A translation of Nelly Richard’s essay, “Desajustar el marco del feminismo: una lectura de Judith Butler desde el Sur,” in Representations 158 (Spring 2022): “Proximities: Reading with Judith Butler”

A shorter version of Nelly Richard’s essay was published by Palabra Pública in 2019, along with a translation of that version by Miriam Heard.

Nelly Richard (author) is a critic and essayist. She is the founder and director of the Revista de Crítica Cultural (1990–2008) and the coordinating chair of “Políticas y estéticas de la memoria” at the Museo Reina Sofía Study Center in Madrid (2009–11). She is the author, among other national and international publications, of the following books: Zonas de tumulto: memoria, arte, feminismo (2021), Abismos temporales: Feminismo, estéticas travestis y teoría queer (2018), Crítica y política (2013), Crítica de la memoria (2010), Residuos y metáforas: Ensayos de crítica cultural sobre el Chile de la transición (1998), y Márgenes e Instituciones (1986/2007).

Alex Brostoff (translator) is Assistant Professor of English at Kenyon College. Their research and pedagogy converge at the crossroads of cultural criticism, critical theory, and queer and transfeminist cultural production in twentieth- and twenty-first-century hemispheric American studies. They are the guest editor of a special issue of ASAP/Journal on autotheory, and their scholarship, translations, and public writing have appeared in journals including Critical Times: Interventions in Global Critical Theory, Synthesis: An Anglophone Journal of Comparative Literary Studies, Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies, and Hyperallergic, among others.

Cultural Translation

Following Walter Benjamin, Judith Butler theorizes “cultural translation.” In several of their texts, Butler refers to the ways in which translation underscores how utterances suffer losses; that is, when words move across contexts, they are disfigured in passing from one language to another. But at the same time, words also register a transformative turn, because in language, translation presupposes a movement and renewal of meaning across contexts. This applies to words that travel from language to language in an idiomatic translation. It also applies to theories that change from their original formulation to altered or deviant versions that are revised with respect to intentionality and the contextual conditions and demands of local reception, and that may be marked by failure. In the case of Latin America, asymmetrical symbolic, economic, and cultural power relations between North and South produce colonial encounters surrounded by an aura of legitimacy and superiority in which academic domination exerts a colonizing effect that condemns the periphery to mimesis and repetition. However, what Butler understands as “cultural translation” incorporates contextual difference as a source of critical potential. Pressed up against prescribed meanings, contextual difference accentuates the clash between signs, which thus liberates language from charges of suspicion and defiance. In Butler’s work, “cultural translation” takes up citationality as an active process of reframing and realigning meaning rife with failure and infelicity.

Understood not only as linguistic mediation but as a process of the local resignification of transnational theory, “cultural translation” is subject to associations and dissociations that arise at the intersections of distant and distinct contexts. Butler has claimed that theory “opens up possibilities” that become felicitous only when theory “leaves the context in which it was created in order to enter another context and become something different.”1 They are an authorwhose work and approaches always account for the dissonance of utterances, the asymmetries of contexts, and the slippage in times and modes of cultural reception and reading as creative means of encountering otherness. What happened on Butler’s last trip to Chile relates to their critical openness to the displacement of texts and contexts.2 On the same day that the University of Chile awarded Butler an Honoris Causa something strange happened. It was described in a message sent to Faride Zerán, Vice Chancellor of Communications and Extension at the University of Chile and in charge of organizing Butler’s visit:

Coincidentally, at the time, I was on a bus between Serena and Coquimbo, . . . and I got online to listen to Judith on my phone. A group of boys and girls was also listening to them on speakerphone. Somebody yelled at the driver, “Hey, can you turn off the radio?” and he turned it off. Everyone was listening. . . . And the bus broke into a tremendous applause when Judith was awarded the Honoris Causa. On a bus between Serena and Coquimbo. . . . Beautiful.

