by Cannon Schmitt

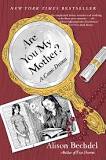

The essay opens with a page spread from Alison Bechdel’s 2012 graphic memoir, Are You My Mother? Cannon Schmitt then begins:

What do we require of these pages? Or, to anthropomorphize and so shift the emphasis: what do they require of us? Such questions are at once theoretical and methodological, and the potential answers are so varied that reducing them to any binary between x or y way of proceeding would clearly be insufficient. Nonetheless, at present one pair of options stands out among others: should we interpret or should we describe? Is our task as readers, viewers, critics, scholars, and theorists the interpretive one of assigning or discerning meaning, crafting a reading, making the object of our attention speak its hidden truth? Or is it, on the contrary, the descriptive one of limning all the details, redoubling the object in our commentary on it, refusing the obviousness of the obvious by exhaustively accounting for what is to be read or seen?

What do we require of these pages? Or, to anthropomorphize and so shift the emphasis: what do they require of us? Such questions are at once theoretical and methodological, and the potential answers are so varied that reducing them to any binary between x or y way of proceeding would clearly be insufficient. Nonetheless, at present one pair of options stands out among others: should we interpret or should we describe? Is our task as readers, viewers, critics, scholars, and theorists the interpretive one of assigning or discerning meaning, crafting a reading, making the object of our attention speak its hidden truth? Or is it, on the contrary, the descriptive one of limning all the details, redoubling the object in our commentary on it, refusing the obviousness of the obvious by exhaustively accounting for what is to be read or seen?

I write “on the contrary” as though interpretation and description were opposites, somehow mutually exclusive. This is indeed how they figure in much recent debate. To take only one example, useful because especially explicit: in a 2010 article in differences, Ellen Rooney states categorically that “description as a mode of reading doesn’t work at all.” Attacking the “surface reading” advocated by Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus in the introduction to their special issue of Representations “The Way We Read Now,” Rooney claims that such an approach—and, by clear implication, any similar descriptive method—naively “dreams itself free of . . . the conflicts that emerge when description is defined as always already a matter of interpretation.” But it’s superfluous to quote from the body of the article because all we really need to know appears in its title, which exhorts us not, as the state motto of New Hampshire has it, to “Live Free or Die,” but rather to “Live Free or Describe.” For its opponents, description equals death: death of critical responsibility, death of political engagement, death of relevance.

We have to go back the better part of a century to find someone with a comparably virulent antidescriptive stance. In his now-classic 1936 essay “Narrate or Describe?” the Marxist philosopher and literary critic Georg Lukács codified the aesthetic superiority of what he called narrating to describing. Although the distinction sounds properly narratological, as if it could be arrived at with recourse to categories of analysis such as narrative voice or focalization, in Lukács’s idiosyncratic usage it has to do with something more elusive, namely a writer’s stance toward a fictional world. Novelists narrate when they present a world in flux, riven by forces of change—change, moreover, in which the novelist and her or his narrator have a vested interest. Of necessity, then, narration is committed to action (including inner action: epiphany or disillusionment, for example). It also links every detail in a novel to the fate of that novel’s characters. Narration admits of no filler. Description, by contrast, is all filler. Novelists describe when they enumerate the details of a world in which those details do not finally matter. Description treats as mere backdrop or setting that which, in narration, would be freighted with consequentiality. As a result, description amounts to nothing more than a kind of “still life.”

Narrating and describing, as Lukács elaborates them in connection with fiction, are far from perfectly analogous to the critical approaches of interpreting and describing. Nonetheless, the overlap is significant enough to be instructive. To begin with, Lukács associates description as a fictional mode with death, just as present-day detractors (and even some proponents, including Heather Love) do with description as a critical mode. If his condemnatory labeling of the world rendered via description as “still life” isn’t clear enough on this front, we need only consider in addition the assertion that, in the work of Émile Zola—for Lukács the quintessential practitioner of novelistic description—the problems and contradictions that vex a living reality are “simply described . . . as caput mortuum of a social process.” Latin for “dead head,” caput mortuum was originally an alchemical term used to designate, per the OED, “the residuum remaining after the distillation or sublimation of any substance”: in its current, figurative usage, “worthless residue.” Thus, in “Narrate or Describe?” narration and novelistic description admit of the same relation Love has posited between interpretation and critical description: that of “the fat and the living” to “the thin and the dead.”

Animated, living narration; static, dead description: a stark opposition. But even as he wields it in the service of a partisan history of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century literary production (on which more below), Lukács can find no novelist who only narrates or only describes. Despite the either/or choice of its titular question, that is, “Narrate or Describe?” answers with a both/and: narration and description require each other. I call attention to this apparent contradiction not as an example of faulty logic or inconsistent positions but instead as a useful model for how we might understand the related opposition between interpretation and description. The point is not that we cannot distinguish between the two. It is, rather, that they depend on and implicate each other in ways that render jettisoning either untenable. That no critical description can purify itself of interpretation is hardly news: such antidescriptive absolutism is now so widespread in the humanities as to constitute a kind of truism. But the inevitability of interpretation’s reliance on description has found few standard bearers. In what follows I make the case for that reliance by way of Lukács, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006), and, finally, those two pages from Are You My Mother? with which I began. Continue reading …

This essay is a contribution to our special issue “Description Across Disciplines” edited by Sharon Marcus, Heather Love, and Stephen Best. You can read the introduction to that issue here.

