by Sebastian LeCourt

The essay begins:

One curious feature of nineteenth-century British and American novels about Jesus is the fact that their central figure often remains largely offstage. In Harriet Martineau’s Traditions of Palestine (1830), William Ware’s Julian; or, Scenes in Judea (1841), Edwin A. Abbott’s Philochristus: Memoirs of a Disciple of the Lord (1878), Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880), James Freeman Clarke’s The Legend of Thomas Didymus: The Jewish Skeptic (1881), Marie Corelli’s Barabbas (1893), and Florence Morse Kingsley’s Titus, a Comrade of the Cross (1894), Jesus is pushed into the background while the narrative follows the life of a minor historical figure or the cultural milieu of first-century Palestine. Ware builds an elaborate character system out of various bit players from the canonical Gospels, turning Barabbas, the robber who is pardoned unwittingly in Jesus’s place, into Mary Magdalene’s ne’er-do-well brother and a proxy for her own narrative arc. Kingsley, beating Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) to the punch, forges a comic subplot out of the story of a cripple whom Jesus robs of employment: “Ha, fellow! thou didst heal me, three years ago, of the palsy, which had withered my limbs; and in so doing took away my living, for my begging no longer brought me money.” And behind all of this are elaborate historical backdrops drawn from both secular historiography and Holy Land tourist guidebooks.

One curious feature of nineteenth-century British and American novels about Jesus is the fact that their central figure often remains largely offstage. In Harriet Martineau’s Traditions of Palestine (1830), William Ware’s Julian; or, Scenes in Judea (1841), Edwin A. Abbott’s Philochristus: Memoirs of a Disciple of the Lord (1878), Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880), James Freeman Clarke’s The Legend of Thomas Didymus: The Jewish Skeptic (1881), Marie Corelli’s Barabbas (1893), and Florence Morse Kingsley’s Titus, a Comrade of the Cross (1894), Jesus is pushed into the background while the narrative follows the life of a minor historical figure or the cultural milieu of first-century Palestine. Ware builds an elaborate character system out of various bit players from the canonical Gospels, turning Barabbas, the robber who is pardoned unwittingly in Jesus’s place, into Mary Magdalene’s ne’er-do-well brother and a proxy for her own narrative arc. Kingsley, beating Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) to the punch, forges a comic subplot out of the story of a cripple whom Jesus robs of employment: “Ha, fellow! thou didst heal me, three years ago, of the palsy, which had withered my limbs; and in so doing took away my living, for my begging no longer brought me money.” And behind all of this are elaborate historical backdrops drawn from both secular historiography and Holy Land tourist guidebooks.

In many ways, of course, this pattern is exactly the one we might expect, since it exemplifies the core move of the classical historical novel described a century ago by Georg Lukács. According to Lukács, Walter Scott and his many imitators sought to shift readers’ attentions away from the lives of great heroes and toward the grassroots historical forces that helped produce them in the first place. As a result, those forgotten individuals who would have represented mere scenery to traditional historiography became protagonists themselves and the new privileged lens for understanding historical change. Although quite traditional within novel studies, this narrative has seen its currency revived lately by Alex Woloch’s The One vs. the Many (2003) as well as more recent essays by Julian Murphet, Emily Steinlight, Jesse Rosenthal, and others. One reason for its endurance is the fact that it forms part of a familiar account of secularization as the transfer of cultural privilege from the singular to the multiple and the special to the ordinary. What links secularization, democratization, and individualism, according to this narrative, is a desire to seek out meaning among undistinguished individuals and everyday life instead of established gods and kings.

