by Helen Deutsch

UCLA’s Helen Deutsch here puts Yale critic and cofounder of the New Criticism William K. Wimsatt into the balance with the most influential poet of eighteenth-century England, Alexander Pope. A scholar-collector with a lifelong penchant for Pope’s poetry and iconography, Wimsatt molds his influential theoretical paradoxes of abstract particularity after the uniquely embodied poet, who made himself inseparable from his art. The elusive power of style connects universal truth to worldly materiality for both writers, giving theoretical abstraction a human likeness.

The essay opens:

William K. Wimsatt with Roubiliac’s busts of Pope at the National Portrait Gallery, 1961. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, London.

I begin with a photo and what first appears to be a visual joke. William K. Wimsatt, New Critical patriarch of the theoretical Yale Critics, stern dispeller of the intentional and affective fallacies, and devotee of the abstract poetic object he deemed the “verbal icon,” looms over a table, upon which are precariously displayed six marble busts of the great eighteenth-century poet Alexander Pope by the poet’s contemporary, the French sculptor Louis-François Roubiliac. The bareheaded and be-mantled neoclassical busts, each varying subtly from the next, join in a contemplatively oblique stare—into the future? the distant past? the eyes of the viewer?—while Wimsatt, modestly positioned at the left edge of the table, gazes straight into the camera. On the wall behind Wimsatt are empty picture hangers, below which are captions: it seems that an exhibit has been taken down and the curator, haunted by his doubled shadow, is preserving one last look. Wimsatt’s is the proud gaze of an avid collector—of stamps, Native American artifacts, and minerals (this last item also a penchant of Pope’s, who festooned the walls of his famous grotto at Twickenham with exotic rocks and curios)—whose convocation of busts was the prize of years of avid pursuit across England of images of the diminutive poet known for his beautiful head and curved spine. These adventures took Wimsatt into the homes of aristocratic families whose ancestors had befriended Pope, where the busts had long proclaimed the owner’s political affiliation and personal distinction. The busts themselves seem to cast white shadows beneath the table, inverting Wimsatt’s dark ones.

Scholars of English literature do not usually imagine Wimsatt, whose authority and influence are legendary for the profession, in such distinctive company. Wimsatt’s polemical essays on the affective and intentional fallacies, written in collaboration with the philosopher Monroe Beardsley, in his classic The Verbal Icon (1954) attempted to wrest poetry from the grip of the author’s biography on the one hand and the reader’s affective response on the other. Criticism for Wimsatt was a science; its mandate was meticulous textual analysis, and its goal was objectivity. His fame, late in his career, as a stern enforcer of the rules was captured in a spoof song, “Big Bad Bill” (to the tune of the popular ballad “Big Bad John”), by his former student Doug Canfield: “Let’s cut out this impressionism / And not make poetry confessionism; / Let’s make the Object the real test: / The Old New Critics are still the best.” What then to make of Wimsatt’s career-long fascination with the first self-supporting professional poet in English literature, a poet who spent his career writing about himself? In the photo’s balance of contraries, Big Bad Bill behind multiple renditions of the man who once called himself the little Alexander whom all the women laugh at, we can locate a different and equally important aspect of Wimsatt’s criticism: the idea of style.

Of all his collections, none was more personal than Wimsatt’s assemblage of images of Pope, put on display in the exhibit recorded in the photograph at London’s National Portrait Gallery in 1961; Wimsatt typed out the catalog himself and included items from his own personal collection. This effort was expanded and commemorated in his monumental 1965 study The Portraits of Alexander Pope, which bears an image of a Roubiliac bust on its cover. In an homage to Wimsatt written shortly after his death in 1975, his Yale colleague René Wellek rightly observes that the Pope catalog “traces the archetypes of the portrait so meticulously that the method can serve as a model for similar investigations into the history of portrait painting and of sculpture.” A substantial addendum to the catalog’s compendium of originals and multiple imitations, which Wimsatt spent twenty-five years researching and which, like all great collections, would never be complete, was published posthumously. Wimsatt’s sustained engagement with Pope as author and image might seem from our current vantage point to contradict his work’s fundamental tenets. Yet while Wimsatt famously, if complexly, defined the work of art as an object free of both authorial intention and the reader’s affective response, he nevertheless gave that object a persistently heavy weight, linking it to the visual and material world by its very definition as icon. The balances of generality and particularity that exemplified the literary text for Wimsatt, specifically the paradoxes of the concrete universal’s detailed abstraction and the verbal icon’s dual status as object and image, are rooted in the age that gave us the professional author and inspired and epitomized by the eighteenth-century poet who made himself inseparable from his art. As ephemeral as Belinda’s lock, yet as weighty as a marble bust, Pope’s poems are at once historically particular, personal, and immediate. Concrete universals with a distinctive human voice, they give ballast to Wimsatt’s theorizing, informing his conceptions of poetry, criticism, and the thing that unites the two—style.

