The Ethos and Telos of Michoacán’s Knights Templar

by Claudio Lomnitz

After a brief introduction, the essay begins:

Aporia of the “Cartel”

Since the drug war’s inception in 2006, organized and disorganized violence has claimed approximately 200,000 lives in Mexico, and more than 30,000 people have “disappeared.” In the thirteen years that have transpired since then, more people have been killed in Mexico’s war than in the US invasion of Iraq, and more have been forcibly “disappeared” than during Argentina’s Dirty War. Illegal economies have been revolutionized along the way, in processes that Natalia Mendoza has called “cartelization,” which started with the privatization of trade routes for illegal border traffic, most notably of drugs and migrants, and with the development of a bureaucracy within the illegal economy. Contrary to the general prejudice, “cartels” are not reliant on trade in illegal drugs in any transcendental sense; they rely essentially on the armed privatization of public space, the ransom of public liberties, and the forcible appropriation of public goods.

Since the drug war’s inception in 2006, organized and disorganized violence has claimed approximately 200,000 lives in Mexico, and more than 30,000 people have “disappeared.” In the thirteen years that have transpired since then, more people have been killed in Mexico’s war than in the US invasion of Iraq, and more have been forcibly “disappeared” than during Argentina’s Dirty War. Illegal economies have been revolutionized along the way, in processes that Natalia Mendoza has called “cartelization,” which started with the privatization of trade routes for illegal border traffic, most notably of drugs and migrants, and with the development of a bureaucracy within the illegal economy. Contrary to the general prejudice, “cartels” are not reliant on trade in illegal drugs in any transcendental sense; they rely essentially on the armed privatization of public space, the ransom of public liberties, and the forcible appropriation of public goods.

Because cartelization depends crucially on exacting tribute in exchange for protection, cartels can be seen as the privateers of deregulation, and in Mexico they are involved in the regulation of activities as diverse as drug running, undocumented migration, mining, fishing, logging, commercial agriculture, street vending, prostitution, illegal gasoline traffic, construction, arms trafficking, and appropriation of water sources. They are known as “drug cartels” because the vast wealth that poured in from drug trafficking in the 1990s helped leverage a diversification of activities, most notably in the business of transnational migration, but drugs are not indispensable to cartelization. Protection, territorial control, and the credible fear of unbridled violence are. Indeed, territorial control is an essential requisite for cartelization, but local entrenchment brings with it a core tension, that is, a tension between protection and extortion.

This antinomy between protection and extortion is expressed in social-organizational form as ambivalence between the representation of the cartel as a ruthless business and as a family-like guardian against, or coldly indifferent or downright hostile to, outside forces (such as the government). This tension between bureaucratic and familistic paradigms is inherent in the process of cartelization itself. Indeed, once cartelization sets in, the opposition between the “social bandit” and the regular unmarked brigand gets deeply complicated, because these two modes of criminal self-fashioning must be strategically juggled by the cartel and by individual operators at all times. This is because gaining territorial control requires some degree of redistribution such that a patriarchal rhetoric of protection naturally develops, but the final aim of cartel control is amassing unrestrained translocal organizational power and freely circulating private wealth. As a result, the contradiction between the familistic “man of the people” and the “strictly business” conceits of criminal self-fashioning is an aporia that runs through the whole of the so-called narcoculture. Indeed, the new cultures of criminality that are emerging in Mexico are forged in the space of precisely this contradiction.

The Pledge of the Knights Templar

In what follows, I focus on the Caballeros Templarios (Knights Templar) and, tangentially, on La Familia Michoacana (The Michoacano Family), the organization from which the Templarios stemmed. These two drug cartels are often seen as exceptionally “bizarre and deadly” because they developed what has been characterized as “religious” and “messianic” components. Their exceptionality, however, has a strategic component that reflects and reveals a cultural logic that transcends the Michoacán case.

Michoacán has long been a marihuana producing state, and its Tierra Caliente region has also produced opium poppy since the 1950s. When Colombian cocaine started to be channeled to the United States through Mexican middlemen in the early 1990s, however, the value and scale of Mexico’s drug business surged. The much-galvanized cartels that emerged from this process had their home bases on or near the border, and one, the Tamaulipas-based Gulf Cartel and its “praetorian guard,” Los Zetas, took notice of Michoacán as a valuable asset. This was because Michoacán’s city of Lázaro Cárdenas is Mexico’s largest and most modern port on the Pacific Ocean, and a rail line had been built connecting Lázaro Cardenas to Texas, passing through Mexico’s burgeoning automotive and aerospace manufacturing region in the Bajío. In addition, Michoacán’s Tierra Caliente was home to experienced drug producers and runners, along with a thriving but relatively weak local crime organization known as Los Valencias. Given this tempting combination of factors, the Zetas decided to oust Los Valencias and take control of the state.