Yet the reality is that many Victorian Jesus novels were authored not by writers of a secularist bent but rather by more orthodox figures. Even though they consigned Jesus to the margins of a realistic historical landscape, their avowed goal was nevertheless to affirm his status as an unparalleled personality in cosmic history. In this essay I argue that understanding why they did so offers us a chance to complicate our traditional association of historical realism with secularization and thereby illuminate a wider set of possibilities. Specifically, I want to replace the contrast between singularity and multiplicity with a less stable triangle of terms: the particularity of the random individual, the genericness of the recurring historical type, and the specialness of the Carlylean hero or prophet. These three ways of focalizing character—particularity, typicality, and specialness—blend into and oppose one another in ways that our binary modernization stories often fail to capture. Abstract typicality and novelistic particularity can both be used to argue against heroic specialness by portraying a figure like Jesus as an unremarkable iteration of a recurring type. But they can also be profoundly at odds with each other, a fact that allows novelistic realism to become the ally of theology.

In order to trace these dynamics in action, I situate the Victorian Jesus novel alongside the broader nineteenth-century enterprise called comparative religion. One central postulate of this emerging field was that religious founders such as Jesus and the Buddha were simultaneously historical and typical. Not only did they have idiosyncratic origin stories that could be documented in great detail, but they also represented instances of a type that recurred from age to age and culture to culture. Both assertions were designed to counter the notion of Christian exceptionality and to value a wider range of cultural materials under the label of religion. At the same time, comparative religion’s invocation of recurring types was profoundly at odds with its commitment to validating the particular and the various. For, in fact, Victorian scholars often found postbiblical religious founders such as Mohammed difficult to imagine as legitimate instances of the type precisely because there was such an abundance of information about them. They were hard pressed to square this new generic abstraction, “religion,” with the lives of actual historical figures, warts and all. George Eliot explores this tension in her two long fictions about early-modern prophets, Romola (1863) and The Spanish Gypsy (1867), both of which turn the misfit between individual characters and the types to which they aspire into a driving energy of narrative. Conversely, the Victorian Jesus novel reveals how the tropes of historical realism could be deployed to affirm a religious founder’s singular theological status, as novelists like Wallace used realistic description to set certain moments of spiritual encounter apart from the recurring patterns of religious history.

By exploring these shifting alignments of specialness, typicality, and particularity, we can ultimately gain a broader perspective on the vexed place of comparativism within secularist thinking. Comparative scholarship is often portrayed as the scholarly wing of aggressive Western universalism; critics such as Tomoko Masuzawa have leveled at comparative religion the same charge that is often directed toward comparative literature—that it reduces a world of complex differences to a set of knowable homologies and types available to the secular metropolitan intellectual. But the tensions found in and around the Victorian Jesus novel suggest how comparativism, secular realism, and the religious imagination have several possible relationships. Indeed, Western secularism itself turns out to be torn between its desire to celebrate the mundane minutiae of history and its impulse to assign them equivalent or comparative dignity. If a certain strain of Anglo-American secularism seeks to affirm the everyday or the “typical,” then typicality itself can mean a number of different things, from the idiosyncratic to the generic and replaceable. Tracing these competing projects within nineteenth-century religious studies, I argue, allows us to imagine how there might be different uses for comparative types, secular and otherwise. Continue reading …

In this essay Sebastian Lecourt uses the overlapping cases of Victorian comparative religion and the Victorian Jesus novel to explore the vexed function of comparative types in nineteenth-century writing. Where Victorian comparative religion, with its concept of the generic founder type, had a surprisingly hard time validating the lives of particular individuals, evangelical Jesus novels were able to make use of historical realism in a way that standard portraits of the novel as a secularizing genre seldom anticipate.

SEBASTIAN LECOURT is an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Houston. He is the author of Cultivating Belief: Victorian Anthropology, Liberal Aesthetics, and the Secular Imagination (Oxford, 2018) as well as essays in PMLA, Victorian Studies, b2o, Literature Compass, and Victorian Literature and Culture.

SEBASTIAN LECOURT is an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Houston. He is the author of Cultivating Belief: Victorian Anthropology, Liberal Aesthetics, and the Secular Imagination (Oxford, 2018) as well as essays in PMLA, Victorian Studies, b2o, Literature Compass, and Victorian Literature and Culture.

