by Aaron Rich

The essay begins:

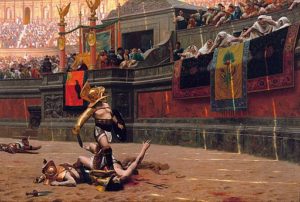

Pollice Verso by Jean-Léon Gérôme

Despite decades of being considered quite conventional, the French academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme has recently enjoyed a renewal of interest. The 2010 exhibition The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, in its catalog and in an accompanying collection of essays, argued that Gérôme was in fact a pioneer of modern painting. The exhibition and its publications make the case that Gérôme’s work is in fact protocinematic—in its engagement with subjects of large-scale spectacle, its circulation in secondary formats such as prints and photographs, and its use of strategies of duration and anticipation. While several authors discussed a few of his Roman paintings, such as Hail, Caesar! We Who Are About to Die Salute You (1859), The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer (1862–83), and Pollice Verso (1872), missing from their discussions was the fact that Hollywood studios actually used copies of these paintings in their background research for productions of films set in ancient Rome. An examination of the materials used as visual guidance for the 1951 production by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) of the Roman melodrama Quo Vadis, directed by Mervyn LeRoy, makes it clear that Gérôme’s paintings of the Circus Maximus, along with many other images of the ancient city by academic artists including Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Thomas Couture, and hundreds of popular illustrations and photographs of ancient sites, were used by Hollywood studios to understand and recreate the look and material culture of antiquity in a way the audience would recognize and enjoy.

Still from Quo Vadis

By the mid-1920s, nearly every Hollywood studio had already established a research library where extensive collections of visual materials, including illustrated books, magazines, and newspapers, as well as photographs, postcards, cartes de visite, stereo-view slides, maps, building blueprints, technical manuals, prints of paintings, and drawings were housed and managed. Their staff compiled these images into what they called “research bibles,” scrapbooks of thematically organized images. To obtain images that might help suggest a design for a prop or set, researchers scoured their own libraries; those of other studios; outside picture collections in the public libraries of Los Angeles, New York, London, and Paris; the Huntington Library; the libraries of the major universities of Los Angeles; the picture and photo collections of many state historical libraries; and the collections of other film services, such as Western Costume Company, the film industry’s largest costume maker. Research bibles helped film workers in managerial and craft departments—including producers, directors, writers, art directors, costume designers, hair and makeup designers, set decorators, and prop builders—visualize all sorts of mundane details, whether they were bowls, tables, and lamps or more exotic items like chariots, military uniforms, and fountains, to create believable cinematic environments. These multivolume collections could be reproduced, allowing every department to use the same visual sources simultaneously. The art department would see images of costumes, and the props department would see images of hair and makeup; all of a film’s creative crew had access to the same visual field. As a typical example, the Quo Vadis research bible contained five volumes, each focusing on a different element of the production: locations, costumes, sets, props, and sculpture from the ancient world.

Hollywood studio films made through the 1960s were part of a much larger “republic of images.” The depictions of the world, its people, and its material culture found in films circulated within a larger system of modern visual media that included illustrated books, the pictorial press, and other image-based materials. Much like the Republic of Letters of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, within which ideas and essays circulated among a class of learned people throughout Europe and North America, this twentieth-century visual network allowed for the wide dissemination of knowledge about the ancient and modern world throughout a broad, decentralized area. When producing movies, filmmakers were inspired by images gathered from a diverse set of illustrated sources that were recognizable to viewers precisely because such pictures were already circulating throughout many popular forms of media.

Scholarship regarding the research undertaken for Hollywood films has for the most part focused on issues of historical accuracy. In so doing, historians have often assumed that the films in question were simply renarrating written historical discourse, emphasizing the attention filmmakers showed to how these narratives were previously presented in literature, rather than considering how Hollywood cinema has recirculated a body of visual knowledge of the world of the past. Such scholarship has largely overlooked the fact that film research was largely picture-centered, using methods related to earlier visual practices from the centuries before the advent of cinema, and that Hollywood research departments were less concerned with accuracy than with gathering a large quantity of visual media about a time and place. It did not matter, for example, that statuary in antiquity was frequently polychromatic, richly decorated in bright colors; by the twentieth century, the film audience familiar with printed and projected depictions of ancient Rome would have assumed that the white marble sculpture most often depicted was historically accurate.