There is no logical explanation for the strangeness of this story, especially considering that the scene described occurred on a bus traveling in the north of the country, where academic departments in the rather traditional universities rarely circulate Butler’s work. It is almost inexplicable, then, that young students who were on this bus were so invested in the moment when the University of Chile in Santiago recognized Butler that they asked the driver to turn off his radio so that they could concentrate on the words in the ceremony and applaud the value of this national recognition from such a distance. We can only speculate that the “beauty” of this extraordinarily marginal and remote “cultural translation” of what Butler means was due to more than their written work. What happened here is not the result of academic recognition bestowed by an international award. It is, rather, the affective contagion incited by that name—Judith Butler—that came up more than once in the public debates about gender and feminism that erupted in Chile during the feminist uprising of May 2018, when thousands of students mobilized against patriarchal domination and took to the streets. The spontaneous homage to Butler on the bus traveling between Serena and Coquimbo in northern Chile bridged the gap between the cosmopolitan and the regional due to the feminist political networks that gave Butler’s visit unprecedented national resonance. Beyond academia, such “cultural translation” emerged out-of-place (on a bus traveling in northern Chile) to manifest the reach of those vectors that connect Butler’s name with the desiring bodies of Chilean feminism.

Theory’s Impurities

I like to quote a moment in which Butler writes:

There is a new venue for theory, necessarily impure, where it emerges in and as the very event of cultural translation. This is not the displacement of theory by historicism, nor a simple historicization of theory that exposes the contingent limits of its more generalizable claims. It is, rather, the emergence of theory at the site where cultural horizons meet, where the demand for translation is acute and its promise of success, uncertain.3

To speak of “impure theory” is first and foremost to speak of a theory that does not consider itself self-sufficient but, rather, recognizes that it depends on an array of external factors: various disciplines and communities, times and places, materialities and embodiments, and so forth. To speak of “impure theory” is to evoke a theory that travels through zones of contact and friction that test its limits and conditions. Far from seeking refuge in the methodological purity and infallibility that academicism claims for theory, Butler embraces the ways in which theory’s failures rub up against the partiality of the present. Indeed, the present alters textual content according to the conditions of its critical and political uses and guided by the conflicts and antagonisms imbricated in the social body. Needless to say, this understanding of theory as impurity, which Butler gets from critical theory, has repercussions for the very definitions of “the university.” Their political and intellectual commitment to transforming the future of the humanities presupposes that the inside of the university (including teaching practices, the hierarchies and classification of knowledge, disciplinary organization, and so on) is continually challenged by an outside that is constituted by the ways in which bodies, identities, and genders struggle with the partial meanings of democracy and account for civil society’s heterogeneity.

For Butler, then, theory is formulated as a situated exercise in analysis and understanding that puts thought into dialogue with action, drawing on its strength and energy in the midst of social conflict, and testing out various means of struggle, organization, and participation. Butler has insisted:

Feminist theory is never fully distinct from feminism as a social movement. Feminist theory would have no content were there no movement, and the movement, in its various directions and forms, has always been involved in the act of theory. Theory is an activity that does not remain restricted to the academy. It takes place every time a possibility is imagined, a collective self-reflection takes place, a dispute over values, priorities, and language emerges.4

Outside the academic realm of pure philosophical abstraction, Butler’s theoretical practice serves feminism to: 1) multiply its axes of interpretation with respect to how the dominant sex/gender system of oppression works both symbolically and materially in culture and society; 2) dispute and contest the worldviews that this dominant sex/gender system imposes on hierarchies of knowledge, public structures, and private worlds; 3) instigate new “acts of interpretation” of gender, sexuality, and identity, which produce forms of subjectivity alternative to those prescribed by patriarchal dominance and allied with other forms of sociopolitical resistance.

Along with dismantling and reimagining the coded systems that time and again give the real its discursive shape, it is a theory in action that never renounces exercising judgment as an instance of discernment and responsibility. Critical judgment is the instance that confronts and questions, that takes a stand in debates that agitate the public sphere in the midst of an always troubled and troubling present.