A roundtable of international scholars considers the work of Sukanya Banerjee on the occasion of her recent addition to the UC Berkeley English Department. Professor Banerjee’s 2018 Victorian Literature and Culture essay “Transimperial” will serve as the touchstone for a discussion ranging across the various topics and fields addressed in her recent work.

A roundtable of international scholars considers the work of Sukanya Banerjee on the occasion of her recent addition to the UC Berkeley English Department. Professor Banerjee’s 2018 Victorian Literature and Culture essay “Transimperial” will serve as the touchstone for a discussion ranging across the various topics and fields addressed in her recent work.

One curious feature of nineteenth-century British and American novels about Jesus is the fact that their central figure often remains largely offstage. In Harriet Martineau’s Traditions of Palestine (1830), William Ware’s Julian; or, Scenes in Judea (1841), Edwin A. Abbott’s Philochristus: Memoirs of a Disciple of the Lord (1878), Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880), James Freeman Clarke’s The Legend of Thomas Didymus: The Jewish Skeptic (1881), Marie Corelli’s Barabbas (1893), and Florence Morse Kingsley’s Titus, a Comrade of the Cross (1894), Jesus is pushed into the background while the narrative follows the life of a minor historical figure or the cultural milieu of first-century Palestine. Ware builds an elaborate character system out of various bit players from the canonical Gospels, turning Barabbas, the robber who is pardoned unwittingly in Jesus’s place, into Mary Magdalene’s ne’er-do-well brother and a proxy for her own narrative arc. Kingsley, beating Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) to the punch, forges a comic subplot out of the story of a cripple whom Jesus robs of employment: “Ha, fellow! thou didst heal me, three years ago, of the palsy, which had withered my limbs; and in so doing took away my living, for my begging no longer brought me money.” And behind all of this are elaborate historical backdrops drawn from both secular historiography and Holy Land tourist guidebooks.

One curious feature of nineteenth-century British and American novels about Jesus is the fact that their central figure often remains largely offstage. In Harriet Martineau’s Traditions of Palestine (1830), William Ware’s Julian; or, Scenes in Judea (1841), Edwin A. Abbott’s Philochristus: Memoirs of a Disciple of the Lord (1878), Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880), James Freeman Clarke’s The Legend of Thomas Didymus: The Jewish Skeptic (1881), Marie Corelli’s Barabbas (1893), and Florence Morse Kingsley’s Titus, a Comrade of the Cross (1894), Jesus is pushed into the background while the narrative follows the life of a minor historical figure or the cultural milieu of first-century Palestine. Ware builds an elaborate character system out of various bit players from the canonical Gospels, turning Barabbas, the robber who is pardoned unwittingly in Jesus’s place, into Mary Magdalene’s ne’er-do-well brother and a proxy for her own narrative arc. Kingsley, beating Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) to the punch, forges a comic subplot out of the story of a cripple whom Jesus robs of employment: “Ha, fellow! thou didst heal me, three years ago, of the palsy, which had withered my limbs; and in so doing took away my living, for my begging no longer brought me money.” And behind all of this are elaborate historical backdrops drawn from both secular historiography and Holy Land tourist guidebooks. SEBASTIAN LECOURT

