The Ambiguity of Devotion: Complicity and Resistance in Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s DICTEE

by Eleanor Craig

This article offers a reading of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s 1982 experimental text DICTEE as performing purposefully ambiguous devotional work. As a meditation on unfinished struggles against colonial and patriarchal violence, DICTEE registers devotion’s role in both oppression and liberation. Cha’s engagements with female martyrs, Korean mudang shamanic practice, and colonial languages demonstrate the inseparability of structures of domination and traditions of resistance. The essay argues that even as DICTEE wrestles with inescapable forms of complicity, its efforts to transform perception denaturalize the violence of racial, gendered, and political divisions.

This article offers a reading of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s 1982 experimental text DICTEE as performing purposefully ambiguous devotional work. As a meditation on unfinished struggles against colonial and patriarchal violence, DICTEE registers devotion’s role in both oppression and liberation. Cha’s engagements with female martyrs, Korean mudang shamanic practice, and colonial languages demonstrate the inseparability of structures of domination and traditions of resistance. The essay argues that even as DICTEE wrestles with inescapable forms of complicity, its efforts to transform perception denaturalize the violence of racial, gendered, and political divisions.

The essay begins:

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha made three visits to Korea between 1978 and 1981, a period of repeated popular uprisings and rapid political change. Cha had not seen Korea since emigrating with her family to Hawai’i and then California when she was twelve, and the passages in DICTEE that seem to refer autobiographically to these return visits register continuities between the time of her departure and the present, as well as ways that both time frames echo past struggles for national independence and democracy. As Elaine Kim notes, this brief period saw dictator Park Chung Hee’s assassination, a 1980 military coup and subsequent uprising contesting military rule, and labor protests. General Chun Doo-hwan declared martial law on May 18, 1980, igniting the Gwangju Uprising, in which soldiers and police killed, assaulted, and tortured a still unknown number of prodemocracy protestors.

In Cha’s multigenre, multimedia book DICTEE, a letter to the narrator’s mother from Seoul, Korea, dated April 19, relates

I am in the same crowd, the same coup, the same revolt, nothing has changed. . . .

. . . They are breaking now, their sounds, not new, you have heard them, so familiar to you now could you ever forget them not in your dreams, the consequences of the sound the breaking. The air is made visible with smoke it grows spreads without control we are hidden inside the whiteness the greyness reduced to parts, reduced to separation. Inside an arm lifts above the head in deliberate gesture and disappears into the thick white from which slowly the legs of another bent at the knee hit the ground the entire body on its left side.

The passage goes on to describe more explicitly the physical impact of tear gas and its overwhelming, disorienting effects: “The stinging, it slices the air it enters thus I lose direction. . . . In tears the air stagnant continues to sting I am crying the sky remnant the gas smoke absorbed the sky I am crying.” This protest scene is a site of violence and death, one that recalls and repeats other such scenes. It is, in fact, difficult to tell when these passages are portraying events contemporary for the narrating voice and when they are blending depictions of these events with more distantly past occurrences. “Step among them the blood that will not erase with the rain on the pavement that was walked upon like the stones where they fell had fallen. Because. Remain dark the stains not wash away.” DICTEE is a meditation on unfinished struggle against entrenched patterns of violence. It is also, I will argue, a study in the practices of devotion that sustain liberatory struggles of all scales (from the individual to the transnational) that simultaneously registers devotion’s role in upholding those same modes of violence.

DICTEE juxtaposes multiple forms of religious, national, familial, and textual devotion. It reiterates these devotional forms in ways that are themselves constitutive, generative modes of practice. Yet it is an uneasy practice, one that raises uncertainties about its own motivations and outcomes. DICTEE’s practices of devotion are neither faithful nor cynical; they offer critical interpretations at the same time that they mobilize ritual power. Rather than striving to determine relative degrees of critique and credulity, irony and sincerity, I want to offer a reading of Cha’s text as engaging in purposefully ambiguous devotional work. DICTEE addresses and inhabits an intertwining web of historical traumas associated with colonialism, gendered and racial oppression, and personal experiences of loss and dislocation. I argue that Cha’s devotional practice, often read as caught between inescapable conditions, attempts to work through sites of apparent impasse by grappling directly with these tensions.

DICTEE is engaged in transformational work that blurs media, traditions, languages, and timescapes in a method that Cha once referred to as “alchemy.” Devotion is a key mode of this work and a significant barrier to undoing systemic violence and historical trauma: it upholds militarism and drives militant anticolonial resistance; it reinforces patriarchy and relativizes masculine power in religious, familial, and political contexts; it confers power and demands sacrifice in cultural mythologies with complex outcomes for women/feminized actors. In these devotional forms and practices, there is no easy division or absolute distinction between complicity and resistance, violence and healing. While DICTEE foregrounds and insists upon these ambiguities, it draws attention to the mechanics of its own artistic work in ways that expose the fractures that propositional statements and linear narratives would allow ideology to conceal. Ultimately, Cha strives to rearrange the patterns of perception that naturalize racial, gendered, and political divisions and (often unconscious) complicity with violent repetitions. Continue reading free of charge for a limited time…

ELEANOR CRAIG is Program Director and Lecturer for the Committee on Ethnicity, Migration, Rights at Harvard University. Craig is co-editor with An Yountae of Beyond Man: Race, Coloniality, and Philosophy of Religion (forthcoming from Duke University Press, 2021) and a member of the inaugural cohort of Emerging Scholars in Political Theology.

ELEANOR CRAIG is Program Director and Lecturer for the Committee on Ethnicity, Migration, Rights at Harvard University. Craig is co-editor with An Yountae of Beyond Man: Race, Coloniality, and Philosophy of Religion (forthcoming from Duke University Press, 2021) and a member of the inaugural cohort of Emerging Scholars in Political Theology.

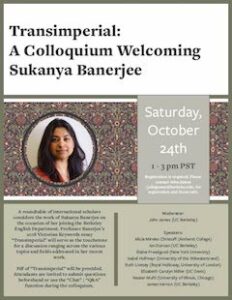

NICOLE T. HUGHES

NICOLE T. HUGHES A roundtable of international scholars considers the work of

A roundtable of international scholars considers the work of  In

In