In recognition of the impact of Covid-19 on campus instruction and the rise of unplanned distance learning, UC Press is pleased to make Representations and all of its online journals content free to all through June 2020.

The Lower Criticism

by Mark Taylor

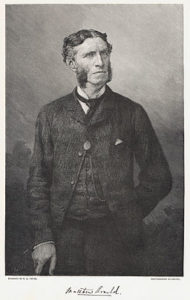

In this essay Mark Taylor reassesses Matthew Arnold’s place in the history of modern criticism, arguing that his most important contribution to that history was his refashioning of the critic as an empty and recessive type of agent. Arnold’s famous call for criticism to abandon the “sphere of practical life” was no mere slogan, but the product of an extended meditation on the nature of agency and action, undertaken in dialogue with the works of the philosopher Benedict de Spinoza. From Spinoza’s “lower” criticism, Arnold derived a method that both approaches individual texts as actions and stresses the critic’s role in “composing” those texts as individuals in the first place. To perform these functions, however, criticism must renounce its claim to count as an action in its own right. The essay traces the development of this method from Arnold’s early essays on Spinoza through his mature criticism of the 1860s and 70s and considers its bearing on the wide variety of practices that describe themselves as “critical” today.

In this essay Mark Taylor reassesses Matthew Arnold’s place in the history of modern criticism, arguing that his most important contribution to that history was his refashioning of the critic as an empty and recessive type of agent. Arnold’s famous call for criticism to abandon the “sphere of practical life” was no mere slogan, but the product of an extended meditation on the nature of agency and action, undertaken in dialogue with the works of the philosopher Benedict de Spinoza. From Spinoza’s “lower” criticism, Arnold derived a method that both approaches individual texts as actions and stresses the critic’s role in “composing” those texts as individuals in the first place. To perform these functions, however, criticism must renounce its claim to count as an action in its own right. The essay traces the development of this method from Arnold’s early essays on Spinoza through his mature criticism of the 1860s and 70s and considers its bearing on the wide variety of practices that describe themselves as “critical” today.

The essay begins:

“down late. bad morning, and did little. read in D. Laertius & Goethe’s Poems. After dinner walked alone to Brathay churchyard and sate there till dark. read Spinoza. after tea, cards & chess. Spinoza again—began letter to F. L. S. Augustine’s letters & so to bed. Thorough bad day and could never collect myself at all.”

—Matthew Arnold, diary entry, Saturday, January 4, 1851

In the two years following this diary entry, the young Matthew Arnold appears to have discovered some remedy for the debilitating condition of an uncollected self. In 1853, Arnold published Poems: A New Edition—his third volume of verse and the first to appear under his own name—accompanied by a short critical Preface that stands out for the confidence of its practice of collection. Arnold’s purpose in the Preface is to justify his decision to omit the long dramatic poem “Empedocles on Etna” from the 1853 volume, but in doing so he is led to consider the nature of poetry and poetic value in general. “What are the eternal objects of Poetry, among all nations and at all times?” he asks—and answers, “They are actions; human actions; possessing an inherent interest in themselves, and which are to be communicated in an interesting manner by the art of the Poet.” It’s on this basis that “Empedocles” must be excluded: its hero’s situation is one “in which suffering finds no vent in action,” and from which, therefore, no properly “poetical enjoyment” can be derived.

Many critics have observed that this definition of poetry echoes Aristotle, whose “admirable treatise” the Poetics defines tragedy as “a representation not of persons but of action and life.” But the sources of the Preface are neoclassical as well as classical, and Arnold here gives the Aristotelian formula a Goethean twist. In his 1827 essay on the Poetics, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe famously rejects Aristotle’s focus on the effects of tragedy, arguing instead that tragedy’s essence resides in its “structure.” More than an imitation of action—reproducing, and thereby expunging, the associated feelings of fear, terror, and pity in the minds of its spectators—tragedy for Goethe is an action in its own right, whereby the poet incorporates these tragic feelings into the structure of the work, resolving them into a “unified whole.” All poetry, in fact, is defined by the production of this aesthetic unity, and the poet by the agency of producing it—what Goethe elsewhere calls “Architectonicè,” or, in Arnold’s own rendering, that “power of execution, which creates, forms, and constitutes.” The Preface thus oscillates between two distinct (and not obviously compatible) conceptions of poetic form, each of which implies a slightly different account of why “Empedocles on Etna” cannot be included in a collection entitled Poems. From one perspective, “Empedocles” is “poetically faulty” because its hero fails to act: his despair is “unrelieved by incident, hope or resistance.” But from the other, the failure is Arnold’s: to carry out, that is, the work of creation and formation that together constitute the action of poetry. If Arnold hoped that writing the Preface would (to quote his Empedocles) “cut his oscillations short,” then it too must be considered a failure.

But the Preface is also Arnold’s inaugural effort as a critic—as if the process of reflecting on the relationship between poetry and action had led him to attempt a new kind of action in his own writing. What kind of action, then, is criticism, if indeed it is an action at all? This is the question I will attempt to answer in this essay—an essay that is itself a work of criticism, and thus derives its identity and its agency in part from Arnold’s example. Although, as I will show, Arnold retains the 1853 Preface’s commitment to treating literary texts as actions of a particular kind, his evolving critical program increasingly complicates any attempt to define criticism itself as an action, or the critic as an agent in any ordinary sense of that word. For Arnold, I argue, criticism’s refusal to be action is what enables it to fulfill one of its fundamental functions: recognizing and defining other texts as actions or—what comes to the same thing—as forms.

