Nathaniel Mackey, and Daphne Brooks, among others, can remake aspects of musicological thinking about voice.

The essay begins:

A vibrant strain of avant-garde writing is nowadays centering music as the medium of a luminously varied Black radical aesthetic without much of musicology yet noticing. Such work might bring to mind sonic points along a dolorous history, from “the deep meaning of those rude and apparently incoherent songs” of slaves traveling to receive their monthly food allowance that Frederick Douglass heard on the plantation—what W. E. B. Du Bois called “sorrow songs,” “through which the slave spoke to the world”—to the stirring blues laments of Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, and Nina Simone brought to light by modern-day Black feminists. Today’s Back avant-garde stretches out from such moments, addressing long histories of racial subjugation and violence intimately bound up with modern histories of capitalism, but it’s up to something different. It understands its aesthetic objects through a nexus of politics, philosophy, and metaphysics that often goes by the name of fugitivity, a concept that encompasses those earlier soundings while resituating them. Not restricted to literal flight from slavery, fugitivity belongs to what philosopher and poet Fred Moten—thus far its most expansive and challenging theorist—describes as a capacious category of the irregular in which freedom and unfreedom perpetually coexist in persons who refuse to be objectified or reduced. Only when a Black being recognizes their oppression, victimization, or commodification by speaking, talking back, or refusing to be named and delimited does fugitivity become a lived reality. Only then does it move in its characteristic temporal arc, bending toward the future even while haunted by a past that is never past. Moten conveys this existential condition in a disarming passage about the resonance between the slave narrative passed down to posterity by Harriet Jacobs (1861) and a nude photograph of an anonymous prepubescent Black girl captured in 1882 in the studio of Philadelphia artist Thomas Eakins:

The moment in which you enter into the knowledge of slavery, of yourself as a slave, is the moment you begin to think about freedom, the moment in which you know or begin to know or to produce knowledge of freedom, the moment at which you become a fugitive, the moment at which you begin to escape in ways that trouble the structures of subjection that—as Hartman shows with such severe clarity—overdetermine freedom. This is the musical moment of the photograph.

Provocatively, fugitivity here, regardless of its expressive medium, has a consistency that is decidedly musical.

I want to pause at this juncture—obscure at its surface, for how can a photograph without an iota of literal sound have a “musical moment”?—because the notion is pivotal, turning on what Moten elsewhere calls “visible sound.” Avid readers of Moten will recall another photograph that clamors at various points in his prose, that of the desecrated body of young Emmett Till, whose mother insisted he be displayed in all the horror of his savage murder. The image contains what Moten calls an “extensional cry and sound,” one whose power to overtake the viewer’s senses ignites the memory with a disturbance that transduces other senses, other embodied memories.

An image from which one turns is immediately caught in the production of its memorialized, re-membered reproduction. You lean into it but you can’t; the aesthetic and philosophical arrangements of the photograph . . . anticipate a looking that cannot be sustained as unalloyed looking but must be accompanied by listening and this, even though what is listened to—echo of a whistle or a phrase, moaning, mourning, desperate testimony and flight—is also unbearable. These are the complex musics of the photograph. This is the sound before the photograph.

The music sounds before the camera clicks, before the viewer views, and sounds again once the viewer looks. Music both precedes and expresses Black life. It triggers memories that turn into griefs and horrors, more images, and (as we learn elsewhere) bundles of sensory events beyond the strictly auditory or visual. Not just unidirectional, however, medial/sensory transformations and intermediations also go the other way. Hence Jacobs, at a devastating moment in her account, hears “a band of serenaders . . . under the window, playing ‘Home Sweet Home,’” which soon turns into the sounding image of moaning children.