“Gender Ideology” vs. “Critical Theory”

Paradoxically, Butler’s opponents have contributed to their fame by crossing the confined (and often benign) borders of academia, and by publicizing their name as an international symbol of the dangerous moral and sexual dissolution that feminism conjures up today. Indeed, for their enemies, Butler is the author of a Machiavellian “gender ideology” accused of perverting the sexual naturalism of original bodies (irreversibly divided between male and female) and of corrupting the sacred nucleus of the family as a procreative body. But their enemies do not realize that Butler is far more intellectually dangerous than this; they are not the author of “gender ideology” (that is, false consciousness, indoctrination, and manipulation), but quite the contrary. They are a philosopher whose “critical theory” denaturalizes the moral, religious, and cultural foundations of the dominant sexual ideology otherwise known as “patriarchy.” They do not defend “gender ideology,” but, on the contrary, they demonstrate how the heteronormativity that governs the social distribution of bodies is complicit in dominant sexual ideology that never recognizes itself as such. Butler has proven that the true “gender ideology” we should fear is the very one practiced by their opponents: that political and sexual ideology that disguises its dogmatism under the guise of “values,” which are aimed at universalizing and essentializing a religious and metaphysical faith in the feminine-maternal.

As one of the foremost proponents of “critical theory” in contemporary philosophy, Butler puts into textual practice what they do best: a critique of gender ideology (the opposite of what they are said to do) to explain how what the far right calls “sexual nature” is mediated by the construction of signs that invisibly bind bodies, representation, and power in masculinist systems of domination. For the far right, the danger of Butler’s critical and theoretical work is not that the author posits an “ideology of gender,” but that they radically dismantle what social discourse renders invisible as “dominant sexual ideology,” revealing what is hidden in its hierarchies, censorship, and arbitrariness.

Critically Reformulating Gender

Inspired by Butler’s work, queer theory criticizes feminism for its regulatory use of the term gender, in the sense that the term reaffirms the gender binarism of the heterosexual matrix, whose normalizing frame excludes “sexual dissidence” (that is, gay, lesbian, trans, and so on). Queerness’s provocation has been attractive and productive for feminism in introducing a multiplicity of differences into the binary regulation of gender and, in effect, de-essentializing the referent women as the predetermined subject of feminism. Butler’s theories have critically destabilized the discourse on gender normativity and have urged feminism to include marginalized sexualities in its antipatriarchal reformulation of subordinated identities and bodies.

Throughout their work, Butler has insisted that “no simple definition of gender will suffice, and that more important than coming up with a strict and applicable definition is the ability to track the travels of the term through public culture. The term ‘gender’ has become a site of contest for various interests.”5 Butler accounts for the ambivalences and contradictions that disrupt categories, causing endless movements that prompt a constant revision of terms and definitions and that cultivate reversals of meaning that refuse univocal classification. As part of these back-and-forth movements among definitions that are constantly being readjusted, the above citation compels us to ask ourselves the following: in the face of the global rise of the extreme right, which targets feminism as the primary perpetrator of “gender ideology,” isn’t it worth continuing to defend the theoretical approach that the conceptualization of the term gender has represented for feminism? Even if we turn to queer theory to place the subject of feminism under deconstructive suspicion, isn’t it worth continuing to home in on new tactical meanings that can be mobilized against neoconservatism? As Butler notes, today gender has become the main contested signifier around which the interests of the extreme right, neoliberalism, feminism, and the left collide. Although feminism must not ignore the provocations and lessons of queerness, in the face of antifeminist, neoconservative attempts to invalidate the critical potential of gender by renaturalizing bodies and family, this is not an opportune moment to completely abandon the category of gender either. Butler vigilantly urges us to apply ourselves to actively fighting back against all forms of the political deactivation of feminism while simultaneously and self-critically acknowledging that “to question a term, a term like feminism, is to ask how it plays, what investments it bears, what aims it achieves, what alterations it undergoes.”6 This would be the new theoretical and political challenge for feminism at a moment in which the massive advances of feminist organizations on an international scale (for example, the 8M strike in Madrid, the global movement “Ni Una Menos,” May 2018 in Chile, and so on) run up against the far right’s dangerous foreclosures, which seek to disband what has been collectively achieved by feminism in order to authoritatively restore patriarchal power and control.

