The Hitchcockian Nudge; or, An Aesthetics of Deception

by Rey Chow and Markos Hadjioannou

The essay begins:

Alfred Hitchcock’s work is, in our view, antithetical to the idea of fallacy, if we understand by fallacy an error committed against a logical mode of validity, an error that needs to be corrected. How this antithesis plays itself out is consistently fascinating. Indeed, it is deception, the state of mind most readily associated with fallacy, that Hitchcock’s cinema loves to portray. In film after film, the condition of being taken in, of mis-taking a situation for what it actually is, constitutes the mise-en-scène not only in the classical, theatrical sense of a setting for the story but also, more critically, in the metaphysical sense of a dynamic play of terrifying forces, the resolution of which (if there is one) often strikes us as conventional, perfunctory, and inadequate. How Hitchcock constructs and furbishes such mise-en-scènes is the focus of the present essay. Specifically, we will examine how he dramatizes deception as a trajectory of the fallacious—that is, as a scenario with its own logics that are played out within the setting of modern Western society.

Alfred Hitchcock’s work is, in our view, antithetical to the idea of fallacy, if we understand by fallacy an error committed against a logical mode of validity, an error that needs to be corrected. How this antithesis plays itself out is consistently fascinating. Indeed, it is deception, the state of mind most readily associated with fallacy, that Hitchcock’s cinema loves to portray. In film after film, the condition of being taken in, of mis-taking a situation for what it actually is, constitutes the mise-en-scène not only in the classical, theatrical sense of a setting for the story but also, more critically, in the metaphysical sense of a dynamic play of terrifying forces, the resolution of which (if there is one) often strikes us as conventional, perfunctory, and inadequate. How Hitchcock constructs and furbishes such mise-en-scènes is the focus of the present essay. Specifically, we will examine how he dramatizes deception as a trajectory of the fallacious—that is, as a scenario with its own logics that are played out within the setting of modern Western society.

To begin with, Hitchcock’s films are full of references to institutions that specialize in the verification of evidence. Populated by police officers, private detectives, lawyers, judges, and medical doctors (in particular psychiatrists), his work demonstrates time and again the investments in law and order as imposed by what Michel Foucault calls disciplinary society, in which private citizens’ behavior—mental and psychological as well as physical—is regulated by an enforcement machinery dedicated to finding them guilty. If law and order rely for their functioning on an implicit notion of human error, so to speak, with crime being the most typical manifestation of such error in a secularized context, it could be argued that fallacy does, in a cynical way, play a big role in Hitchcock. In so far as the professionals specializing in rectifying such error are constantly made fun of, their incompetence a woeful match for the intricate ramifications of the error involved, an institutional attempt to handle fallacy (by way of law, policing, or medicine), Hitchcock suggests, can only lead to the perpetuation of the status quo—what we now call normativization—rather than to the truth. Think of the psychiatrist who proudly offers a scientific explanation for Norman Bates’s personality at the end of Psycho (1960); the judges who absolve Gavin Elster, the mastermind of the crime of his wife’s murder, and the doctor who prescribes Mozart for Scottie in his traumatized state in Vertigo (1958); the police, legal officers, and gynecologist whose findings collectively block the truth of Rebecca’s death from surfacing in Rebecca (1940); or the capitalist Mark Rutland’s self-righteous, pop-psych analysis of his wife Marnie’s kleptomania, frigidity, and strained relationship with her mother in Marnie (1964). Such systemic misses, or disjunctures, abound in Hitchcock’s stories, as if to call attention to the consistent failure of precisely those functionaries who serve as the guardians of modern Western society’s self-validating logic, who stand in, as it were, for its punitive superego.

The heart of Hitchcock’s work, then, lies rather in the gap between modern Western society’s ordinary actors—their habits, desires, beliefs, secrets, and fantasies—on the one hand, and the collective procedures, in various forms of the superego, that are devised to catch and trap them, on the other. That human behavior, especially its errors, is always in excess of these procedures of capture, that there is always a slippage between their actions as such and the so-called objective (or superegoistic) rendering of such actions: this shadowy, messy core of Hitchcock’s cinema is what Pascal Bonitzer means by “Hitchcockian suspense,” which, according to Bonitzer, differs from the more mechanical varieties of suspense commonly found in thrillers. “Hitchcock would appear to have ‘hollowed out’ [the classic thrill of] the cinematic chase that he had inherited from Griffith, much as Mallarmé claimed to have ‘hollowed out’ Baudelaire’s verse,” writes Bonitzer. Instead, the classic “chase” is now staged in the form of a steadily expanding contamination or stain:

Hitchcockian narrative obeys the law that the more a situation is somewhat a priori, familiar or conventional, the more it is liable to become disturbing or uncanny, once one of its constituent elements begins to “turn against the wind.” Scenario and staging consist merely in constructing a natural landscape with its perverse element, and in then charting the outcome. Suspense, by contrast with the accelerated editing of races and chases, depends upon the emphasis which the staging places upon the progressive contamination, the progressive or sudden perversion of the original landscape. . . . The film’s movement invariably proceeds from landscape to stain.