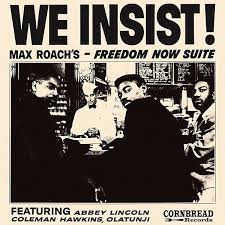

Music here is no more resident solely in physical sound than in sounding music. Wherever found, Black music registers fugitive escape via the phonic eruption, which equates to Black experience and is prefigured by the scream or cry whose originary American instance (to which Moten turns twice, following Saidiya Hartman) are the screams of Frederick Douglass’s Aunt Hester being viciously beaten by her owner. Contained “in the break” (the main title of Moten’s first book), the cry disrupts conventional grammars, strictures, and forms, indexing a breakdown or breakage, but also, relatedly, a breakthrough—a Black event that moves the subject from bondage, conscription, and silence to flight, marronage, and voice. Such flight takes the form of a literal (and for Moten paradigmatic) scream in Abbey Lincoln’s performance of Max Roach and Oscar Brown Jr.’s Freedom Now Suite (1960), a piece that is otherwise “musical” in the ordinary sense. But fugitive flight also takes other sonic forms: a plangent, wailing jazz solo; the explosive shouts in James Brown’s “Cold Sweat”; the lyrical, dancing rhythms of Rakim’s hip-hop, for example—all instances of Moten’s philosophies repeatedly articulating the Black radical aesthetic that Michael Gallope describes “as folds, blurs, oscillations, and rewinds; as displacement and dispossession; as the entanglement of lyricism, performativity, improvisation, and virtuosity.” Continue reading …

Music here is no more resident solely in physical sound than in sounding music. Wherever found, Black music registers fugitive escape via the phonic eruption, which equates to Black experience and is prefigured by the scream or cry whose originary American instance (to which Moten turns twice, following Saidiya Hartman) are the screams of Frederick Douglass’s Aunt Hester being viciously beaten by her owner. Contained “in the break” (the main title of Moten’s first book), the cry disrupts conventional grammars, strictures, and forms, indexing a breakdown or breakage, but also, relatedly, a breakthrough—a Black event that moves the subject from bondage, conscription, and silence to flight, marronage, and voice. Such flight takes the form of a literal (and for Moten paradigmatic) scream in Abbey Lincoln’s performance of Max Roach and Oscar Brown Jr.’s Freedom Now Suite (1960), a piece that is otherwise “musical” in the ordinary sense. But fugitive flight also takes other sonic forms: a plangent, wailing jazz solo; the explosive shouts in James Brown’s “Cold Sweat”; the lyrical, dancing rhythms of Rakim’s hip-hop, for example—all instances of Moten’s philosophies repeatedly articulating the Black radical aesthetic that Michael Gallope describes “as folds, blurs, oscillations, and rewinds; as displacement and dispossession; as the entanglement of lyricism, performativity, improvisation, and virtuosity.” Continue reading …

MARTHA FELDMAN is the Edwin A. and Betty L. Bergman Distinguished Service Professor of Music at the University of Chicago. Her books include Opera and Sovereignty (Chicago, 2007), The Castrato (Oakland, 2015), and the coedited The Voice as Something More: Essays toward Materiality (Chicago, 2019). She is now working on a book on castrato phantoms in twentieth-century Rome.

MARTHA FELDMAN is the Edwin A. and Betty L. Bergman Distinguished Service Professor of Music at the University of Chicago. Her books include Opera and Sovereignty (Chicago, 2007), The Castrato (Oakland, 2015), and the coedited The Voice as Something More: Essays toward Materiality (Chicago, 2019). She is now working on a book on castrato phantoms in twentieth-century Rome.

“Lately, across the humanities, historicism in its many guises has been in retreat—a retreat that music studies has in some respects hastened. This collection of essays asks why sound and music appear to induce exhaustion with history and historical method and how a renewed focus on musical practices might motivate fresh histories and novel forms of history writing.” –from the editors’ introduction

“Lately, across the humanities, historicism in its many guises has been in retreat—a retreat that music studies has in some respects hastened. This collection of essays asks why sound and music appear to induce exhaustion with history and historical method and how a renewed focus on musical practices might motivate fresh histories and novel forms of history writing.” –from the editors’ introduction

Roger Mathew Grant

Roger Mathew Grant I had been spending some time in the country there, and on quiet nights with moderate winds I used distinctly to hear long, held tones, which would begin to resemble a deep, subdued organ pipe, then also the vibrations from the ringing of a muffled bell. I often could discern precisely the deep F and the striking C a fifth above it, and often even the E-flat a minor third above that also sounded, so that this piercing seventh chord, in the tones of the deepest lamentations, filled my chest with an innermost penetrating melancholy, and even horror.