The Limits of Identitarian Feminism and the Need for Coalition-Building

Their enemies seek to pigeonhole Butler into a niche of queer extravagance in which “queer” is mischaracterized as a dream of endlessly changing gender identity, as if the world were but a stage on which individual spectacles were performed. But Butler knows better than anyone that the real world doesn’t magically turn into a stage where anyone can freely change without restraint. Butler has recognized that the physical, political, economic, and social materiality of bodies subjects them to countless conditions and constraints. Butler theorizes precarious lives and vulnerable bodies, subordinated existences and marginalized communities. They stand out for the intellectual audacity of their political commitment to subjects and groups injured by wars; segregated by the mechanisms of economic exploitation and social oppression; excluded by human rights violations; and so on. They are concerned with those who are subordinated by the targeted and differential violence exerted by the neoliberal system that treats them (poor, migrant, trans people) like waste. Butler’s feminism engages multiple and complex structures of inequality and subordination that do not operate exclusively within the sex/gender system of oppression, always accounting for the social and structural ties between patriarchy and capitalism. For the same reason, Butler leads feminism out of the bastion of identitarian self-referentiality as a separatist group, demonstrating how gender intersects with other identity markers and subject positions (class, race, ethnicity, and so on) that intervene in the configuration of individual and collective subjectivity.

Butler writes:

I don’t think that politics emerge from phrases beginning with “I’m a feminist” or “I’m a queer feminist”. . . given that the coalitions needed to fight against injustice must cut across identity markers. . . . Nor do I believe that strong alliances are a mere collection of identities, or that identities on their own can orient us toward sexual justice, economic equality, antiwar protests, and contemporary struggles against the precariousness and privatization of public education.7

Beginning with the notion that identities are not absolute but relational, transitive, and contingent, Butler has insisted that “to be a feminist” one cannot adhere to the static form of a pure, separatist, and delimited identity of woman, exclusively. Feminist agency allies identities that are not predetermined, identities that aren’t static and fixed but mobile and changing, identities that are socially situated and constructed. Inviting subjects and groups to join the feminist cause so that it gains force as a transformative project requires that it be capable of formulating societal projects that become desirable (rather than threatening or punitive) for those, including men, who are dissatisfied with dominant masculinity and who are likewise engaged in struggles against domination. Butler writes,

The road to defeating a political movement that is based in hatred, without a doubt, cannot reproduce that hatred. We have to continue finding ways of opposing that do not reproduce the violence of those we are faced with. . . . We must find a way of incorporating into our practices the rejection of the normalization and intensification of violence in this world.8

Feminism summons us to develop antiauthoritarian and nonpunitive means of defending points of view about the world, avoiding the annihilating logic of war. It is up to feminism to take charge of the ethical dilemma of knowing how to redirect the aggressive and destructive impulses—born as a response to the social and sexual violence to which women are subjected—toward new alliances between subjectivity, language, and politics that do not reproduce the fatal symptoms of violence.

In response to the abuses perpetrated by the neoliberal machine (as economic indoctrination and as lifestyle) and the brutal order that represses social protest, distinct social behaviors (indignation, rage, frustration, and resentment) tend to subjectively and symptomatically reproduce the effects of the objectifying violence that injures subjects considered disposable by the system of competency and productivity with which neoliberalism governs behavior. However, Butler warns us:

In what sense can such violence be redirected, if it can? . . . Can one work with such formative violence against certain violent outcomes and thus undergo a shift in the iteration of violence? . . . As such, non-violence is a struggle, forming one of the ethical tasks of clinical psychoanalysis and of the psychoanalytic critique of culture.9

According to Butler, feminism stands on the side of this ethical search for nonviolent forms of subjectivity that fight against the inclination to reduce the other to nothing.

