by Randall Meissen

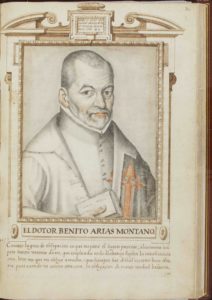

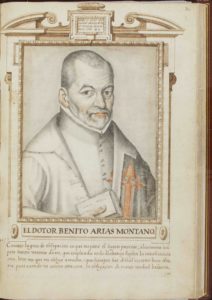

Francisco Pacheco, portrait of Benito Arias Montano, c. 1580–1644. IB 15654, Biblioteca Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid.

Francisco Pacheco, portrait of Benito Arias Montano, c. 1580–1644. IB 15654, Biblioteca Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid.

The essay begins:

Pacheco was the foremost art theorist of his generation, a longtime member of Seville’s famed humanistic academy, and both father-in-law and mentor to two of the most prominent artists of the Spanish baroque, Alonzo Cano (1601–67) and Diego Velázquez (1599–1660). Pacheco’s unfinished manuscript book, Libro de descripción de verdaderos retratos, de illustres y memorables varones (Book of description of true portraits of illustrious and memorable men), currently held at the Lázaro Galdiano Museum in Madrid, was a work in progress for most of his professional life, as he gradually compiled it from 1599 until his death in 1644. The manuscript consists of fifty-six portrait drawings by Pacheco and forty-four short biographical texts on authors, artists, ecclesiastics, and other men of accomplishment. Most of the biographies are straightforward, consisting of a description of the individual’s education, notable military or literary achievements, any written or artistic works, connection to Seville (however slight), and occasional brief anecdotes highlighting the individual’s moral character.

In his treatise Arte de la pintura (On the art of painting; Seville, 1649), Pacheco indicated that he had drawn more than 170 portraits in black and red pencil with the intention of selecting from them up to one hundred eminent individuals representing all fields of learning. The physical construction of the Libro de retratos, evident from several of the unfinished sections, demonstrates Pacheco’s process, as he described it, of drawing, retaining, and selecting the portraits over many years. Seven loose, single-sheet portrait-biographies that he chose not to incorporate into his manuscript book still survive at the library of the Palacio real in Madrid. Pacheco cut each portrait from its original sheet, pasted it onto a sheet of the manuscript, and then framed it with architectural ornamentation drawn in ink and washed in sepia tones. At the top of each finished frame, Pacheco added a biblical verse, and along the lower edge he placed the individual’s name in capitals.

A completed portrait and biography in Pacheco’s Libro consisted of a single sheet folded in half to form two folios. A succinct two- to three-page biographical description followed each finished portrait and often concluded with an epithet or poem. Most of the biographies recorded the death of the individual, and some portraits of individuals who survived Pacheco have blank pages where the biography would go, a detail that suggests Pacheco avoided writing a person’s definitive biography until the ink upon the pages of their life had dried.

Pacheco chose to adopt a genre of historical writing with a classical genealogy for the preservation of Seville’s recent historical memory. The De viris illustribus (“on illustrious men”) genre, which can be traced back to Plutarch and Cicero, experienced a renewed popularity during the Renaissance. Pacheco was familiar with the illustrated editions of famous men by the Italian humanist Paolo Giovio (1483–1552) and the subsequent work on the lives of artists by Giorgio Vasari (1511–74). Pacheco lamented that although in other nations, “particularly Italy,” art itself was honored by those who wrote the lives of illustrious artists, “only our nation lacks that praiseworthy endeavor,” and artists themselves were to blame. Apparently Pacheco took it upon himself to remedy this shortfall, and he was uniquely well suited for such an undertaking. Unlike Giovio or Vasari, who depended on artists and engravers to translate their projects into print, Pacheco had complete control over both the text and the images of his manuscript book.