In this essay, I locate the source of this conception of criticism not in Aristotle or Goethe, but in the work of Goethe’s teacher, Benedict de Spinoza—in whose “positive and vivifying atmosphere” Arnold’s “Empedocles” was composed. Uncovering the Spinozist roots of Arnoldian criticism not only enriches our understanding of Arnold’s enduring influence on the humanities today, in particular on the variety of practices, distributed widely across disciplines and institutions, that describe themselves as “criticism”; it also helps us to see more clearly the stakes and significance of that self-description. Underlying the whole history of modern criticism, that is—from declarations of the critic’s purposes and procedures to debates about what is and is not “critical,” or, more recently, “postcritical”—is a fundamentally Arnoldian constellation of questions about agency, action, and value. For Arnold, an important part of Spinozism’s appeal was its usefulness for his career-spanning struggle against Benthamite utilitarianism. Alike in their identification of action and existence—of “being” and “doing”—Spinoza and Jeremy Bentham developed quite different accounts of what it means to act, to be an agent, and to determine the value of an action. Where Bentham and his followers adopted a relativist conception of value, seeing it as wholly determined by particular, highly structured social contexts, Spinozism appealed to Arnold because it retained a commitment to absolute value guaranteed by God. And, just as Spinoza devised a method for interpreting sacred texts in order to clear away false and superstitious misconceptions about God, so too did Arnold offer criticism as a means of preserving and preparing for an absolute value—the best that has been thought and said—that could never be wholly realized.

As this essay will show, Arnold followed Spinoza in securing criticism’s absolutes by abandoning (as he famously put it in “The Function of Criticism at the Present Time”) the “sphere of practical life.” This, I argue, is the meaning of the much-discussed vagueness of Arnoldian criticism’s central categories, including “sweetness and light,” “the best self,” “the grand style,” and, preeminently, “culture” itself. The Arnoldian critic, too, “avails himself” of this “indefiniteness” (as the philosopher Henry Sidgwick accused Arnold of doing), becoming a strangely recessive, even self-canceling kind of agent, emblematized by Arnold’s own pervasive but empty presence in Victorian public culture. In contrast to recent efforts to historicize criticism in terms of a heroic paradigm of critical action, I argue here that criticism, to the extent that it relies on Arnold as a “touchstone,” is organized discursively around the recession or decline of agency. This organization is often unconscious, or even explicitly disavowed, and many critics (including, sometimes, Arnold himself) claim a “stronger” and more active version of agency in their work. I have therefore borrowed a term usually applied to Spinoza’s writings on scriptural interpretation to designate the particular account of agency and action Arnold and Spinoza share: both are practitioners of what I will call the lower criticism.

In biblical scholarship, the “lower” is usually contrasted with the “higher” or “historical” criticism. In broadest terms, the higher criticism approaches scripture as a text created by human beings, for human reasons, at a particular historical time, and is therefore concerned with historical context (authorship, time and place of composition, sources, and so on), while the lower or textual criticism focuses on the text itself and its internal evidence, often with a view to establishing an authoritative version from multiple textual variants. As the authors of the Handbook of Biblical Criticism observe, the term is falling into disuse, “because of its pejorative sound coupled with the increasing acknowledgment that textual criticism is both important and complex.” But it is precisely this pejorative sense that I wish to emphasize. If Arnold was the first to pose the perennial question of the “function” of criticism, he also ensured that all attempts to answer it would inevitably fall short. Since, for Arnold, criticism is defined equally by its treatment of texts as actions and by its own recessive refusal to be action, to speak of criticism’s “function” (that is, what it “does” in a given social and historical context) is to inhabit a paradox. To many subsequent critics, this paradox has seemed evidence of Arnold’s intellectual sloppiness, or—worse—of the ideological subterfuge whereby the refusal of power masks subtler forms of domination. In this essay, however, I argue that Spinoza’s philosophy suggests a different, less suspicious interpretation of the Arnoldian paradox and of its enduring importance for the countless critics (from T. S. Eliot to Virginia Jackson) who have produced their own variations on the formula“The Function of Criticism at the Present Time.” Continue reading …

MARK TAYLOR is a Lecturer in English and Coordinator of the Public Humanities Initiative at Stanford University.

MARK TAYLOR is a Lecturer in English and Coordinator of the Public Humanities Initiative at Stanford University.

In the French National Archives, there is a foot-high folder comprising fin de siècle surveillance reports concerning foreign revolutionary activity on French soil. It contains only one photograph, which shows a woman with dark, chin-length hair, positioned outdoors on an expanse of cobblestone, near a window covered by metal bars. She stands with one hand on the back of a wooden chair and the other on her hip. She wears a black, feathered straw hat and a bolero jacket with decorative trim—an outfit, in the words of the accompanying police report, that “left a little to be desired.” As with many old photographic portraits that required protracted stillness from their subjects, the woman’s expression is difficult to discern, though she does appear to be smiling slightly. On the thick card stock of the photograph’s reverse is a label: “Nihiliste russe arrêtée le 24 septembre à Toulouse” (Russian nihilist arrested September 24 in Toulouse).

In the French National Archives, there is a foot-high folder comprising fin de siècle surveillance reports concerning foreign revolutionary activity on French soil. It contains only one photograph, which shows a woman with dark, chin-length hair, positioned outdoors on an expanse of cobblestone, near a window covered by metal bars. She stands with one hand on the back of a wooden chair and the other on her hip. She wears a black, feathered straw hat and a bolero jacket with decorative trim—an outfit, in the words of the accompanying police report, that “left a little to be desired.” As with many old photographic portraits that required protracted stillness from their subjects, the woman’s expression is difficult to discern, though she does appear to be smiling slightly. On the thick card stock of the photograph’s reverse is a label: “Nihiliste russe arrêtée le 24 septembre à Toulouse” (Russian nihilist arrested September 24 in Toulouse).