…The enduring presence of Pope across Wimsatt’s scholarly oeuvre thus shadows the assessment of Wimsatt’s own reputation as a foundational icon of criticism, making his universals personally concrete. While at the time of his death in 1975, Wellek could state with confidence that “Wimsatt will be remembered mainly as a theorist of literature,” the headline of his New York Times obituary memorialized him as “Yale expert on 1700’s authors.” The Prose Style of Samuel Johnson (1941), based on Wimsatt’s dissertation, began with a chapter on style and meaning. In his second book, Philosophic Words: A Study of Style and Meaning in the Rambler and Dictionary of Samuel Johnson (1948), Wimsatt described his endeavor, one worthy of a literary-critical James Boswell, as a “history of Johnson’s mind” rooted in the unique properties of Johnson’s scientific language, words that do the metaphorical work of connecting body to mind and the world to the text. While Johnson served as Wimsatt’s exemplary test case for stylistic analysis, Pope, in all his embodied uniqueness, informed Wimsatt’s attempts to conceive of style in the abstract. Style for Wimsatt was always inseparable from meaning, just as, and perhaps because, the author was never fully absent from the text. That Pope should get two essays to himself in The Verbal Icon and is the only author to make top billing in an essay title in that volume drives this point home. That Wimsatt named his own son Alexander makes it personal.

Wimsatt’s lifelong preoccupation with Pope and the successfully realized intentions of eighteenth-century authors reminds us that he practiced theory as part of a group of scholars who studied the poet whose spine, so his contemporaries speculated, was bent by excessive devotion to literature. For Wimsatt and his fellow scholar-collectors at Yale, Pope embodied the ways in which art is inseparable from the material world it represents. Yet by 1975 Wimsatt himself, with all his eccentricities and eighteenth-century preoccupations, his “towering figure” of nearly seven feet sublimated into disembodied monumental status, had taken his place in Yale’s history, a history at the heart of our profession, by disappearing into the theoretical ether. We can see an alternative trajectory in the evolution of cover choices for Wimsatt’s Rinehart edition of the poetry and prose of Alexander Pope, part of a series used in many undergraduate classrooms. Wimsatt noted in a talk given to Yale undergraduates in 1959 that his obsession with Pope’s iconography began with his search for a proper cover image. First published with a plain generic cover in 1951, the 1972 edition published shortly before Wimsatt’s death shows William Hoare’s red crayon drawing, a rare full-length image of Pope, an “original taken without his knowledge,” curved spine and all (fig. 2). When we view the verbal icon through the lens of Wimsatt’s fascination with Pope, its author seems to kick it, like Johnson famously did the stone in response to Bishop Berkeley’s assertion of the nonexistence of matter, to refute it thus. The timeless abstraction of Wimsatt’s theory, in other words, is haunted by the distinctively embodied and loquacious ghost of the poet who complained in Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot that “ev’ry Coxcomb knows me by my Style.” If personification, as Marc Redfield has suggested, is the key to understanding theory at Yale—Harold Bloom standing for aesthetics, Paul de Man standing for theory—what does Wimsatt, behind the busts of Pope, stand for? Perhaps he is standing for style. Resisting autobiography as Romantic de-facement, he pursues the multiple versions of the face of the particular author in which the animate and inanimate forces of language unite, grounding his militant objectivity in embodied particularity in the style of Pope. Continue reading …

HELEN DEUTSCH is Professor of English and Director of the Center for 17th- & 18th-Century Studies and William Andrews Clark Memorial Library at UCLA. She has been writing about Alexander Pope for the entirety of her adult life and is now at work on a book on Jonathan Swift and Edward Said.

HELEN DEUTSCH is Professor of English and Director of the Center for 17th- & 18th-Century Studies and William Andrews Clark Memorial Library at UCLA. She has been writing about Alexander Pope for the entirety of her adult life and is now at work on a book on Jonathan Swift and Edward Said.