Constellating Frames

In their unparalleled book Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (2009), Butler analyzes the function of the “frame,” which consists of exhibiting a scene and giving it visibility (the inside is presented as an image when framed). At the same time, the frame renders visible the invisible set of norms and criteria that is relegated to the outside of the image and that conceals the normative and prescriptive composition that controls representation. Figuratively speaking, one could say that Butler draws on feminism to disrupt, displace, or rupture the frameworks of language and meaning that constitute dominant worldviews (patriarchal, colonial, imperialist, fascist), exploding the play of inside/outside. By making explicit the mechanisms of cultural power and authority that operate from the invisible outside of the frame, which conceals the image and its fictions of truth and transparency, Butler presses on the borders of ideological and sexual systems of representation, mobilizing the margins that surround scenes of seeing to liberate vanishing points and dissidence from the gaze. Rather than allow themself to be “framed” by feminism, Butler moves inside and outside the frames that constrain and crop the fields of established discourses, using feminist theory as a tactical means of positioning and displacing the forces that intervene in each composition.

Just after their visit to Chile, Butler participated in the international conference “Memory at the Crossroads of the Political Present: The Question of Justice,” which took place at the Centro Cultural de la Memoria Haroldo Conti on 8–10 April 2019.10 In front of a massive audience, just after the president of the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo (Asociación Civil Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo) had publicly announced that the 129th granddaughter (who had been kidnapped during the military dictatorship in Argentina) had been identified and rescued, Butler and Estela de Carlotto participated in a solemn closing round table. Visibly moved, Butler chose to suspend the “framework” of feminism, perhaps frustrating the expectations of those who attended the event mainly due to their name as a queer reference. Butler did not speak explicitly about feminism, although they did speak as a feminist by denouncing the criminal alliance between patriarchy and neoliberalism, thus articulating—with absolute gravity and clarity—how a human rights “framework” frames their insistent and persistent demands for truth, justice, and reparation. Butler addressed the urgency of this demand in terms of human rights, taking into consideration the regimes of cruelty and indifference that have befallen Argentina and other countries. They knew how urgent it was to press for the ethical safeguarding of memory of the recent past against the erasures of the past that the neoliberal formation of a time without historicity or morality executes. When Estela de Carlotto (representing Nunca Más11) and Butler (who asserted their North-South solidarity with the Argentine collective Ni Una Menos) embraced, it was the most moving example of how feminism is capable asserting that “the challenge of our time consists of enabling different leftist frameworks to question and alter each other.”12 Butler’s participation in this international conference, alongside Estela de Carlotto, shows how Butler’s interdisciplinary approach (made up of political philosophy, feminist theory, the arts and humanities, as well as social activism) attends to the ways in which constellating, successive frames of reflection, sensitivity, and thought intersect so that the relationship between “affect and judgment” is rendered visible as an “ethical and political judgment and practice.”13

Notes

- Leticia Sabsay, “Interview with Judith Butler,” Página 12, 22 May 2016; my emphasis.

- This visit was organized by the University of Chile for the opening of the academic year (4–5 April 2019) at which Judith Butler was awarded an Honoris Causa. Butler gave the opening talk at the Interdisciplinary Center for the Study of Philosophy, Arts, and Humanities (directed by Pablo Oyarzún) and participated in the public discussion on “Gender, Feminism, and Sexual Dissidence” organized by Nelly Richard.

- Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York ,1999), x; my emphasis.

- Judith Butler, Undoing Gender (New York, 2004), 175–76.

- Ibid., 184; my emphasis.

- Ibid., 180.

- Patricia Soley-Beltrán and Leticia Sabsay, eds., Judith Butler en disputa. Lecturas sobre la performatividad (Barcelona, 2012), 224; my emphasis.

- Enrique Díaz Alvarez, “El poder político del duelo público: entrevista con Judith Butler. El poder político del duelo público,” Revista de la Universidad 846 (May 2019): 40.

- Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (London, 2009), 170.

- The conference was organized by the International Consortium of Critical Theory Programs (University of California, Berkeley), codirected by Judith Butler and Penelope Deutscher. Leonor Arfuch (Argentina) and Nelly Richard (Chile) also participated in the organizing.

- This point was emphasized by the philosopher Luis Ignacio García in discussion at the conference “Memory at the Crossroads of the Political Present: The Question of Justice.”

- Ibid.; my emphasis.

- Butler, Frames of War, 13; my emphasis.