The Libro de retratos is in fact a visual history. In its recovery and preservation of a visual record of an illustrious past, it confirms that such a practice existed in Pacheco’s era. It was a practice manifested in a transmedial application of methods adapted from humanistic textual scholarship and early modern antiquarianism as they were applied to artistic media for the preservation and communication of historical knowledge. To understand his Libro it must be recognized that Pacheco constructed his images by basing them on other credible visual sources (employing a method I call visual philology). One might mistake the portraits for illustrations of the text, but instead the texts “illustrate” or describe the portraits, as Pacheco made explicit by titling the collection of works Book of Description of True Portraits.

His Libro is thus a useful object for exploring questions of material culture relevant to visual studies scholars, historians of the book, and early modernists. Pacheco’s claim to produce true portraits was closely related to the distinctive ways antiquarians and ecclesiastics of his era used material evidence to stake truth claims about the ancient world and about the virtuousness of historical personages, respectively. Pacheco attempted to show certain qualities of historical personages—such as prestige, prosperity, illustriousness, and holiness—that were tightly bound to display, pageantry, costume, and liturgy in Seville. My essay, then, will demonstrate how three intertwined visual cultures produced by the antiquarian reimagining of Seville’s Roman past, Catholic Counter-Reformation image theory, and the publishing conventions of Sevillian humanism shaped Pacheco’s expectations about how an illustrious past should look. Let’s consider first how Seville’s elites used reimagined classical imagery to celebrate the glory of their city and how Pacheco employed that visual vocabulary in his Libro. Continue reading …

Francisco Pacheco (1564–1644), the foremost Spanish art theorist of his generation, worked on his manuscript Libro de verdaderos retratos (Book of true portraits) for more than forty years. In this essay Randall Meissen addresses how the visual cultures of Pacheco’s Seville, especially the city’s reimagined imperial Roman past, Catholic Counter-Reformation image praxis, and visual conventions of Renaissance humanism, shaped Pacheco’s conception of how an illustrious past could be recovered and shown.

RANDALL MEISSEN is a PhD candidate in history at the University of Southern California and predoctoral fellow at the USC-Huntington Early Modern Studies Institute. He has held short-term fellowships at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California; the John Carter Brown Library in Providence, Rhode Island; and the Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Saint Louis University in St. Louis, Missouri.

What happened when the most important genre of Renaissance painting, the historia (a “visual history”), built its images on scenes of eyewitnessed current events disseminated in the new medium of print? Is it a coincidence that a new claim to the eyewitnessing of current events in paint occurred in the fifteenth century, around the time that print made such palpably new histories available to a wide audience? While this essay will not undertake to prove that mechanical reproducibility put pressure on the historia to disseminate events as they appeared and as they happened, it will attempt to show the transformative encounter of these two things. A series of representations of a signal historical event enables us to see the convergence of the eyewitnessed image and print in action, and I propose to treat the meeting of the Council of Trent (1545–63) as my example, in part out of perversity. This event, which was in reality a visually uninteresting series of meetings (rows of people talking) spanning decades, was represented in a way that was both more textured and detailed than previous such scenes. And the long arc of time over which the council met was dealt with visually by representing what appears to be a single moment, a radical (and arbitrary) condensation in pictures—in a manner equivalent to the boiling down of a long war, with its many skirmishes, by representing a single moment in a single battle that in itself may have been of no particular significance. We will see, though, that a visual history that looks right to the eye in a given instant is still an image that has been put to work by specific agents. It was usually not sufficient merely to show a historical event; the artist had to make sense of it, to interpret it, to declare a position. The historia remained intact, and yet the eyewitnessed image, by virtue of its visual media, also had a stimulating effect as evidence-based history. Continue reading …

