Cuban Corals in East Berlin’s Natural History Museum, 1967–74

by Manuela Bauche

The essay begins:

On October 7, 1974, the German Democratic Republic (GDR) turned twenty-five. Among the events commemorating this anniversary was a temporary exhibition that opened within East Berlin’s Natural History Museum, the Museum für Naturkunde. The show, entitled Forschung im Museum (Research at the museum), aimed to give an overview of the diversity of research conducted at the GDR’s most important natural history museum during the first quarter-century of the republic’s existence. Included was an impressive exhibit: a coral-reef diorama. The exhibition occupied one room on the ground floor of the museum. Depending on which side visitors entered, the diorama would be either the first exhibit they encountered or, after a long row of glass cabinets bearing information and evidence of the museum’s research activities, the last. The diorama’s plain chipboard wall was three meters high and five meters wide. In its center, a glass window invited visitors to peek inside. Within could be seen a submarine landscape: a slope of sand-colored coral rock, which, while slightly rising up toward the surface of the water, disappeared into the depth; ball-like corals with delicately grooved yellowish and brownish surfaces strewn about the sea floor; in the foreground, a group of bright blue fish, all heading in the same direction, eyes seemingly fixed on an invisible goal; and a small black and yellow fish coming toward them. On the lower left, a gaping hole in the rock formation revealed a glimmering blue, foreshadowing deeper waters and allowing yet another fish entrance into the coralline world.

The new exhibit fascinated Berliners. The press praised it as a “gorgeously colorful, lifelike detail of a Cuban bank reef,” at times even omitting the fact that the diorama—made of dried and dead coral specimens, fish casts, plaster, steel, and glass—in fact was a waterless representation of a reef. Indeed, newspapers proudly announced that the Museum für Naturkunde now held “a coral reef with colorful flora and fauna” that showed a “confoundingly colorful life, diverse in terms of both forms and species, in the midst of bizarre coral formations.” But just as fascinating as the diorama itself was the process of its coming into being. Its construction had entailed experimentation with different types of dyes, inventiveness in the face of scarce resources, and, of course, the application of technical skill and patience.

In 1967, even before the construction of the diorama, a team of researchers from Berlin had conducted an ambitious expedition to Cuba to collect corals and make casts of the fish that would form the centerpiece of the exhibit. After an Atlantic crossing of more than nine weeks, two scientists, two preparators from the Museum für Naturkunde, a doctor, and a seaman from the GDR’s Society for Sports and Technology (Gesellschaft für Sport und Technik, GST) reached Havana. With them more than seventy boxes of equipment, several small boats, and a truck were unloaded. There they joined four divers from the GST who had arrived by plane and had already set up an expedition camp on the island’s north shore, seventy kilometers east of Havana, at a spot called Arroyo Bermejo.

The expedition’s aim was to collect enough corals and other specimens from the reef lining the shore to reconstruct a ten-meter-long section in the Museum für Naturkunde’s exhibition. Over the course of three weeks, the GST divers towed a raft to the reef that paralleled the shore at a distance of a few hundred meters, dived into the reef to break corals out of the chalk structure, lifted them to the raft, and delivered them to the expedition camp. The museum staff then scattered the corals on the beach to dry, clean, and gradually pack them into the boxes they had taken care to bring with them from Berlin. In the end, forty-one boxes of approximately six to ten tons of reef material were shipped to the GDR. Seven years later, instead of the envisaged ten-meter-long reconstruction, [a much smaller] diorama . . . was realized.

To understand the significance of the expedition, it must be seen in the context of the diplomatic ties established between Cuba and the GDR in the fields of science and education. In 1962, only three years after the Cuban Revolution, the University of Havana and East Berlin’s Humboldt University had agreed on a joint “Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation” that allowed for a regular and systematic exchange of students, lecturers, scientists, and publications. Beyond this, a number of other points of collaboration were established between scientific institutions in the two countries: in 1966, the “Tropenforschungsinstitut Alexander von Humboldt” (Alexander von Humboldt Tropical Research Institute) was founded as a joint institute of the Cuban and GDR academies of sciences; and, from 1974 on, botanists from the universities of Jena and Berlin and scientists from Havana’s National Botanical Garden worked, in bi-annual expeditions, toward a comprehensive register of Cuba’s flora. The Cuban side had been particularly interested in establishing these kinds of international collaborations, hoping that they would help to build the scientific capacities urgently needed in the newly founded republic. Among the socialist states with which Cuba maintained scientific relations, the GDR ranked second—after the Soviet Union and ahead of Bulgaria. From a GDR perspective, Cuba was an important partner for activities that needed a tropical environment, as it was one of the few tropical socialist countries and thus politically accessible to the East German state.

Looking at the exhibition—in which only a small portion of the material collected ultimately appeared (in the diorama), and then only several years after the trip to Cuba—it is striking that the museum did not feature the idea and practice of socialist friendship more prominently, especially since Cuban divers, too, had taken part in the endeavor. Indeed, the anniversary of the country’s founding might have provided a perfect opportunity to highlight the importance of this political framework. The only hint of the existence of the expedition itself was a map of Cuba, on which the place where the corals had been collected was marked. Apart from this, the exhibition focused solely on educating the public on the biology of corals and the formation of coral reefs, its descriptive panels detailing the museum’s “coral-reef research in Cuba,” in conformance with the exhibition’s overall agenda of presenting examples of the museum’s research. The special Cuban-GDR relation that had provided the foundation for the genesis of the diorama remained invisible.