In order to do this, they relied on the leadership of a number of Michoacano operators, some of whom later staged a rebellion against the Zetas, forming an organization that differentiated itself by stressing their own local roots and commitments. This was the origin, in 2006, of La Familia Michoacana, whose identitarian strategy for seeking local support against the Zetas lies at the origin of the apparently exceptional familistic and religious bent of both La Familia Michoacana and its splinter group, the Caballeros Templarios, which emerged in 2011. The Templarios’ principal innovation was its code of honor. Thus, whereas La Familia portrayed itself loosely as an organization of Michoacanos pledged to protect the interests of the population of that state, the Caballeros Templarios thought of themselves as sworn members of a quasi-religious order with strict rules of induction for its members.

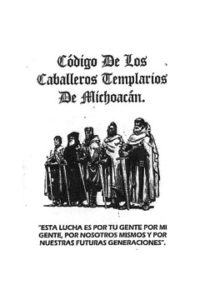

The Code of the Knights Templar of Michoacán (Código de los caballeros templarios de Michoacán) is a twenty-three-page document composed of fifty-three articles, chivalrous illustrations, and the text of the “Templar’s Oath.” It establishes in article 5 that no one who has not been inducted through the proper ritual and sworn to uphold the code may be admitted to the order, and in article 7 it imposes a vow of silence on all its members. Knights Templar must also believe in God (article 9), struggle against materialism (article 10), and fight against injustice and in defense of the values of society (articles 10-14). They must value freedom of expression and freedom of religion (article 15), foment patriotism (article 18), be chivalrous and courteous (articles 19 and 21), be respectful and protective of women (article 22), be sober and good humored (article 30), observe hierarchical discipline (article 31), abstain from killing without approval of the council (article 41), and forfeit their lives and that of their families if they betray the order (article 52).

Despite its punctilious effort at regimentation, and despite its belabored parallels both with the medieval order of the Knights Templar, or perhaps with the Freemason Lodge that existed with that same name in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the cultural significance of this effort of turning an extremely violent crime organization into a chivalrous order is anything but transparent. Indeed, even the code’s practical significance within the organization is murky. In part, this is because the Knights Templar had only a brief flourishing, from approximately 2011 to 2014, which is hardly long enough to consolidate a knightly ethos. The moral code of the Knights Templar was thus more a project than a well-established ritual order.

Moreover, we still know comparatively little about just how much of an effort the Knights Templar actually invested in shaping a unified ritual system. It is true that the writings of Nazario Moreno, who was the guiding intellect of the Knights Templar, were widely distributed amongst members of the organization and that Templar culture and propaganda was on show in the regional capitals of Uruapan, Morelia, and Apatzingán, but we don’t know the degree to which these displays were complemented by a routine drilling of new recruits or whether the distribution of publications was instead oriented to shaping a public image and, as such, was simply a part of the Templario propaganda machine.

To these considerations—insufficient time for institutional consolidation and insufficient information on the operative uses of Nazario Moreno’s key texts—I must add still a third, which is that, like all other drug organizations of this period, the Caballeros Templarios arose and declined in the midst of a war. They expanded rapidly for a time, then contracted and are now dispersed. To consolidate a knightly order under conditions of competitive recruitment and changing allegiances isn’t easy, and it seems likely that the Templars had only limited time and space for the indoctrination of newcomers, especially once the group began to expand into territories beyond Michoacán. Indeed, there is an inherent disconnect between the creation of a knightly order and recruiting an army, which is what the drug war demanded. As a result, the moral code of the Knights Templar was only briefly and unevenly implemented, while the degree to which it was adopted by the organization’s rank and file is still very much in question. Even so, the fleeting phenomenon of this cartel’s moral project provides a useful vantage from which to interrogate the connection between changing mores and Mexico’s narcoculture. Continue reading …

In this essay, anthropologist Claudio Lomnitz mounts an ethnographic exploration of the ethos and mores of Mexico’s contemporary drug culture. He shows that Mexican drug organizations, in their dedication to the business of privatizing public goods, are thus at the same time parallel state structures and trust-based organizations of brothers working to build a collective future. The essay emphasizes the cultural elaboration of competing communitarian and bureaucratic organizational forms and ideals in order to explore the leadership style and moral codes of honor of the Knights Templar, underscoring the centrality of transnational movement in the invention of an acutely gender- and class-based culture of violent domination and caste formation.