What happened when the most important genre of Renaissance painting, the historia (a “visual history”), built its images on scenes of eyewitnessed current events disseminated in the new medium of print? Is it a coincidence that a new claim to the eyewitnessing of current events in paint occurred in the fifteenth century, around the time that print made such palpably new histories available to a wide audience? While this essay will not undertake to prove that mechanical reproducibility put pressure on the historia to disseminate events as they appeared and as they happened, it will attempt to show the transformative encounter of these two things. A series of representations of a signal historical event enables us to see the convergence of the eyewitnessed image and print in action, and I propose to treat the meeting of the Council of Trent (1545–63) as my example, in part out of perversity. This event, which was in reality a visually uninteresting series of meetings (rows of people talking) spanning decades, was represented in a way that was both more textured and detailed than previous such scenes. And the long arc of time over which the council met was dealt with visually by representing what appears to be a single moment, a radical (and arbitrary) condensation in pictures—in a manner equivalent to the boiling down of a long war, with its many skirmishes, by representing a single moment in a single battle that in itself may have been of no particular significance. We will see, though, that a visual history that looks right to the eye in a given instant is still an image that has been put to work by specific agents. It was usually not sufficient merely to show a historical event; the artist had to make sense of it, to interpret it, to declare a position. The historia remained intact, and yet the eyewitnessed image, by virtue of its visual media, also had a stimulating effect as evidence-based history. Continue reading … EVONNE LEVY is Professor of Early Modern Art History at the University of Toronto. She works on the art, architecture, and historiography of the baroque in Europe and Latin America.

EVONNE LEVY is Professor of Early Modern Art History at the University of Toronto. She works on the art, architecture, and historiography of the baroque in Europe and Latin America.

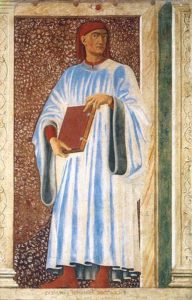

Boccaccio is generally the least appreciated of the “Three Crowns” of the Italian literary canon (after Petrarch and Dante), yet his focus on the realistic, even gritty details of everyday life, everyday characters, and everyday language has no real precedent, at least not one of the scope of the Decameron. Studies of the novel typically identify Boccaccio’s masterpiece as an influential precursor in the development of modern literary realism, and Erich Auerbach devotes a critical chapter to the Decameron in his monumental history of Western mimesis. Although recent scholarship has called into question Boccaccio’s supposed modernity, underlining the allegorical aspects of the Decameron and its continued debt to medieval textual practices, it is difficult to deny that, at the very least, Boccaccio expands the frame of what can be legitimately represented in literature.

Boccaccio is generally the least appreciated of the “Three Crowns” of the Italian literary canon (after Petrarch and Dante), yet his focus on the realistic, even gritty details of everyday life, everyday characters, and everyday language has no real precedent, at least not one of the scope of the Decameron. Studies of the novel typically identify Boccaccio’s masterpiece as an influential precursor in the development of modern literary realism, and Erich Auerbach devotes a critical chapter to the Decameron in his monumental history of Western mimesis. Although recent scholarship has called into question Boccaccio’s supposed modernity, underlining the allegorical aspects of the Decameron and its continued debt to medieval textual practices, it is difficult to deny that, at the very least, Boccaccio expands the frame of what can be legitimately represented in literature. Shakespeare’s plays were immensely popular in their own day yet history refuses to think of them as mass entertainment. In Pleasing Everyone, Professor of English Jeffrey Knapp highlights the uncanny resemblance between Renaissance drama and the incontrovertibly mass medium of Golden-Age Hollywood cinema. Through explorations of such famous plays as Hamlet, The Roaring Girl, and The Alchemist, and such celebrated films as Citizen Kane, The Jazz Singer, and City Lights, Knapp challenges some of our most basic assumptions about the relationship between art and mass audiences and encourages us to resist the prejudice that mass entertainment necessarily simplifies and cheapens.

Shakespeare’s plays were immensely popular in their own day yet history refuses to think of them as mass entertainment. In Pleasing Everyone, Professor of English Jeffrey Knapp highlights the uncanny resemblance between Renaissance drama and the incontrovertibly mass medium of Golden-Age Hollywood cinema. Through explorations of such famous plays as Hamlet, The Roaring Girl, and The Alchemist, and such celebrated films as Citizen Kane, The Jazz Singer, and City Lights, Knapp challenges some of our most basic assumptions about the relationship between art and mass audiences and encourages us to resist the prejudice that mass entertainment necessarily simplifies and cheapens.