Stephen Bann has explained how inauthentic historical narratives and objects were popular with scholars and audiences alike from 1750 through the late nineteenth century. “The critical preoccupation with authenticity and the transgressive wish to simulate authenticity are, in a certain sense, two sides of the same coin,” he explained. But in Hollywood, all materials relating to a film’s subject, time period, characters, and material culture were considered when creating a film; authenticity was merely a marketing flourish. Standard practice in the industry involved visual research that considered a tremendous range of illustrated media from popular and scholarly sources, which together contributed to what Bann has called “historical poetics.” Such a practice combined historical details with entertainment and spectacle, often with a tinge of irony, to interest, amuse, and educate the audience. This heterogeneous mix of source materials also structured history museums, dioramas, panoramas, historical literature, and historical painting in the nineteenth century, and it is the most common way modern people have experienced history for the past three centuries. In this way, the question of whether or not a film presents an authentic historical narrative misses the point; Hollywood filmmakers were much more interested in presenting familiar images that the audience would recognize from many earlier and well-circulated depictions of the past, regardless of their historical validity.

In the case of Quo Vadis, the film narrative contains true historical events, such as Nero’s setting fire to Rome in 64 CE or the spectacle of the crucifixions of early Christians. But the film also refers to thousands of images and elements from visual depictions of the city created, for the most part, not from the first century but from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Anne Friedberg, referring to the late twentieth-century point of view, explains that history is “inexorably bound with images of a constructed past: a confusing blur of ‘simulated’ and ‘real.’” Through eighteenth- and nineteenth-century depictions of ancient Rome that were widely circulated in prints and illustrated journals, the modern understanding of the city changed to fit those images, and in turn, twentieth-century films were designed to echo those earlier images, using them as inspiration for their recreations of the ancient capital.

Likewise, nineteenth-century academic painters looked to earlier depictions of the past, including earlier narrative paintings and antiquarian images, to find visual inspiration for invented details. Gérôme, for example, gathered a tremendous volume of visual materials and pioneered the use of photographs to help him to recreate the material culture of the distant lands that were frequently his subject. He claimed that his Roman painting Pollice Verso was a depiction of gladiators in the Circus Maximus superior to his earlier Hail, Caesar! We Who Are About to Die Salute You because he had done more research on the armor and appearance of gladiators for the later picture. He explained that the accumulation of so many details helped to create an “accent of truth” that the audience would understand. Continue reading …

In this essay Aaron Rich shows describes the process by which Hollywood studio film productions through the 1960s used research to develop depictions of the past that would show audiences representations they would recognize and believe. He situates this research as part of a much larger and more complex republic of images through which pictures of the world, its people, and its material culture circulated within a system of modern media, including illustrated books, the pictorial press, and other image-based materials of which movies were a part. Rich then makes the case that Hollywood cinema should be reconsidered an essential part of the twentieth-century perception of history, regardless of the accuracy of its depictions.

AARON RICH is a PhD candidate in the division of Cinema and Media Studies in the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts. His dissertation, “The Hollywood Research Library: Visual Knowledge in the Republic of Images,” focuses on studio research departments that gathered images from popular media to guide craft departments in recreating the world and investigates how these picture collections emerge from a Western tradition of understanding and appreciating the past and present visually.

No one could have grasped the relationship between the discovery of civilizations of the remote past, the visualization of their antiquity, and modernity better than Charles Leonard Woolley. One of the most eminent archaeologists of the first half of the twentieth century, Woolley was a doyen of Near-Eastern ancient history, a manipulator of newly developed media, and a celebrity, who noted that “an appeal to the eye is the best way of awakening interest in a new form of knowledge” (that is, archaeology). His observation about the accessibility to mass audiences of a past that had hitherto been largely known only through texts, that had barely existed as a materiality, and that had to be literally dug up to be envisioned, is to be found in his popular manual, Digging Up the Past, which was based on a series of six talks broadcast on the BBC and first published in 1930. By that time Woolley had already written Ur of the Chaldees, which aimed at a popular reading public; had begun publishing the multivolume Excavations at Ur, for professionals; had regularly contributed to the British and North American press; and had toured Britain. As numerous British and American reviewers of the booklet remarked, it proved that archaeology “concerned everyone. Its subject is modern man.”

