Impersonating Devotion

by Constance M. Furey

What can biblical psalms teach us about literary devotion? An unexpected answer to that question is provided by Philip Sidney’s The Defence of Poesy (1595), a touchstone of literary criticism in its time and in ours. The argument in this essay unfolds from analysis of a single paragraph, which reveals how Sidney’s description of King David’s Psalms challenges our regnant categories in the following way: If today religion connotes fidelity or devotion to an external authority, as for many it does, and if literature entails authorial sovereignty and independent creativity (also a widespread assumption), then Sidney’s approach deviates by equating divine inspiration with poetic creativity. His celebration of variable voices and personae, in particular, undermines the distinction between fidelity and autonomy by offering the psalmist’s voice as a model of transformative self-expression.

What can biblical psalms teach us about literary devotion? An unexpected answer to that question is provided by Philip Sidney’s The Defence of Poesy (1595), a touchstone of literary criticism in its time and in ours. The argument in this essay unfolds from analysis of a single paragraph, which reveals how Sidney’s description of King David’s Psalms challenges our regnant categories in the following way: If today religion connotes fidelity or devotion to an external authority, as for many it does, and if literature entails authorial sovereignty and independent creativity (also a widespread assumption), then Sidney’s approach deviates by equating divine inspiration with poetic creativity. His celebration of variable voices and personae, in particular, undermines the distinction between fidelity and autonomy by offering the psalmist’s voice as a model of transformative self-expression.

The essay begins:

What can biblical psalms teach us about literary devotion? An unexpected answer to that question is provided by Philip Sidney’s The Defence of Poesy (1595), a touchstone of literary criticism in its time and in ours…. Few studies linger over the details of this sketch, for it appears just before Sidney differentiates divine poets from right poets and appeals to Aristotle’s definition of poetry as an art of imitation. This ordering makes it tempting to treat David as prologue to the main event and to conclude—as many commentators have done—that Sidney is most interested in defending secular poetry. Others counter that biblical sources and theological ideas inform all of Sidney’s work. Yet none acknowledge that Sidney’s account of David challenges our regnant categories in the following way: If today religion connotes fidelity or devotion to an external authority, as for many it does, and if literature entails authorial sovereignty and independent creativity (also a widespread assumption), then Sidney’s approach deviates by equating divine inspiration with poetic creativity. His celebration of variable voices and personae, in particular, undermines the distinction between fidelity and autonomy by offering the psalmist’s voice as a model of transformative self-expression.

It is all too easy to take the Psalms for granted and presume that their importance is understood. There is no more important devotional source for biblical traditions, but even those who have never read the Hebrew or Christian Bible, or prayed the Psalms alone or with a religious community, are likely to know and appreciate some of their most familiar phrases and to imagine that the Psalms are also literary because of these memorable expressions of emotion. “Out of the mouths of babes and sucklings hast thou ordained strength,” we read in the King James Bible’s version of Psalm 8. And “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil,” these same translators offer us, in Psalm 23. Many Psalms describe God as “my rock and my fortress” (as in Psalm 31), and the Psalms—from a Hebrew word meaning something sung—soar with words of praise for the creator and creation. The Psalms are, in short, well known as texts that provide comfort to those who grieve, refuge to those in need, and satisfaction for the righteous. But how? What gives the Psalms such a satisfying intensity? Since late antiquity, Christian commentators have emphasized that the power of the Psalms arises not just from their content but also from their form, and from the poetics of voice and personification, in particular. This commentarial tradition’s longstanding interest in poetic personae coalesces in Sidney’s work and should—or so the current essay argues—prompt a new understanding of the relationship between religious and literary devotion.

