by Nouri Gana

The essay begins:

On December 17, 2010, the Tunisian public was gripped by a horrific act that I will qualify as a melancholy act. A young street vendor, Mohammad Bouazizi, set himself ablaze in front of the municipal headquarters of Sidi Bouzid, southern Tunisia, following his alleged humiliation by a local policewoman, who not only fined him and confiscated his cart but also slapped him, spat in his face, and insulted his dead father. While terribly tragic, Bouazizi’s act proved, retrospectively at least, somewhat empowering: it sparked what would become a nationwide wave of contention and protest whose ripple effects would then reach Egypt, Libya, Yemen, and Syria (among several other countries not only in the Arab world but also in the world at large, where demonstrations against dictatorships and the neoliberal dispensation took place).

Bouazizi’s act, which also gave rise to several copycat self-immolations across North Africa, is reminiscent of many instances in the Arab world where suicide has served for some as the only means left for communicating their rage and disgust and for protesting against injustices of various kinds. These instances have ranged from the infamous suicide bombings in Palestine, Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere in the Arab world to the very shocking suicide of the modernist Lebanese poet Khalil Hawi, who shot himself to death on June 6, 1982, to protest against the Israeli invasion of Beirut that same day.

The ideological motives and empowering or disempowering effects of these suicides (not just in the sense of autosacrifices but also of heterosacrifices or martyrdoms, as in the case of Palestinians living under the iron-fisted system of Israeli Occupation) remain debatable and vary from case to case. But there is ample evidence, I argue, that they are individual materializations of a more collective or group disposition toward melancholia, on the one hand, as a psychoaffective response to the ever-deepening crisis of the postcolonial project of Arab nationalism and, on the other, as a desperate or despairing response to the unyielding hegemony of the joined-up forces of local despotism and global imperialism. Regardless of their variably distinct individual or ideological character, these suicide protests are nurtured by the affect that occasions them, ranging from the circumstantial shaming of a single person to the historical shaming of entire peoples or collectivities, which is what colonialism constitutes from a deep or surface psychic and cognitive perspective. The interconnections between individual and collective responses to acts of shaming cannot be overstressed: while Bouazizi’s case illustrates how personal shame results in collective identifications and mass protests, Hawi’s case demonstrates how the Israeli invasion of Lebanon as an act of colonial aggression is privatized and decried at the personal level of one individual poet and Arab subject.

Given the continuities between settler colonialism, neocolonialism, and authoritarianism in the Arab world, there is no logical, much less historical, disconnect between Hawi’s and Bouazizi’s suicides. Both are embodiments, or graphic materializations, of a morbid affective disposition that is equally outraged by colonial and national acts of aggression and shaming. It may be the case that both suicides are, from a Lacanian perspective, the tragic testaments to the conscious assumptions of the unconscious death drive—not to say modes of self-realization in the face of the “subjective impasses” generated by the collusion of authoritarianism and colonialism in Tunisia and Lebanon—except that they are, from a historical perspective, unequivocal indictments of both authoritarianism and Zionism. Insofar as shame is variably embedded in colonial and postcolonial societies—instilled and felt at both the individual and collective levels—there will always exist a psychoaffective response that runs along the spectrum of melancholia from depression and self-loathing to reactionary rage and regressive or assertive narcissism. The loss of national sovereignty and individual self-regard may be embodied and substituted by an ideology or a leader, or displaced by cultural forms of artistic creativity that aim in various ways at the recovery of or from lost sovereignty.

Bouazizi’s act does not then so much constitute a melancholy turn as a return to the morbidly traumatic legacy of the June 1967 Six-Day War, in which Israel singlehandedly defeated and shamed the Arab armies of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan and expanded its territory to the West Bank and East Jerusalem, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai Desert (now returned to Egypt in the wake of the 1978 Camp David Accords). While the events of 1967 have routinely been used in the social sciences as an analytical lens through/against which to read the Arab Muslim world (in the very same manner that notions of Islam or “the Arab woman” have previously offered Orientalists indispensable categories of analysis), they have rarely been studied as an object of analysis per se, much less through the combined lenses of postcolonial theory and psychoanalysis. In this respect, the late George Tarabishi’s 1991 book, Al-Muthaqqafūn al-Arab wa-Turāth (Arab intellectuals and tradition), is a salutary undertaking—really, an exception to the generalized reluctance, if not resistance, by Arab intellectuals to discern the psychoaffective legacy of 1967 through the productive lenses of psychoanalysis (in favor of generally Marxist and historicist methodologies).