Why did the Museum für Naturkunde opt to present Cuban corals in this particular manner? What happened to socialist internationalism along the (corals’) way? In their contributions to this Representations forum, Alice Goff and Mario Schulze show that international diplomacy was an important precondition for the transfer of objects across national boundaries, and that both the design and the planning of exhibitions were at times intimately linked to global political realities such as Cold War competition. In what follows, I examine the effect of global politics and diplomacy on both the coral-reef expedition of 1967 and the 1974 display of the diorama that resulted from it. I will show that although bilateral agreements were an important precondition for both projects, informal contacts between players beyond the political field were at least as crucial. I question the assumption that objects that crossed political and state borders during the Cold War for exhibition purposes were always and as a matter of principle intertwined with high-level diplomacy, that they would necessarily carry political meaning or act as “ambassadors” in international relations. Instead, I show that although the appropriation and transfer of objects could not have been accomplished without a diplomatic framework, it could just as easily come about as a result of contacts between players operating beyond the official political field, in this case divers from the GDR and Cuba.

In this way, my account of the history of the coral-reef diorama also departs from the popular depiction of political and cultural life within socialist countries, and of exchange between them, as generally being organized from the top down and rigidly controlled. Instead, I join with current research that argues for a more complex idea of what “socialist friendship” meant on the practical level and shows that transnational exchange between socialist countries at times occurred beyond high-level politics. Continue reading …

This essay reconstructs the history of a coral-reef diorama, the outcome of a German Democratic Republic expedition to Cuba, that was displayed in East Berlin’s Natural History Museum in 1967 on the occasion of the GDR’s twenty-fifth anniversary. The essay investigates how the practice of socialist internationalism influenced the diorama’s coming into being, arguing that while official diplomatic relations between Cuba and the GDR were a prerequisite for the expedition, nongovernmental contacts were central to both the initiation and execution of the project. It also demonstrates how the diorama’s display was informed more by national and institutional concerns than by the rhetoric and policies of internationalism.

MANUELA BAUCHE is a historian and postdoctoral researcher at Berlin’s Natural History Museum. Her research interests lie in the global history of life sciences and scientific expeditions in the twentieth century.

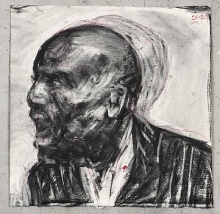

Saba Mahmood, Professor of Anthropology at the University of California at Berkeley, passed away on March 10th, 2018. The cause was pancreatic cancer. Professor Mahmood specialized in Sociocultural Anthropology and was a scholar of modern Egypt. Born in Quetta, Pakistan, in 1962, she came to the United States in 1981 to study architecture and urban planning at the University of Washington in Seattle. She received her PhD in Anthropology from Stanford University in 1998 and taught at the University of Chicago before coming to the University of California at Berkeley in 2004, where she offered her last seminar in fall 2017. At Berkeley, in addition to the Anthropology Department, Professor Mahmood was affiliated with the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, the Program in Critical Theory and the Institute for South Asia Studies (where she was instrumental in creating the Berkeley Pakistan Studies Initiative, the first of its kind in the United States).

Saba Mahmood, Professor of Anthropology at the University of California at Berkeley, passed away on March 10th, 2018. The cause was pancreatic cancer. Professor Mahmood specialized in Sociocultural Anthropology and was a scholar of modern Egypt. Born in Quetta, Pakistan, in 1962, she came to the United States in 1981 to study architecture and urban planning at the University of Washington in Seattle. She received her PhD in Anthropology from Stanford University in 1998 and taught at the University of Chicago before coming to the University of California at Berkeley in 2004, where she offered her last seminar in fall 2017. At Berkeley, in addition to the Anthropology Department, Professor Mahmood was affiliated with the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, the Program in Critical Theory and the Institute for South Asia Studies (where she was instrumental in creating the Berkeley Pakistan Studies Initiative, the first of its kind in the United States).

This volume examines translation from many different angles: it explores how translations change the languages in which they occur, how works introduced from other languages become part of the consciousness of native speakers, and what strategies translators must use to secure acceptance for foreign works.

This volume examines translation from many different angles: it explores how translations change the languages in which they occur, how works introduced from other languages become part of the consciousness of native speakers, and what strategies translators must use to secure acceptance for foreign works.

Alfred Hitchcock’s work is, in our view, antithetical to the idea of fallacy, if we understand by fallacy an error committed against a logical mode of validity, an error that needs to be corrected. How this antithesis plays itself out is consistently fascinating. Indeed, it is deception, the state of mind most readily associated with fallacy, that Hitchcock’s cinema loves to portray. In film after film, the condition of being taken in, of mis-taking a situation for what it actually is, constitutes the mise-en-scène not only in the classical, theatrical sense of a setting for the story but also, more critically, in the metaphysical sense of a dynamic play of terrifying forces, the resolution of which (if there is one) often strikes us as conventional, perfunctory, and inadequate. How Hitchcock constructs and furbishes such mise-en-scènes is the focus of the present essay. Specifically, we will examine how he dramatizes deception as a trajectory of the fallacious—that is, as a scenario with its own logics that are played out within the setting of modern Western society.

Alfred Hitchcock’s work is, in our view, antithetical to the idea of fallacy, if we understand by fallacy an error committed against a logical mode of validity, an error that needs to be corrected. How this antithesis plays itself out is consistently fascinating. Indeed, it is deception, the state of mind most readily associated with fallacy, that Hitchcock’s cinema loves to portray. In film after film, the condition of being taken in, of mis-taking a situation for what it actually is, constitutes the mise-en-scène not only in the classical, theatrical sense of a setting for the story but also, more critically, in the metaphysical sense of a dynamic play of terrifying forces, the resolution of which (if there is one) often strikes us as conventional, perfunctory, and inadequate. How Hitchcock constructs and furbishes such mise-en-scènes is the focus of the present essay. Specifically, we will examine how he dramatizes deception as a trajectory of the fallacious—that is, as a scenario with its own logics that are played out within the setting of modern Western society.