CLAUDIO LOMNITZ teaches anthropology at Columbia University and is a regular contributor to the Mexico City press. He is author of Death and the Idea of Mexico (Zone Books, 2005) and The Return of Comrade Ricardo Flores Magón (Zone Books, 2014), among other works. His most recent book is Nuestra América: Utopía y persistencia de una familia judía (Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2018).

CLAUDIO LOMNITZ teaches anthropology at Columbia University and is a regular contributor to the Mexico City press. He is author of Death and the Idea of Mexico (Zone Books, 2005) and The Return of Comrade Ricardo Flores Magón (Zone Books, 2014), among other works. His most recent book is Nuestra América: Utopía y persistencia de una familia judía (Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2018).

Computer screens emerged from the problem of integrating humans, computers, and their environment in a single problem-solving system. More specifically, digital graphics and computerized visualization emerged from the problem of integrating real-time human feedback into computerized radar systems developed by the US military in the early decades of the Cold War.1 In the course of the 1950s and 1960s tinkering engineers adapted techniques developed for visualizing enemy trajectories to somewhat less bellicose applications in computer graphics. Indeed, a wide variety of early computer-generated graphics—from John Whitney’s computer-aided animations and Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad program to early video games like Spacewar! and Tennis for Two—did little more than tweak the techniques of aerial defense into diversions like visualizing abstract patterns and intercepting, so to speak, an opponent’s tennis ball. To borrow film historian Kyle Stine’s felicitous phrasing, by folding picturing and calculation into dual aspects of a single process, these systems joined humans and calculating instruments in a single circuit of information processing. In fire-control systems (as mechanically aided approaches to tracking and targeting the enemy are often called), these feedback circuits often included the environment itself. Together, these elements of the system—human, instrument, environment—formed what I term an ecology of operations that distributed complex mathematical problems in recursive chains.

Computer screens emerged from the problem of integrating humans, computers, and their environment in a single problem-solving system. More specifically, digital graphics and computerized visualization emerged from the problem of integrating real-time human feedback into computerized radar systems developed by the US military in the early decades of the Cold War.1 In the course of the 1950s and 1960s tinkering engineers adapted techniques developed for visualizing enemy trajectories to somewhat less bellicose applications in computer graphics. Indeed, a wide variety of early computer-generated graphics—from John Whitney’s computer-aided animations and Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad program to early video games like Spacewar! and Tennis for Two—did little more than tweak the techniques of aerial defense into diversions like visualizing abstract patterns and intercepting, so to speak, an opponent’s tennis ball. To borrow film historian Kyle Stine’s felicitous phrasing, by folding picturing and calculation into dual aspects of a single process, these systems joined humans and calculating instruments in a single circuit of information processing. In fire-control systems (as mechanically aided approaches to tracking and targeting the enemy are often called), these feedback circuits often included the environment itself. Together, these elements of the system—human, instrument, environment—formed what I term an ecology of operations that distributed complex mathematical problems in recursive chains.

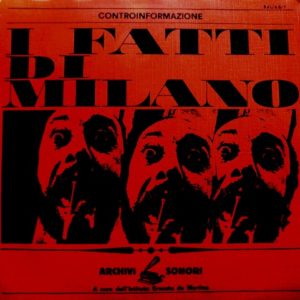

Milan, 19 November 1969, noon. In the heart of the city center, on the streets surrounding the Duomo, two crowds converge. The first, a large group of union workers, is gathered in the Teatro Lirico—there is a general strike all over Italy, the grievance being a rise in the cost of housing. A second group, an assortment of extra-parliamentary left-wing organizations whose Italian crop was in full flourish by 1968, is marching down Via Larga. Since the Teatro Lirico is also on Via Larga, the workers leaving their assembly mingle with the other demonstrators. The crowd swells and heaves. The police intervene. After a few moments, the scene has degenerated: the police, in vans, move toward the demonstrators; the demonstrators find steel tubes in a nearby building site and use them as weapons. A police officer driving one of the vans—Antonio Annarumma—dies in the struggle, in circumstances that remain unclear to this day.