No one could have grasped the relationship between the discovery of civilizations of the remote past, the visualization of their antiquity, and modernity better than Charles Leonard Woolley. One of the most eminent archaeologists of the first half of the twentieth century, Woolley was a doyen of Near-Eastern ancient history, a manipulator of newly developed media, and a celebrity, who noted that “an appeal to the eye is the best way of awakening interest in a new form of knowledge” (that is, archaeology). His observation about the accessibility to mass audiences of a past that had hitherto been largely known only through texts, that had barely existed as a materiality, and that had to be literally dug up to be envisioned, is to be found in his popular manual, Digging Up the Past, which was based on a series of six talks broadcast on the BBC and first published in 1930. By that time Woolley had already written Ur of the Chaldees, which aimed at a popular reading public; had begun publishing the multivolume Excavations at Ur, for professionals; had regularly contributed to the British and North American press; and had toured Britain. As numerous British and American reviewers of the booklet remarked, it proved that archaeology “concerned everyone. Its subject is modern man.”

What happened when the most important genre of Renaissance painting, the historia (a “visual history”), built its images on scenes of eyewitnessed current events disseminated in the new medium of print? Is it a coincidence that a new claim to the eyewitnessing of current events in paint occurred in the fifteenth century, around the time that print made such palpably new histories available to a wide audience? While this essay will not undertake to prove that mechanical reproducibility put pressure on the historia to disseminate events as they appeared and as they happened, it will attempt to show the transformative encounter of these two things. A series of representations of a signal historical event enables us to see the convergence of the eyewitnessed image and print in action, and I propose to treat the meeting of the Council of Trent (1545–63) as my example, in part out of perversity. This event, which was in reality a visually uninteresting series of meetings (rows of people talking) spanning decades, was represented in a way that was both more textured and detailed than previous such scenes. And the long arc of time over which the council met was dealt with visually by representing what appears to be a single moment, a radical (and arbitrary) condensation in pictures—in a manner equivalent to the boiling down of a long war, with its many skirmishes, by representing a single moment in a single battle that in itself may have been of no particular significance. We will see, though, that a visual history that looks right to the eye in a given instant is still an image that has been put to work by specific agents. It was usually not sufficient merely to show a historical event; the artist had to make sense of it, to interpret it, to declare a position. The historia remained intact, and yet the eyewitnessed image, by virtue of its visual media, also had a stimulating effect as evidence-based history.

What happened when the most important genre of Renaissance painting, the historia (a “visual history”), built its images on scenes of eyewitnessed current events disseminated in the new medium of print? Is it a coincidence that a new claim to the eyewitnessing of current events in paint occurred in the fifteenth century, around the time that print made such palpably new histories available to a wide audience? While this essay will not undertake to prove that mechanical reproducibility put pressure on the historia to disseminate events as they appeared and as they happened, it will attempt to show the transformative encounter of these two things. A series of representations of a signal historical event enables us to see the convergence of the eyewitnessed image and print in action, and I propose to treat the meeting of the Council of Trent (1545–63) as my example, in part out of perversity. This event, which was in reality a visually uninteresting series of meetings (rows of people talking) spanning decades, was represented in a way that was both more textured and detailed than previous such scenes. And the long arc of time over which the council met was dealt with visually by representing what appears to be a single moment, a radical (and arbitrary) condensation in pictures—in a manner equivalent to the boiling down of a long war, with its many skirmishes, by representing a single moment in a single battle that in itself may have been of no particular significance. We will see, though, that a visual history that looks right to the eye in a given instant is still an image that has been put to work by specific agents. It was usually not sufficient merely to show a historical event; the artist had to make sense of it, to interpret it, to declare a position. The historia remained intact, and yet the eyewitnessed image, by virtue of its visual media, also had a stimulating effect as evidence-based history.  EVONNE LEVY

EVONNE LEVY Representations 145

Representations 145