CANNON SCHMITT, Professor of English and Associate Director of the PhD program in English at the University of Toronto, is the author of two books, Darwin and the Memory of the Human: Evolution, Savages, and South America (2009; paperback reprint 2013) and Alien Nation: Nineteenth-Century Gothic Fictions and English Nationality (1997), and co-editor of Victorian Investments: New Perspectives on Finance and Culture (2008). His essays have appeared in Representations, Victorian Studies, ELH, Genre, and elsewhere. He is now at work on the sea in Victorian fiction and the possibility of literal reading.

Mediterranean, the French state razed a portion of Calais’s “jungle,” encampments that currently shelter 10,000 refugees, while building a container camp. In this essay, an analysis of recent film and photography highlights practices of resistance to the interplay of humanitarian compassion and securitarian repression, nuancing the view of borderscapes as sites of total biopolitical capture, and of refugees as bare life. Read the full advance version of this essay free of charge here.

Mediterranean, the French state razed a portion of Calais’s “jungle,” encampments that currently shelter 10,000 refugees, while building a container camp. In this essay, an analysis of recent film and photography highlights practices of resistance to the interplay of humanitarian compassion and securitarian repression, nuancing the view of borderscapes as sites of total biopolitical capture, and of refugees as bare life. Read the full advance version of this essay free of charge here.

What do we require of these pages? Or, to anthropomorphize and so shift the emphasis: what do they require of us? Such questions are at once theoretical and methodological, and the potential answers are so varied that reducing them to any binary between x or y way of proceeding would clearly be insufficient. Nonetheless, at present one pair of options stands out among others: should we interpret or should we describe? Is our task as readers, viewers, critics, scholars, and theorists the interpretive one of assigning or discerning meaning, crafting a reading, making the object of our attention speak its hidden truth? Or is it, on the contrary, the descriptive one of limning all the details, redoubling the object in our commentary on it, refusing the obviousness of the obvious by exhaustively accounting for what is to be read or seen?

What do we require of these pages? Or, to anthropomorphize and so shift the emphasis: what do they require of us? Such questions are at once theoretical and methodological, and the potential answers are so varied that reducing them to any binary between x or y way of proceeding would clearly be insufficient. Nonetheless, at present one pair of options stands out among others: should we interpret or should we describe? Is our task as readers, viewers, critics, scholars, and theorists the interpretive one of assigning or discerning meaning, crafting a reading, making the object of our attention speak its hidden truth? Or is it, on the contrary, the descriptive one of limning all the details, redoubling the object in our commentary on it, refusing the obviousness of the obvious by exhaustively accounting for what is to be read or seen? Hidden Hitchcock, D. A. Miller does what seems impossible: he discovers what has remained unseen in Hitchcock’s movies, a secret style that imbues his films with a radical duplicity.

Hidden Hitchcock, D. A. Miller does what seems impossible: he discovers what has remained unseen in Hitchcock’s movies, a secret style that imbues his films with a radical duplicity.

GEORGINA KLEEGE

GEORGINA KLEEGE In what follows, I will look at two writers from the French eighteenth century whose work illustrates the contingency of modern categories and definitions of description. The first is the famous naturalist and renowned stylist Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, whose multivolume Histoire naturelle spurred the vogue for natural history across Europe in the second half of the eighteenth century. The second is the once-celebrated but now obscure poet Jacques Delille, who took the Scottish poet James Thomson as his model and introduced the so-called genre of descriptive poetry in France in the last decades of the Old Regime. Taken together, these two writers exemplify what the great naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier called “the age of description.” This age has fallen out of view since Cuvier’s lifetime, lost to the modern fracture between literature and science. Yet I will argue that it holds special relevance for us today, at a time when short-story writers and political theorists alike share an impulse to ascribe agency to nonhuman things and to question the centrality of human perspectives. One of the biggest surprises to emerge from the unfamiliar landscape of the eighteenth-century age of description is its elaboration of a poetics of description grounded in dramatic shifts in scale and nonhuman perspectives on nature.

In what follows, I will look at two writers from the French eighteenth century whose work illustrates the contingency of modern categories and definitions of description. The first is the famous naturalist and renowned stylist Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, whose multivolume Histoire naturelle spurred the vogue for natural history across Europe in the second half of the eighteenth century. The second is the once-celebrated but now obscure poet Jacques Delille, who took the Scottish poet James Thomson as his model and introduced the so-called genre of descriptive poetry in France in the last decades of the Old Regime. Taken together, these two writers exemplify what the great naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier called “the age of description.” This age has fallen out of view since Cuvier’s lifetime, lost to the modern fracture between literature and science. Yet I will argue that it holds special relevance for us today, at a time when short-story writers and political theorists alike share an impulse to ascribe agency to nonhuman things and to question the centrality of human perspectives. One of the biggest surprises to emerge from the unfamiliar landscape of the eighteenth-century age of description is its elaboration of a poetics of description grounded in dramatic shifts in scale and nonhuman perspectives on nature.