Milan, 19 November 1969, noon. In the heart of the city center, on the streets surrounding the Duomo, two crowds converge. The first, a large group of union workers, is gathered in the Teatro Lirico—there is a general strike all over Italy, the grievance being a rise in the cost of housing. A second group, an assortment of extra-parliamentary left-wing organizations whose Italian crop was in full flourish by 1968, is marching down Via Larga. Since the Teatro Lirico is also on Via Larga, the workers leaving their assembly mingle with the other demonstrators. The crowd swells and heaves. The police intervene. After a few moments, the scene has degenerated: the police, in vans, move toward the demonstrators; the demonstrators find steel tubes in a nearby building site and use them as weapons. A police officer driving one of the vans—Antonio Annarumma—dies in the struggle, in circumstances that remain unclear to this day. DELIA CASADEI

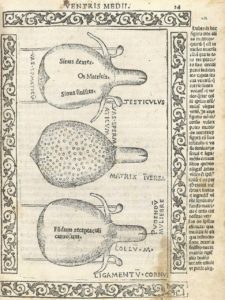

DELIA CASADEI “Not by chance is the possessed body essentially female,” wrote Michel de Certeau in 1975. Few since have disagreed. Up to the close of the last century, studies of early modern demonic possession were dominated by psychoanalytic perspectives, and it seems fair to say that such perspectives are more than usually likely to produce an association between possession and the female body. Scholars such as John Demos, Lyndal Roper, Robin Briggs, and Steven Connor were no crude Freudians and often preferred Melanie Klein’s emphasis on motherhood to de Certeau’s Lacanian prioritization of language. But they were all working within a tradition, derived ultimately from Freud’s predecessor Jean-Martin Charcot, that viewed possession through the lens of hysteria; and despite regular attempts to extend it to male patients, hysteria remains fundamentally associated with femininity. Since both Freud and Charcot were influenced by their own studies of possession, moreover, the apparently natural “fit” between their theories and these phenomena is less convincing than their advocates sometimes assume.

“Not by chance is the possessed body essentially female,” wrote Michel de Certeau in 1975. Few since have disagreed. Up to the close of the last century, studies of early modern demonic possession were dominated by psychoanalytic perspectives, and it seems fair to say that such perspectives are more than usually likely to produce an association between possession and the female body. Scholars such as John Demos, Lyndal Roper, Robin Briggs, and Steven Connor were no crude Freudians and often preferred Melanie Klein’s emphasis on motherhood to de Certeau’s Lacanian prioritization of language. But they were all working within a tradition, derived ultimately from Freud’s predecessor Jean-Martin Charcot, that viewed possession through the lens of hysteria; and despite regular attempts to extend it to male patients, hysteria remains fundamentally associated with femininity. Since both Freud and Charcot were influenced by their own studies of possession, moreover, the apparently natural “fit” between their theories and these phenomena is less convincing than their advocates sometimes assume. BOYD BROGAN is a Centre for Future Health Research Fellow in the Department of History, University of York. He works on sexual abstinence and illness in premodern medicine and on epilepsy, hysteria, and demonic possession from the early modern period to the twentieth century.

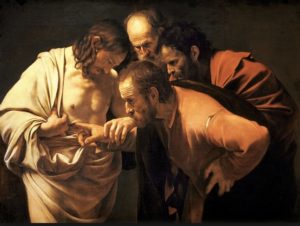

BOYD BROGAN is a Centre for Future Health Research Fellow in the Department of History, University of York. He works on sexual abstinence and illness in premodern medicine and on epilepsy, hysteria, and demonic possession from the early modern period to the twentieth century. Trying to understand pain tolerances as a symptom of culture already gets us entangled in a second distinction: that between pain experiences and pain expressions. Here we enter upon a field of investigation in which the historian of art feels right at home, since questions surrounding the representation of pain in the visual arts have always been part and parcel of imitative art’s charge to represent psychic states and moral virtues—or their opposites—through coded bodily movements, gestures, and physiognomic signs. But questions of pathetic naturalism only get us so far in explaining why, for example, the famous clenched brow of the Trojan priest Laocoön in the eponymous figure group in Rome, as a physiognomic token of pain, communicated to its beholders a “pain-experience” so different from the one conveyed by its counterpart in the Master of Flémalle’s image of a Crucified Thief. We could rehearse the clichéd contrast between heroic death in pagan tragedy and sacrificial suffering in Christian theology to see that distinct narratives of human suffering and conflict are what drive the transferences between pain experiences, pain representations, and pain perceptions. Would we find that it is the very possibility of narrative that makes pain culturally intelligible in the first place? What’s clear is that the full implications of a culture’s narrative-ideological meanings for pain expression in the visual arts would be lost if we failed to attend to the situated functions of images, the peculiar agency they are granted to enlist the beholder’s effort in realizing their effects and completing their meanings in historically specific situations of use. Something of the logic of that agency can be recovered and measured by the forms of response demanded and structured by the image. We may begin, then, with one kind of image that, in portraying the very response it demands, tells us something about the peculiar way spectacular pain expressions registered in late medieval culture.