For Tarabishi, the 1967 defeat resulted in “a psychic epidemic or wabā’ nafsī” that poisoned the affective map of the Arab psyche and resulted in a “pathological effect on Arab subjectivity [maf‘ūl mumriḍ ‘alā al-shakhsiyya al-‘arabiyya].” The subtitle of Tarabishi’s book is Al-taḥlīl al-nafsī li‘usāb jamā‘ī (The psychoanalysis of a collective neurosis); as such, it offers a symptomatic reading of Arab thought in the aftermath of the 1967 military defeat, foregrounding the psychoaffective dynamics of which it was a product. For Tarabishi, while the sudden 1798 colonial encounter with European modernity (Napoleon in Egypt) had resulted in a productive shock that impelled Arabs to start the process of modernization (the so-called nahḍa, or Renaissance), the 1967 defeat resulted in a counterproductive trauma. This trauma compelled Arabs to look backward to the protective shield of tradition, a move that ran against the opening and openness to European modernity that the nahḍa had enacted. In other words, the 1967 defeat compelled Arab intellectuals to turn away from the nahḍa rather than return to it. Disowning the nahḍa, which had opened the region up to European modernity, and reclaiming early Islamic tradition became synonymous with the effort to regain cultural identity and national sovereignty.

This disowning and reclaiming became, according to Tarabishi, all the more pronounced as Israel’s phallic omnipotence (symbolized by the superiority of its air force) was seen to neutralize Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser and his power as a protective father figure. With the demise of that towering figure, Arabs, for Tarabishi, found in the return to turāth (tradition) an alternative or compensatory symbolic father. While the nahḍa was dominated by the searing sense of belatedness and the urge to catch up with Europe, the naksa (setback) of 1967 was dominated by the shame of castration and the impulse to act out, react, repair, or compensate for the traumatic losses incurred in the war. The 1967 defeat was traumatic, according to Tarabishi, not only because of its utter unexpectedness (at a time when victory over Israel was thought to be only a matter of time) but also because of its humiliating decisiveness and recursive aftereffects—aftereffects that still reverberate in Arab contemporaneity and that can best be illustrated by the dawning realization that victory over Israel has become as impossible as protection from its aggression. It’s as if the defeat had catapulted or expelled Arabs out of history at the very moment when they were reentering it with the ideology of Arab nationalism and the success of anticolonial movements (especially in Algeria). These nationalist and anticolonial movements have become exemplars of a third-worldist and nonalignment imagination. The symbolic victory of Nasser in 1956, which had engendered feelings of euphoria and good omens at the time, must have made it even harder to stomach the subsequent trauma of the 1967 defeat. Its untimeliness was too much to bear at a moment of high expectations for renewed Arab glory, which is why, for Tarabishi, it resulted in many regressive psychopathological practices.

The defeat of 1967 was, then, the beginning of an end that would later be gradually, but steadily, hammered home by a series of events ranging from the Camp David Accords to those in Oslo, up to the by-now routine Israeli onslaughts on Gaza. The finality of the defeat was such that it foreclosed the possibility of a second round. What is traumatic is not so much the defeat in itself, but the afteraffect in which it was and continues to be experienced and relived as an irreversible destiny—as a continually retraumatizing re-memory and reenactment of the foreclosure of a possible future, or worse, the foreclosure of the very possibility of a future. In other words, the defeat has left Arabs bereft of a dignified, let alone promissory, future, and, what is even more damaging, it has left Arabs with a sense that their past achievements (Arab Islamic glory and high nationalism) are actually the best they could ever have aspired to or achieved. Arab contemporaneity has become from this perspective unlivable unless it is imagined as a future anchored in a glorious Muslim past—“a future past,” to borrow David Scott’s felicitous expression.

Arab contemporaneity is then stranded, or suspended, in a present without potentiality, an impasse of individual dignity and national sovereignty. The severity of the defeat—its irrevocable verdict—matches only the cruelty with which it remained inassimilable to the Arab psyche. The very fact that the defeat is called a naksa or setback speaks volumes about the ways in which it had already been displaced and disavowed rather than reckoned with and worked through. Yet, the issue may not be with accepting defeat, much less with working through shame, but with giving up the struggle against the joined forces of local despotism and settler colonialism. Accepting defeat in the Freudian sense of mourning would amount to accepting the verdict of reality (Israeli superiority) and the injunction to mourn the lost object (sovereignty and dignity). The reverse amounts to the unyielding determination, or stubborn fixation in psychoanalytic terms, on recovering what is lost and redressing the colonial past of injustice and transgression. Indeed, Bouazizi’s suicidal protest and the various uprisings that followed suit suggest that the 1967 defeat has not been assimilated by the Arab psyche precisely because it continues to be contested locally through what I have been calling melancholy acts. While Slavoj Žižek contends in a recent article that melancholia has become the norm that must be subverted, I argue that in the Arab world melancholy acts of this sort are indeed ethical acts not only because of their fidelity to lost objects or lost causes but also because they dissent from the normative structures of mourning, which are in the Arab world aligned with the system of global imperialism and settler colonialism. There is a clear continuity between Hawi’s and Bouazizi’s suicides, just as there is a continuity between resisting authoritarianism nationally (Bouazizi) and colonialism transnationally (Hawi). The question for me henceforth, though, is not so much how suicide protests spark popular revolutions or at least public contentions, but how popular revolutions sparked by suicide protests are materializations of a cultural and critical capital that has largely been determined by a collective disposition toward melancholia.