In 1831 Virginia, Nat Turner led a slave rebellion that killed fifty-five whites; after more than two months in hiding, he was captured, convicted, and executed. The figure of Turner had an immediate and broad impact on the American South, and his rebellion remains one of the most momentous episodes in American history.

In 1831 Virginia, Nat Turner led a slave rebellion that killed fifty-five whites; after more than two months in hiding, he was captured, convicted, and executed. The figure of Turner had an immediate and broad impact on the American South, and his rebellion remains one of the most momentous episodes in American history.

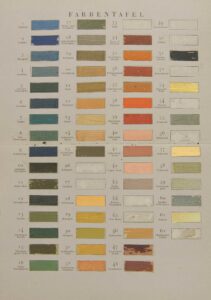

The clue to the pattern of numbers cross-referencing the fields in individual paintings with other pictures by Poussin is offered by a chart (Farbentafel) in the back of the book, where sixty-two brushstrokes of oil paint were applied to sixty-two printed rectangles. Grautoff made it possible to analyze Poussin’s palette through systematic chromatic separation, numerical hue assignment, and graphic indexing.

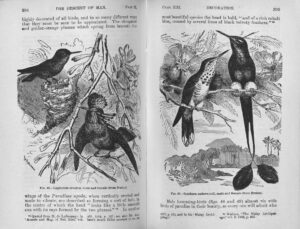

The clue to the pattern of numbers cross-referencing the fields in individual paintings with other pictures by Poussin is offered by a chart (Farbentafel) in the back of the book, where sixty-two brushstrokes of oil paint were applied to sixty-two printed rectangles. Grautoff made it possible to analyze Poussin’s palette through systematic chromatic separation, numerical hue assignment, and graphic indexing. Arguing that aesthetic preference generates the historical forms of human racial and gender difference inThe Descent of Man, Charles Darwin offers an alternative account of aesthetic autonomy to the Kantian or idealist account. Darwin understands the aesthetic sense to be constitutive of scientific knowledge insofar as scientific knowledge entails the natural historian’s fine discrimination of formal differences and their dynamic interrelations within a unified system. Natural selection itself works this way, Darwin argues inThe Origin of Species; in The Descent of Man he makes the case for the natural basis of the aesthetic while relativizing particular aesthetic judgments. Libidinally charged—in Kantian phrase, “interested”—the aesthetic sense nevertheless comes historically adrift from its functional origin in rites of courtship.

Arguing that aesthetic preference generates the historical forms of human racial and gender difference inThe Descent of Man, Charles Darwin offers an alternative account of aesthetic autonomy to the Kantian or idealist account. Darwin understands the aesthetic sense to be constitutive of scientific knowledge insofar as scientific knowledge entails the natural historian’s fine discrimination of formal differences and their dynamic interrelations within a unified system. Natural selection itself works this way, Darwin argues inThe Origin of Species; in The Descent of Man he makes the case for the natural basis of the aesthetic while relativizing particular aesthetic judgments. Libidinally charged—in Kantian phrase, “interested”—the aesthetic sense nevertheless comes historically adrift from its functional origin in rites of courtship.

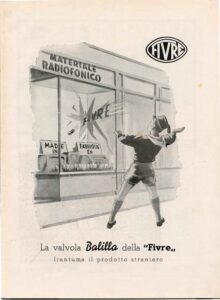

In this study, Danielle Simon investigates a series of experimental television broadcasts undertaken by Italian Fascism’s national broadcasting entity, the Ente Italiano per le Audizioni Radiofoniche, in the years leading up to the Second World War. She explores both the official autarchical policies and the technological limitations that shaped the radio network’s early experiments with television to show that producers’ attitudes regarding medium specificity shaped decisions about programming and musical content. She goes on to suggest that these early sorties into televisual broadcasting left traces that can be seen in the style and political clout of Italian television even today.

In this study, Danielle Simon investigates a series of experimental television broadcasts undertaken by Italian Fascism’s national broadcasting entity, the Ente Italiano per le Audizioni Radiofoniche, in the years leading up to the Second World War. She explores both the official autarchical policies and the technological limitations that shaped the radio network’s early experiments with television to show that producers’ attitudes regarding medium specificity shaped decisions about programming and musical content. She goes on to suggest that these early sorties into televisual broadcasting left traces that can be seen in the style and political clout of Italian television even today.

A short essay by Debarati Sanyal posted on

A short essay by Debarati Sanyal posted on

HELEN DEUTSCH

HELEN DEUTSCH