Trying to understand pain tolerances as a symptom of culture already gets us entangled in a second distinction: that between pain experiences and pain expressions. Here we enter upon a field of investigation in which the historian of art feels right at home, since questions surrounding the representation of pain in the visual arts have always been part and parcel of imitative art’s charge to represent psychic states and moral virtues—or their opposites—through coded bodily movements, gestures, and physiognomic signs. But questions of pathetic naturalism only get us so far in explaining why, for example, the famous clenched brow of the Trojan priest Laocoön in the eponymous figure group in Rome, as a physiognomic token of pain, communicated to its beholders a “pain-experience” so different from the one conveyed by its counterpart in the Master of Flémalle’s image of a Crucified Thief. We could rehearse the clichéd contrast between heroic death in pagan tragedy and sacrificial suffering in Christian theology to see that distinct narratives of human suffering and conflict are what drive the transferences between pain experiences, pain representations, and pain perceptions. Would we find that it is the very possibility of narrative that makes pain culturally intelligible in the first place? What’s clear is that the full implications of a culture’s narrative-ideological meanings for pain expression in the visual arts would be lost if we failed to attend to the situated functions of images, the peculiar agency they are granted to enlist the beholder’s effort in realizing their effects and completing their meanings in historically specific situations of use. Something of the logic of that agency can be recovered and measured by the forms of response demanded and structured by the image. We may begin, then, with one kind of image that, in portraying the very response it demands, tells us something about the peculiar way spectacular pain expressions registered in late medieval culture.

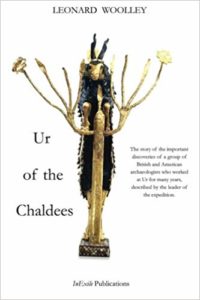

No one could have grasped the relationship between the discovery of civilizations of the remote past, the visualization of their antiquity, and modernity better than Charles Leonard Woolley. One of the most eminent archaeologists of the first half of the twentieth century, Woolley was a doyen of Near-Eastern ancient history, a manipulator of newly developed media, and a celebrity, who noted that “an appeal to the eye is the best way of awakening interest in a new form of knowledge” (that is, archaeology). His observation about the accessibility to mass audiences of a past that had hitherto been largely known only through texts, that had barely existed as a materiality, and that had to be literally dug up to be envisioned, is to be found in his popular manual, Digging Up the Past, which was based on a series of six talks broadcast on the BBC and first published in 1930. By that time Woolley had already written Ur of the Chaldees, which aimed at a popular reading public; had begun publishing the multivolume Excavations at Ur, for professionals; had regularly contributed to the British and North American press; and had toured Britain. As numerous British and American reviewers of the booklet remarked, it proved that archaeology “concerned everyone. Its subject is modern man.”

No one could have grasped the relationship between the discovery of civilizations of the remote past, the visualization of their antiquity, and modernity better than Charles Leonard Woolley. One of the most eminent archaeologists of the first half of the twentieth century, Woolley was a doyen of Near-Eastern ancient history, a manipulator of newly developed media, and a celebrity, who noted that “an appeal to the eye is the best way of awakening interest in a new form of knowledge” (that is, archaeology). His observation about the accessibility to mass audiences of a past that had hitherto been largely known only through texts, that had barely existed as a materiality, and that had to be literally dug up to be envisioned, is to be found in his popular manual, Digging Up the Past, which was based on a series of six talks broadcast on the BBC and first published in 1930. By that time Woolley had already written Ur of the Chaldees, which aimed at a popular reading public; had begun publishing the multivolume Excavations at Ur, for professionals; had regularly contributed to the British and North American press; and had toured Britain. As numerous British and American reviewers of the booklet remarked, it proved that archaeology “concerned everyone. Its subject is modern man.”