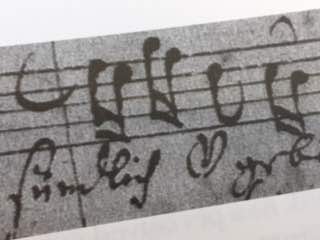

I had been spending some time in the country there, and on quiet nights with moderate winds I used distinctly to hear long, held tones, which would begin to resemble a deep, subdued organ pipe, then also the vibrations from the ringing of a muffled bell. I often could discern precisely the deep F and the striking C a fifth above it, and often even the E-flat a minor third above that also sounded, so that this piercing seventh chord, in the tones of the deepest lamentations, filled my chest with an innermost penetrating melancholy, and even horror. There is a notational oddity in the autograph score of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cantata 199, “Mein Herze schwimmt im Blut” (My heart is swimming in blood). Instead of writing out the word “heart” every time it appears in the text, at several points the composer used the familiar heart symbol—not exactly shaped like the physical organ, but apparently as instantly recognizable then as it is now. In some instances, the abbreviation may have resulted from pragmatic considerations of space, but in others clearly not. Instead, perhaps Bach was invoking, in an inconsequential and semi-private manner, the rich significatory potential of this pictogram. Already by the early seventeenth century, the heart image had come to appear frequently in a variety of contexts, from courtly chivalry and religious iconography to sets of playing cards, encompassing an extensive field of associations and meanings. Severed from the human body, the organ could be subjected to a dazzling variety of treatments, as in the extraordinary Emblemata sacra (1622) by the German Lutheran theologian Daniel Cramer. In this widely distributed volume of devotional emblems, the heart appears in no fewer than fifty different scenarios, demonstrating its protean capacity to stand in for the believer’s life, soul, conscience, consciousness, memory, earthly existence, or inner self: the heart as a rock being softened by God’s hammer, a winged heart escaping from the claws of earthly demons up to heaven, the heart with a seeing eye, Jesus inscribing his name on the heart, the heart adrift in a stormy sea, a burning heart filled with cooling liquid from the Holy Spirit, the heart’s mettle being tested in a hot oven, and so on.

There is a notational oddity in the autograph score of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cantata 199, “Mein Herze schwimmt im Blut” (My heart is swimming in blood). Instead of writing out the word “heart” every time it appears in the text, at several points the composer used the familiar heart symbol—not exactly shaped like the physical organ, but apparently as instantly recognizable then as it is now. In some instances, the abbreviation may have resulted from pragmatic considerations of space, but in others clearly not. Instead, perhaps Bach was invoking, in an inconsequential and semi-private manner, the rich significatory potential of this pictogram. Already by the early seventeenth century, the heart image had come to appear frequently in a variety of contexts, from courtly chivalry and religious iconography to sets of playing cards, encompassing an extensive field of associations and meanings. Severed from the human body, the organ could be subjected to a dazzling variety of treatments, as in the extraordinary Emblemata sacra (1622) by the German Lutheran theologian Daniel Cramer. In this widely distributed volume of devotional emblems, the heart appears in no fewer than fifty different scenarios, demonstrating its protean capacity to stand in for the believer’s life, soul, conscience, consciousness, memory, earthly existence, or inner self: the heart as a rock being softened by God’s hammer, a winged heart escaping from the claws of earthly demons up to heaven, the heart with a seeing eye, Jesus inscribing his name on the heart, the heart adrift in a stormy sea, a burning heart filled with cooling liquid from the Holy Spirit, the heart’s mettle being tested in a hot oven, and so on.