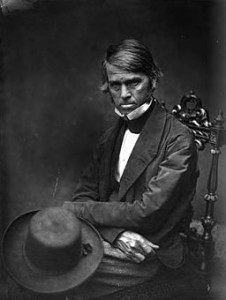

SEBASTIAN LECOURT If, for Henry David Thoreau, “hospitality is the art of keeping you at the greatest distance,” then no one was more hospitable than Thomas Carlyle; after all, Carlyle’s ability to keep his friends at a distance was no less than his ability to keep them. Nothing Americans might think, after the publication of his Latter-Day Pamphlets in 1850, could heal over the wound they felt straightaway that Carlyle “mocked the admiration” he lived to gain and that, for all the gratitude he had toward us, he also, says Henry James Sr., “hated us.” There may have been “an inexplicable rapport,” writes Walt Whitman, between himself and Carlyle, but, judging by Carlyle’s anti-egalitarianism, bigotry, and scorn of democracy, Whitman was “certainly at a loss to account for it.” Who could excuse, and in any case who could deny, the harmful effect of Carlyle’s contempt for abolitionism, suffrage, and social reform? He “stands for slavery,” Ralph Waldo Emerson writes; he “goes for murder, money, capital punishment” and is as “dangerous as a madman. Nobody knows what he will say next or whom he will strike.” Apparently, vegetarianism bothered him. If you praised republics, he liked Russian czars. If you urged free trade, he remembered he was a monopolist. “Cease to brag to me,” says Carlyle, “of America and its model of institutions and constitutions…. They have begotten, with a rapidity beyond recorded example, Eighteen Millions of the greatest bores.” The press describes his work “On Heroes”—his attempt to substitute a new “hero-archy” for lost hierarchies in society and government—as a recipe for “unadulterated despotism” and “more especially how to catch masses of people and indoctrinate them with the feeling of obedience.” When we read his essay “Dr. Francia,” an apology for the supreme dictator of Paraguay, it is not hard to see why, by the 1930s, Carlyle’s theory of the hero seemed compatible with German fascism or that essays from that time, including “Carlyle Rules the Reich,” suggest that Hitler’s own belief in his “fulfillment of duty” to the majorities could “be expressed in familiar old phrases from Carlyle.” In 1945, when Joseph Goebbels tried to dispel Hitler’s sense of defeat, he read to him from Carlyle’s book on Frederick the Great–Hitler’s favorite book.

If, for Henry David Thoreau, “hospitality is the art of keeping you at the greatest distance,” then no one was more hospitable than Thomas Carlyle; after all, Carlyle’s ability to keep his friends at a distance was no less than his ability to keep them. Nothing Americans might think, after the publication of his Latter-Day Pamphlets in 1850, could heal over the wound they felt straightaway that Carlyle “mocked the admiration” he lived to gain and that, for all the gratitude he had toward us, he also, says Henry James Sr., “hated us.” There may have been “an inexplicable rapport,” writes Walt Whitman, between himself and Carlyle, but, judging by Carlyle’s anti-egalitarianism, bigotry, and scorn of democracy, Whitman was “certainly at a loss to account for it.” Who could excuse, and in any case who could deny, the harmful effect of Carlyle’s contempt for abolitionism, suffrage, and social reform? He “stands for slavery,” Ralph Waldo Emerson writes; he “goes for murder, money, capital punishment” and is as “dangerous as a madman. Nobody knows what he will say next or whom he will strike.” Apparently, vegetarianism bothered him. If you praised republics, he liked Russian czars. If you urged free trade, he remembered he was a monopolist. “Cease to brag to me,” says Carlyle, “of America and its model of institutions and constitutions…. They have begotten, with a rapidity beyond recorded example, Eighteen Millions of the greatest bores.” The press describes his work “On Heroes”—his attempt to substitute a new “hero-archy” for lost hierarchies in society and government—as a recipe for “unadulterated despotism” and “more especially how to catch masses of people and indoctrinate them with the feeling of obedience.” When we read his essay “Dr. Francia,” an apology for the supreme dictator of Paraguay, it is not hard to see why, by the 1930s, Carlyle’s theory of the hero seemed compatible with German fascism or that essays from that time, including “Carlyle Rules the Reich,” suggest that Hitler’s own belief in his “fulfillment of duty” to the majorities could “be expressed in familiar old phrases from Carlyle.” In 1945, when Joseph Goebbels tried to dispel Hitler’s sense of defeat, he read to him from Carlyle’s book on Frederick the Great–Hitler’s favorite book.