Importantly, Bonitzer points to the distinctive nature of Hitchcock’s configuration of suspense. Suspense in Hitchcock’s universe, that is, does not follow from a narrative of linear acceleration that moves rapidly toward an end to the drama. Instead, Hitchcockian suspense arises from a contamination that progresses steadily in its perverse relationship to the world from within which it grows and to which it belongs. Hitchcock’s films do not so much raise the formulaic question of “whodunit” as confront us with large philosophical questions—of why one commits crimes, of the actual motive and purpose behind a particular crime, and, in particular, of the paradoxical forces of binding that bring into focus unexpected or inexplicable alliances, partnerships, love affairs, symmetries, and couplings (for instance, Uncle Charlie and little Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt [1943], Brandon and Philip in Rope [1948], and Melanie Daniels and the various birds in The Birds [1964]). This is a suspense that suspends normality by letting the latter’s perverse underpinnings unravel alongside it, the way a stain seeps through its surrounding material. As it spreads out, the stain brings to the fore erroneous elements that cannot be simply corrected and irrational elements that cannot be easily explained—in short, fallacies that contaminate concurrently with the very act of logical deduction or construction. Continue reading …

This article considers Alfred Hitchcock’s work in relation to the connotations of “fallacy” within conventional settings of modern Western society. Focusing on two films, Strangers on a Train (1951) and Rear Window (1954), we point to the phenomenon of the incidental push that leads toward an inextricable entanglement of characters, events, and psychic forces in what appear to be logical courses of action. We name this push “the Hitchcockian nudge.”

REY CHOW is Anne Firor Scott Professor of Literature at Duke University. The author of numerous influential monographs, she is also the coeditor, with James A. Steintrager, of the anthology Sound Objects, forthcoming from Duke University Press.

REY CHOW is Anne Firor Scott Professor of Literature at Duke University. The author of numerous influential monographs, she is also the coeditor, with James A. Steintrager, of the anthology Sound Objects, forthcoming from Duke University Press.

MARKOS HADJIOANNOU is Assistant Professor of Literature and of the Arts of the Moving Image at Duke University. He is the author of From Light to Byte: Toward an Ethics of Digital Cinema (2012) and of a number of essays on cinema technologies and aesthetics.

MARKOS HADJIOANNOU is Assistant Professor of Literature and of the Arts of the Moving Image at Duke University. He is the author of From Light to Byte: Toward an Ethics of Digital Cinema (2012) and of a number of essays on cinema technologies and aesthetics.

It is hard not to see that we are living in in an especially fallacious age; fallacies are evidently psychologically compelling. They appeal to our fear, anger, or pity; to our respect for authority; or to our faith in the power of numbers. A president will be blamed for an economic downturn that precedes him or credited for job growth that is inconsequent to his acts. As mistakes of logic, fallacies are not lies and not exactly nonsense either. Fallacies, in other words, are things that, not being valid, “are susceptible of being mistaken” for valid.

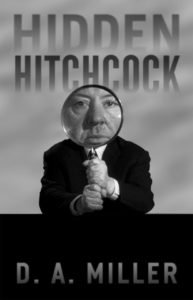

It is hard not to see that we are living in in an especially fallacious age; fallacies are evidently psychologically compelling. They appeal to our fear, anger, or pity; to our respect for authority; or to our faith in the power of numbers. A president will be blamed for an economic downturn that precedes him or credited for job growth that is inconsequent to his acts. As mistakes of logic, fallacies are not lies and not exactly nonsense either. Fallacies, in other words, are things that, not being valid, “are susceptible of being mistaken” for valid. Hidden Hitchcock, D. A. Miller does what seems impossible: he discovers what has remained unseen in Hitchcock’s movies, a secret style that imbues his films with a radical duplicity.

Hidden Hitchcock, D. A. Miller does what seems impossible: he discovers what has remained unseen in Hitchcock’s movies, a secret style that imbues his films with a radical duplicity.