There is of course nothing strikingly strange (or familiar for that matter) from a psychoanalytic viewpoint about the surety and reliability of the nexus I am trying to establish here between melancholia and militancy. It is already there in Freud’s “The Ego and the Id,” and it is especially articulated in Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. Toward the end of The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon overturns Freud’s conception of pathological and autodestructive melancholia and states that the French psychiatrists in Algeria “were accustomed when dealing with a patient subject to melancholia to fear that he would commit suicide. Now the melancholic Algerian takes to killing. The illness of the moral consciousness, which is always accompanied by auto-accusation and auto-destructive tendencies, took on in the case of Algerians hetero-destructive forms. The melancholic Algerian does not commit suicide. He kills.” Fanon does not theorize further this hetero-destructive disposition of colonial melancholia (which he also calls “pseudo-melancholia”) and does not actually worry that much, since, in the colonial context, everything, including psychic pathologies, would be mobilized for the purpose of decolonization in the very same manner that psychoanalysis, and more so psychiatry, were mobilized by the French colonial administration in the service of colonization. At any rate, the dynamic relationship between melancholia (regardless of its pathological component) and decolonial resistance in the decades following WWII were very much in the air and well established, such that by the time Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari published their Anti-Oedipus, Michel Foucault could gibe in the preface to the American translation of the book, perhaps in a fit of impatience and frustration: “Do not think that one has to be sad in order to be militant.”

The longer project from which this article is extracted seeks to probe the concept of melancholia in psychoanalytic and postcolonial thought in order to illuminate its far-reaching relevance to an Arab decolonial critique of colonialism and neocolonialism alike. Because of space constraints here, I will not engage in detailed analyses of the literary examples I intend to make use of as illustrations. Instead, I will cite short statements and dictums and at times even aphorisms in order to first hammer home what I mean by “melancholy acts” and then show how these “melancholy acts” do indeed serve as acts of decolonial critique. If, as Edward Said argues, Arabic literary writing became “a historical act” in the aftermath of 1948 and, “according to the Egyptian literary critic Ghali Shukri, after 1967, an act of resistance,” my aim herein is to inquire about the psychoaffective apparatus, force, or disposition that must have sustained the production of literature as a resistant and dissident act.

By “a melancholy act,” I mean to describe, insofar as the literary examples are concerned, the manifestation or materialization in language of the melancholic after-naksa-affect whose illocutionary and agentive force registers no less than an act of refusal of forgetful mourning practices and a demand for justice and redress. It is my contention that melancholia’s underappreciated dissent from normative structures of mourning is a threshold moment of critical and cultural empowerment in colonial and postcolonial societies, namely, in the Arab world, where the nexus between proxy and settler colonialisms continues to produce and reproduce almost all aspects of literature and culture. In this sense, Enzo Traverso’s postulation that “melancholic critique is the condition of all critical thinking,” is nowhere more relevant than in the context of the Arab world where this melancholy condition of critical thinking is compounded by the litany of wars and military defeats that mark modern Arab history. The various literary and cultural examples I engage with make legible—at the level of language, imagery, and rhetoric—the legitimacy of Arab political grievances and the continuity Arab artists have established between resisting authoritarianism at home and fighting colonialism abroad. Continue reading …

This essay discusses the politics of affect in post-1967 Arabic literary and cultural production. It argues that melancholia’s underappreciated swerve from normative structures of power and mourning is a threshold moment of critical and cultural enablement in the Arab world, where the nexus between proxy and settler colonialisms continues to produce and reproduce almost all aspects of literature and culture.

NOURI GANA is Professor of Comparative Literature and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is the author of Signifying Loss: Toward a Poetics of Narrative Mourning and the editor of The Making of the Tunisian Revolution: Contexts, Architects, Prospects and of The Edinburgh Companion to the Arab Novel in English. He is currently completing a book manuscript on the politics of melancholia in the Arab world and another on the history of cultural dissent in colonial and postcolonial Tunisia.