Certainly most scholars of English Renaissance literature know that their favorite authors read, prayed, and often also created their own poetic psalms. One could fairly say that the Psalms filled the airwaves in premodern Europe. England was no exception. Before Henry VIII dissolved most monasteries, the entire Psalter was recited at least weekly by monks following the Rule of Saint Benedict. The Psalms were less frequently, if no less devoutly, prayed by pious laypeople, who could read them in books of hours and penitential psalm collections and hear and sing them in church. The metrical version of the Book of Psalms by Thomas Sternhold and John Hopkins was the best-selling book in early modern England: appended to the Book of Common Prayer beginning in the 1560s, it was sung and recited by generations of English churchgoers well into the nineteenth century. The Psalms were cited by John Calvin and numerous other reformers as evidence that no other poetry needed to be written. The Bay Psalm Book was the first book printed in British North America, in 1640. And the Psalms unquestionably influenced all early modern lyric poets within Christianity’s orbit.

Yet agreement on the fact that the Psalms matter does not mean consensus on how. The centrality of the question as well as uncertainty about the answer is especially clear when it comes to Sidney. In addition to his memorably vivid appeal to King David in a work avowedly not limited to defending religious poetry, Sidney also embarked on a poetic translation of the entire Psalter. This project was completed by Philip’s sister, Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke, after his untimely death (he was felled by gangrene after being wounded by a Spanish cannonball, when he was only thirty-one years old). The Sidney-Pembroke Psalter is invariably described as metrically inventive, and often praised as inspiring all subsequent English poetry—echoing John Donne’s appreciative insistence that the Sidney translation “both told us what, and taught us how to do.” Accounts of the place of the Psalms in Sidney’s literary theory nevertheless vary widely, ranging from detailed appraisals of his rhetoric and theology to grand claims about how the Psalms provided religious cover for what was ultimately a secular vision of imaginative writing.

What these assessments have in common are two mistaken (and usually unstated) assumptions. First, that when Sidney talks about the poet being “lifted up with the vigour of his own invention,” he must be talking about a singular voice. Second, that this description cannot apply to the divine poet, because his creative strength would come from God rather than “his own invention.” Both impressions can find textual support. Sidney regularly refers to “poet” in the singular, and “own” had the same meaning in his day as in ours, connoting possession by a singular person or thing. And Sidney refers to both “divine poets” and “right poets,” appearing to distinguish between them. Yet these unexamined notions are wrong. Consequentially so.

This misreading of Sidney arises from a limited understanding of how the poetics of personification and textual voices relate to the personhood of writer and reader. Personification should be understood as connoting both anthropomorphism (attributing human characteristics to nonhuman entities) and voice (a correlation still apparent in the description of grammatical voices, for example, “first person”). Understood in this sense, personification was crucial to Sidney’s conception of poetic force and energy. It was essential to the distinction he draws between poetry’s capacity to deceive and distract, which he condemns, and its unrivaled ability to conjure alternative realities and make them appealing, which he commends. In particular, Sidney’s focus on the rhetorical practices (rather than thematics) of personification, rooted in his devotional experiences of the Psalms, differs in decisive and revealing respects from personification understood, as Susan Stewart has described it, as one of lyric poetry’s primary aims and challenges. Sidney’s account of personification differs from that of modern theorists because he is not concerned, as they are, with the challenges of alienation, objectification, agency, and imaginative writing’s capacity to destabilize reality. The intrigue of Sidney’s work comes from his psychologically astute insistence, informed by a long history of Psalm commentators, that poetry is powerful precisely because it offers readers and writers alike the opportunity to identify with multiple voices, unimpeded by the structural logic of narrative or drama—and thereby offers an alternative to contemporary literary theory’s emphasis on agency and objectification. Continue reading …

CONSTANCE M. FUREY is Professor and Chair in the Department of Religious Studies at Indiana University, Bloomington. Recipient of a multiyear Luce Foundation grant for a collaborative project, “Being Human,” she is also the author of two monographs, most recently Poetic Relations: Faith and Intimacy in the English Reformation, published by the University of Chicago Press. Among other projects, she has written multiple essays on the Immanent Frame blog, including “Human” for the Universe of Terms Project, and is at work on a co-authored book about devotion in religion and literature.