In this essay Martha Feldman proposes that current-day notions of fugitivity, understood in the terms Fred Moten delineates as a category of the irregular that escapes easy representations and predications, can undiscipline music histories in productive ways. Among these: it can inflect musicological thinking through attention to sonic remainders of haunted pasts; it can decenter understandings of the aesthetic; and it can lead to more nuanced thinking about the imbrication of music in an “undercommons” of life that refuses ever to fully sound in harmony, residing instead in a disordered space of restless, noisy sound. Feldman asks, finally, how such thinking, developed by Moten, Nathaniel Mackey, and Daphne Brooks, among others, can remake aspects of musicological thinking about voice.

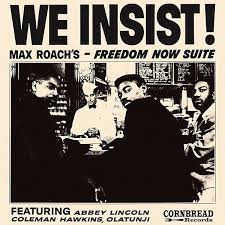

In this essay Martha Feldman proposes that current-day notions of fugitivity, understood in the terms Fred Moten delineates as a category of the irregular that escapes easy representations and predications, can undiscipline music histories in productive ways. Among these: it can inflect musicological thinking through attention to sonic remainders of haunted pasts; it can decenter understandings of the aesthetic; and it can lead to more nuanced thinking about the imbrication of music in an “undercommons” of life that refuses ever to fully sound in harmony, residing instead in a disordered space of restless, noisy sound. Feldman asks, finally, how such thinking, developed by Moten, Nathaniel Mackey, and Daphne Brooks, among others, can remake aspects of musicological thinking about voice. Music here is no more resident solely in physical sound than in sounding music. Wherever found, Black music registers fugitive escape via the phonic eruption, which equates to Black experience and is prefigured by the scream or cry whose originary American instance (to which Moten turns twice, following Saidiya Hartman) are the screams of Frederick Douglass’s Aunt Hester being viciously beaten by her owner. Contained “in the break” (the main title of Moten’s first book), the cry disrupts conventional grammars, strictures, and forms, indexing a breakdown or breakage, but also, relatedly, a breakthrough—a Black event that moves the subject from bondage, conscription, and silence to flight, marronage, and voice. Such flight takes the form of a literal (and for Moten paradigmatic) scream in Abbey Lincoln’s performance of Max Roach and Oscar Brown Jr.’s Freedom Now Suite (1960), a piece that is otherwise “musical” in the ordinary sense. But fugitive flight also takes other sonic forms: a plangent, wailing jazz solo; the explosive shouts in James Brown’s “Cold Sweat”; the lyrical, dancing rhythms of Rakim’s hip-hop, for example—all instances of Moten’s philosophies repeatedly articulating the Black radical aesthetic that Michael Gallope describes “as folds, blurs, oscillations, and rewinds; as displacement and dispossession; as the entanglement of lyricism, performativity, improvisation, and virtuosity.”

Music here is no more resident solely in physical sound than in sounding music. Wherever found, Black music registers fugitive escape via the phonic eruption, which equates to Black experience and is prefigured by the scream or cry whose originary American instance (to which Moten turns twice, following Saidiya Hartman) are the screams of Frederick Douglass’s Aunt Hester being viciously beaten by her owner. Contained “in the break” (the main title of Moten’s first book), the cry disrupts conventional grammars, strictures, and forms, indexing a breakdown or breakage, but also, relatedly, a breakthrough—a Black event that moves the subject from bondage, conscription, and silence to flight, marronage, and voice. Such flight takes the form of a literal (and for Moten paradigmatic) scream in Abbey Lincoln’s performance of Max Roach and Oscar Brown Jr.’s Freedom Now Suite (1960), a piece that is otherwise “musical” in the ordinary sense. But fugitive flight also takes other sonic forms: a plangent, wailing jazz solo; the explosive shouts in James Brown’s “Cold Sweat”; the lyrical, dancing rhythms of Rakim’s hip-hop, for example—all instances of Moten’s philosophies repeatedly articulating the Black radical aesthetic that Michael Gallope describes “as folds, blurs, oscillations, and rewinds; as displacement and dispossession; as the entanglement of lyricism, performativity, improvisation, and virtuosity.”  MARTHA FELDMAN is the Edwin A. and Betty L. Bergman Distinguished Service Professor of Music at the University of Chicago. Her books include Opera and Sovereignty (Chicago, 2007), The Castrato (Oakland, 2015), and the coedited The Voice as Something More: Essays toward Materiality (Chicago, 2019). She is now working on a book on castrato phantoms in twentieth-century Rome.