NOURI GANA is Professor of Comparative Literature and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is the author of Signifying Loss: Toward a Poetics of Narrative Mourning and the editor of The Making of the Tunisian Revolution: Contexts, Architects, Prospects and of The Edinburgh Companion to the Arab Novel in English. He is currently completing a book manuscript on the politics of melancholia in the Arab world and another on the history of cultural dissent in colonial and postcolonial Tunisia.

NOURI GANA

NOURI GANA This lecture is drawn from Rey Chow’s chapter in the anthology

This lecture is drawn from Rey Chow’s chapter in the anthology  In

In

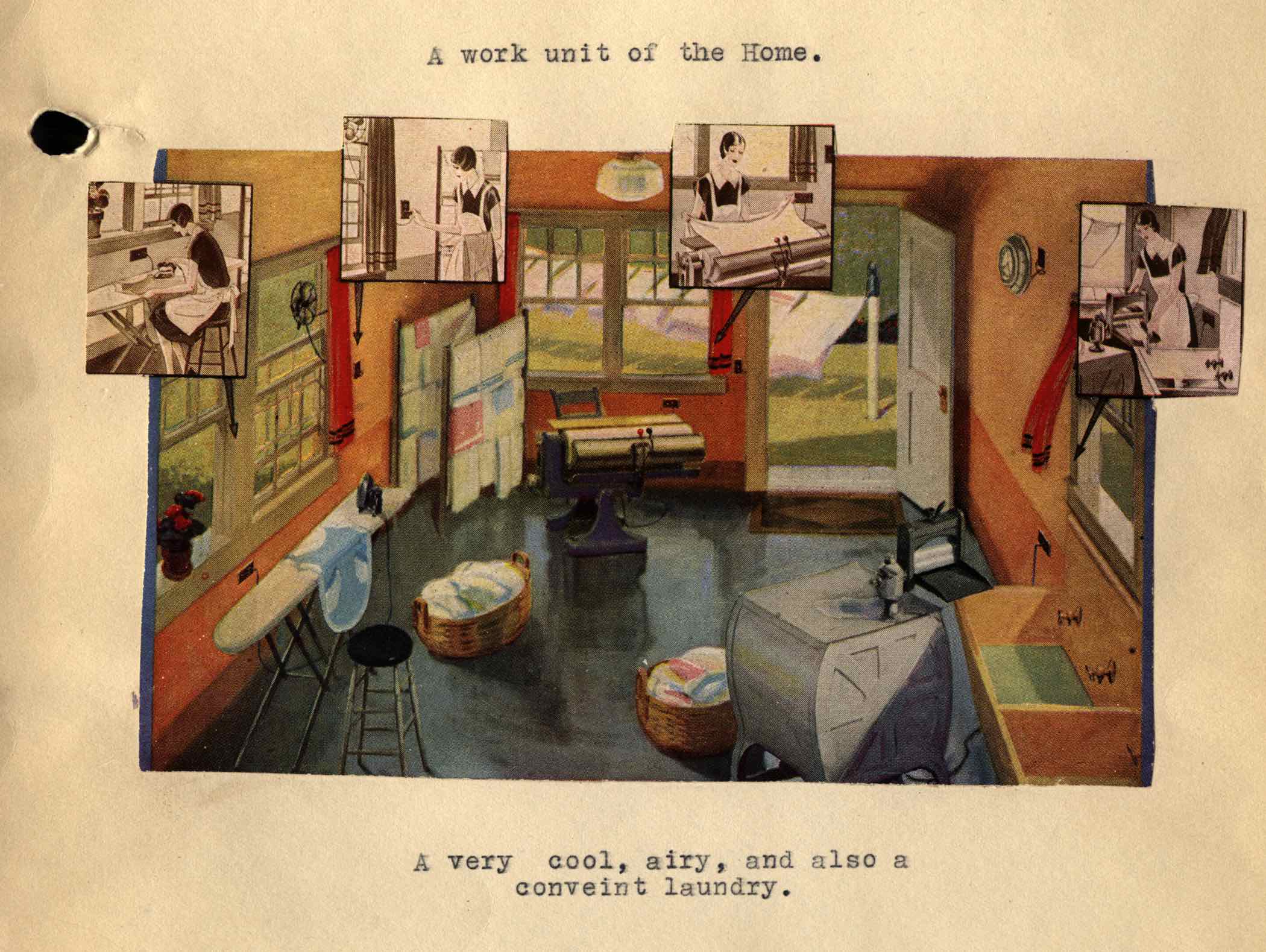

ANDREW M. SHANKEN

ANDREW M. SHANKEN