CONSTANCE M. FUREY is Professor and Chair in the Department of Religious Studies at Indiana University, Bloomington. Recipient of a multiyear Luce Foundation grant for a collaborative project, “Being Human,” she is also the author of two monographs, most recently Poetic Relations: Faith and Intimacy in the English Reformation, published by the University of Chicago Press. Among other projects, she has written multiple essays on the Immanent Frame blog, including “Human” for the Universe of Terms Project, and is at work on a co-authored book about devotion in religion and literature.

In the introduction to this special issue, three of the co-editors explain that their goal “is to desegregate religious studies and theology from the humanities more broadly by reasserting religion’s significance to the histories of critique, theory, and literature … [and to] pursue connections between devotional practices, literary production, and contemplative or intellectual labor so as to move the intellectual project called Religion and Literature away from an emphasis on thematics and toward an investigation of practices.”

In the introduction to this special issue, three of the co-editors explain that their goal “is to desegregate religious studies and theology from the humanities more broadly by reasserting religion’s significance to the histories of critique, theory, and literature … [and to] pursue connections between devotional practices, literary production, and contemplative or intellectual labor so as to move the intellectual project called Religion and Literature away from an emphasis on thematics and toward an investigation of practices.”  “The goal of this special issue … is to desegregate religious studies and theology from the humanities more broadly by reasserting religion’s significance to the histories of critique, theory, and literature … [and to] pursue connections between devotional practices, literary production, and contemplative or intellectual labor so as to move the intellectual project called Religion and Literature away from an emphasis on thematics and toward an investigation of practices.”

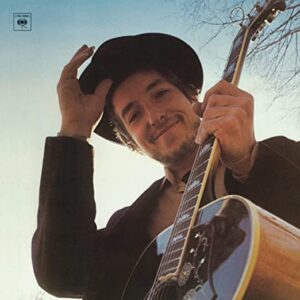

“The goal of this special issue … is to desegregate religious studies and theology from the humanities more broadly by reasserting religion’s significance to the histories of critique, theory, and literature … [and to] pursue connections between devotional practices, literary production, and contemplative or intellectual labor so as to move the intellectual project called Religion and Literature away from an emphasis on thematics and toward an investigation of practices.”  At the close of the 1960s two developments changed the shape of mainstream rock and roll music. The first was a new focus, on the part of a number of influential artists, on music about domestic life—kids, spouses, home. The second was a new interest in blending rock rhythms with instrumentation and themes taken from country music. This essay explores the ways in which these two concerns overlap in the work of Bob Dylan. I argue that Dylan’s work at the turn of the decade offers insights into our own current moment, when the relationship between the public world and the private world is being renegotiated. I show how Dylan’s “country” songs are, in fact, models of self-conscious experimentation that push against the conventions of popular song and highlight the conditions of their own production.

At the close of the 1960s two developments changed the shape of mainstream rock and roll music. The first was a new focus, on the part of a number of influential artists, on music about domestic life—kids, spouses, home. The second was a new interest in blending rock rhythms with instrumentation and themes taken from country music. This essay explores the ways in which these two concerns overlap in the work of Bob Dylan. I argue that Dylan’s work at the turn of the decade offers insights into our own current moment, when the relationship between the public world and the private world is being renegotiated. I show how Dylan’s “country” songs are, in fact, models of self-conscious experimentation that push against the conventions of popular song and highlight the conditions of their own production. Every previous major disaster in human history, from the Black Plague to the Great Depression, has elicited a reimagination of the world, a reinvention of collective life through culture. The COVID-19 pandemic is no exception. The arts and humanities—two areas of inquiry that focus on value and meaning—provide crucial resources for reconceptualizing our lives together during, and after, our current crisis.

Every previous major disaster in human history, from the Black Plague to the Great Depression, has elicited a reimagination of the world, a reinvention of collective life through culture. The COVID-19 pandemic is no exception. The arts and humanities—two areas of inquiry that focus on value and meaning—provide crucial resources for reconceptualizing our lives together during, and after, our current crisis.