MARTHA FELDMAN is the Edwin A. and Betty L. Bergman Distinguished Service Professor of Music at the University of Chicago. Her books include Opera and Sovereignty (Chicago, 2007), The Castrato (Oakland, 2015), and the coedited The Voice as Something More: Essays toward Materiality (Chicago, 2019). She is now working on a book on castrato phantoms in twentieth-century Rome.

In reading Henry James’s late novel The Wings of the Dove with Honoré de Balzac’s Seraphita, Amy Hollywood argues that James performs through his novel an act of secular devotion, a memorialization of lost others through which he enables himself to continue to live.

In reading Henry James’s late novel The Wings of the Dove with Honoré de Balzac’s Seraphita, Amy Hollywood argues that James performs through his novel an act of secular devotion, a memorialization of lost others through which he enables himself to continue to live.  In the eighth book of Henry James’s late novel The Wings of the Dove, the young orphaned American heiress Milly Theale has a party. She has rented a Venetian palace from which she is too ill to leave. She is even too sick, although she refuses to acknowledge it, to come down for dinner. But she will, her companion Susan Stringham tells Merton Densher, one of the three key figures in this (doubly) failed marriage plot, come down after dinner, to a candlelit frescoed room filled with music. (“He had found Susan Shepherd alone in the great saloon, where even more candles than their friend’s large common allowance—she grew daily more splendid; they were all struck with it and chaffed her about it—lighted up the pervasive mystery of Style.”)

In the eighth book of Henry James’s late novel The Wings of the Dove, the young orphaned American heiress Milly Theale has a party. She has rented a Venetian palace from which she is too ill to leave. She is even too sick, although she refuses to acknowledge it, to come down for dinner. But she will, her companion Susan Stringham tells Merton Densher, one of the three key figures in this (doubly) failed marriage plot, come down after dinner, to a candlelit frescoed room filled with music. (“He had found Susan Shepherd alone in the great saloon, where even more candles than their friend’s large common allowance—she grew daily more splendid; they were all struck with it and chaffed her about it—lighted up the pervasive mystery of Style.”)

GLQ: A Journal of Gay and Lesbian Studies, founded in 1993, offers an exemplary site for understanding the rise of queer theory, which, from the start, has struggled with the tension between institutionalization and radical resistance. By situating the emergence of this journal and queer theory in general within the AIDS crisis and the literary tradition of the elegy, this essay offers a reading of conventional academic practices as rituals of queer melancholia that comes to challenge the assumption of queer theory’s secularity.

GLQ: A Journal of Gay and Lesbian Studies, founded in 1993, offers an exemplary site for understanding the rise of queer theory, which, from the start, has struggled with the tension between institutionalization and radical resistance. By situating the emergence of this journal and queer theory in general within the AIDS crisis and the literary tradition of the elegy, this essay offers a reading of conventional academic practices as rituals of queer melancholia that comes to challenge the assumption of queer theory’s secularity. KRIS TRUJILLO

KRIS TRUJILLO This article offers a reading of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s 1982 experimental text DICTEE as performing purposefully ambiguous devotional work. As a meditation on unfinished struggles against colonial and patriarchal violence, DICTEE registers devotion’s role in both oppression and liberation. Cha’s engagements with female martyrs, Korean mudang shamanic practice, and colonial languages demonstrate the inseparability of structures of domination and traditions of resistance. The essay argues that even as DICTEE wrestles with inescapable forms of complicity, its efforts to transform perception denaturalize the violence of racial, gendered, and political divisions.

This article offers a reading of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s 1982 experimental text DICTEE as performing purposefully ambiguous devotional work. As a meditation on unfinished struggles against colonial and patriarchal violence, DICTEE registers devotion’s role in both oppression and liberation. Cha’s engagements with female martyrs, Korean mudang shamanic practice, and colonial languages demonstrate the inseparability of structures of domination and traditions of resistance. The essay argues that even as DICTEE wrestles with inescapable forms of complicity, its efforts to transform perception denaturalize the violence of racial, gendered, and political divisions. ELEANOR CRAIG

ELEANOR CRAIG In this article, Robert Davis reads the Proslogion of the medieval theologian Anselm of Canterbury as a drama of seeking and finding God. He guides the reader through a process of rhetorical inventioi, with all of its attendant risks, pleasures, and discontents. The text opens a space or gap of desire, speaking in the voice of the soul who seeks anxiously to find (invenire) God but turns up only absence. The “I” who speaks and addresses itself to itself and to God learns not to close that gap but to inhabit it, affectively and intellectually, just as the monastic rhetor must, when he directs his inventive activity to God.

In this article, Robert Davis reads the Proslogion of the medieval theologian Anselm of Canterbury as a drama of seeking and finding God. He guides the reader through a process of rhetorical inventioi, with all of its attendant risks, pleasures, and discontents. The text opens a space or gap of desire, speaking in the voice of the soul who seeks anxiously to find (invenire) God but turns up only absence. The “I” who speaks and addresses itself to itself and to God learns not to close that gap but to inhabit it, affectively and intellectually, just as the monastic rhetor must, when he directs his inventive activity to God. ROBERT GLENN DAVIS

ROBERT GLENN DAVIS This essay considers an instance of medieval fictionality through the devotional text The Life of the Servant by the Dominican Henry Suso, specifically, through an examination of the “Servant’s” attempt to identify with Christ. Two forms of doubleness issue from this attempt, namely, the human servant seeking to embody the divine without remainder and his figuration as sinner and savior. Insofar as the text allows for a play between these polarities, the servant’s devotional practice can be understood as inhabiting the “as if,” or a kind of fictionality. The temptations of a devotional literalism—fiction striving to overcome its fictionality—is portrayed in the Life alongside a vision of devotion that retains the suspensions and play of the fictional.

This essay considers an instance of medieval fictionality through the devotional text The Life of the Servant by the Dominican Henry Suso, specifically, through an examination of the “Servant’s” attempt to identify with Christ. Two forms of doubleness issue from this attempt, namely, the human servant seeking to embody the divine without remainder and his figuration as sinner and savior. Insofar as the text allows for a play between these polarities, the servant’s devotional practice can be understood as inhabiting the “as if,” or a kind of fictionality. The temptations of a devotional literalism—fiction striving to overcome its fictionality—is portrayed in the Life alongside a vision of devotion that retains the suspensions and play of the fictional. RACHEL SMITH

RACHEL SMITH Like many exegetes before him, the twelfth-century Cistercian abbot Bernard of Clairvaux regarded the lovers in the Song of Songs as allegorical fictions. Yet these prosopopoeial figures remained of profound commentarial interest to him. Bernard’s Sermons on the Song of Songs returns again and again to the literal level of meaning, where text becomes voice and voice becomes fleshly persona. This essay argues that Bernard pursued a distinctive poetics of fictional persons modeled on the dramatic exegesis of Origen of Alexandria as well as on the Song itself. Ultimately, the essay suggests, Bernard’sSermons form an overlooked episode in the literary history of fiction.

Like many exegetes before him, the twelfth-century Cistercian abbot Bernard of Clairvaux regarded the lovers in the Song of Songs as allegorical fictions. Yet these prosopopoeial figures remained of profound commentarial interest to him. Bernard’s Sermons on the Song of Songs returns again and again to the literal level of meaning, where text becomes voice and voice becomes fleshly persona. This essay argues that Bernard pursued a distinctive poetics of fictional persons modeled on the dramatic exegesis of Origen of Alexandria as well as on the Song itself. Ultimately, the essay suggests, Bernard’sSermons form an overlooked episode in the literary history of fiction. JULIE ORLEMANSKI

JULIE ORLEMANSKI