by Delia Casadei

The essay begins:

Milan, 19 November 1969, noon. In the heart of the city center, on the streets surrounding the Duomo, two crowds converge. The first, a large group of union workers, is gathered in the Teatro Lirico—there is a general strike all over Italy, the grievance being a rise in the cost of housing. A second group, an assortment of extra-parliamentary left-wing organizations whose Italian crop was in full flourish by 1968, is marching down Via Larga. Since the Teatro Lirico is also on Via Larga, the workers leaving their assembly mingle with the other demonstrators. The crowd swells and heaves. The police intervene. After a few moments, the scene has degenerated: the police, in vans, move toward the demonstrators; the demonstrators find steel tubes in a nearby building site and use them as weapons. A police officer driving one of the vans—Antonio Annarumma—dies in the struggle, in circumstances that remain unclear to this day.

Milan, 19 November 1969, noon. In the heart of the city center, on the streets surrounding the Duomo, two crowds converge. The first, a large group of union workers, is gathered in the Teatro Lirico—there is a general strike all over Italy, the grievance being a rise in the cost of housing. A second group, an assortment of extra-parliamentary left-wing organizations whose Italian crop was in full flourish by 1968, is marching down Via Larga. Since the Teatro Lirico is also on Via Larga, the workers leaving their assembly mingle with the other demonstrators. The crowd swells and heaves. The police intervene. After a few moments, the scene has degenerated: the police, in vans, move toward the demonstrators; the demonstrators find steel tubes in a nearby building site and use them as weapons. A police officer driving one of the vans—Antonio Annarumma—dies in the struggle, in circumstances that remain unclear to this day.

Competing accounts of the event appear almost instantly. Italy’s president, Giuseppe Saragat, releases a public statement laced with imagery of a body politic assailed by lethal pathogens:

This odious crime must serve as a warning to all: to isolate the criminals and put them in a condition of no longer being noxious; their purpose is the destruction of life.

Many demonstrators were illegally incarcerated for several months while they awaited trial. The leading left-wing newspaper, L’Unità, published eyewitness accounts from both striking workers and a judge (Domenico Politanò) at the Milan tribunal, who maintained that “[the police carried out] an aggressive act on a peaceful demonstration.” Other commentators, including left-wing writer Nanni Balestrini, maintained that the police attacked first, that Annarumma collided with another police van, and that his death was subsequently framed as murder in order to antagonize the extra-parliamentary left. The Italian Confederation of Workers’ Unions (CISL) suggested that the extremist left-wing groups were of “suspect provenience,” meaning that they might have been infiltrated, perhaps by neofascists seeking to pin a political murder on the left. Slogans calling to avenge Annarumma’s death appeared on walls across the city. In the police barracks at the Milanese northeastern district of Bicocca, where Annarumma was usually stationed, the climate became increasingly exasperated. Far-right press such as the weekly Il Borghese called for the occupation of the city by the police. When, a few days later, Mario Capanna, leader of the Movimento Studentesco (the university’s leading left-wing group and part of the group accused of Annarumma’s murder), attended the funeral of Annarumma to offer his condolences, he narrowly escaped lynching by a mob of enraged policemen.

The ensuing trial did little to calm this tense atmosphere. While responsibility for Annarumma’s death was officially attributed to the demonstrators, an individual culprit was never found: what the law produced was not the cathartic exhibition of a criminal body, but an immaterial moral shadow cast over a mercurial, disorderly crowd—a collective that could take on different political shades depending on the onlooker. Viewed from the hindsight of the decade that followed, the whole episode—and the atmosphere it generated—was grimly familiar and not unique to Italy. The state of constant urban confrontation, in other words, was one that characterized many nations during the height of the Cold War. This “low-intensity warfare”—the US Army term used to describe the situation in Italy, as well as in Greece, West Germany, and Chile in the 1970s—saw official and unofficial police forces mobilized to curb left-wing political extremism. In Italy, as elsewhere, the decade beginning in 1969 was dubbed the anni di piombo, the years of lead—a period characterized by political violence by way of artillery: bombs detonated on trains and in railway stations and banks and the kidnapping and murder of politicians, activists, and members of the police force.

As I have mentioned, neither the epithet nor the political situation was exclusive to Italy during the years of the Cold War—indeed, the phrase anni di piombo was coined in 1981 by German director Margarethe von Trotta, who made it the title of a film about the tensions between East and West Germany. In Italy, the term referred to a series of urban guerrilla actions resulting from several layers of political conflict: the skyrocketing of private industry profits during the years of the economic miracle (1958–1963) had been accompanied by neglect of the public sector—housing infrastructure, health services, and education—that became the subject of frequent and vociferous protests among workers, university students, and left-wing intellectuals. By the end of the sixties, these sectors had articulated into a myriad of competing extra-parliamentary left-wing groups. Some of these (such as the Movimento Studentesco, the Marxisti Leninisti, and Adriano Sofri’s Lotta Continua) had considerable traction and contacts with Soviet Russia, argued for the necessity of political violence, and had ties with the Communist Red Brigades. Although in conflict with one another over the minutiae of their political programs, all groups protested the parliamentary left, which in 1969 consisted of a first-time coalition of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) and the Christian Democrats (DC). This same government—and anything to the left of it—was also under attack by numerous neofascist groups such as Ordine Nuovo, and Avanguardia Nazionale. Although the plan came to nothing, Julio Valerio Borghese, a naval commander during the fascist regime who continued lobbying for extreme right politics after the war, allegedly gathered armed forces to attempt a coup d’état—now known as the Golpe Borghese—between 7 and 8 December 1970. The US government—which had kept very close ties with the center-left Christian Democrat government since the 1950s—naturally did not want the extreme left to gain traction in Italy; but by the seventies, as some Wikileaks cables have since shown, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was actively invested in discouraging inquiries into the links between neofascist sympathizers and the police, a disquieting position considering that Italy was in the aftermath of an attempted—if badly executed—military coup, and that Kissinger would in 1973 openly support the Chilean golpe against Salvador Allende.

The product of these tensions was an atmosphere in which violent extremes mingled and even were played against one another by a government intent on preserving its precarious stability at all costs. Extreme left-wing groups were often infiltrated by spies from the extreme right, and vice versa. The strategy of “false flagging”—that is, of committing a crime in such a way as to pin responsibility on a particular political group—was a key mode of operation in the late sixties, one whose effect was not so much a successful laying of blame as a deeper destabilization of any identity behind political action. If a crime could be committed so as to look like the work of a leftist group, then the very ideal of activism—that of making direct, immediate dents in a political order—was shattered into a forest of signs, which were then subjected to the vagaries of representation and interpretation.

A period such as the anni di piombo presents a peculiar kind of problem to any historian (let alone a sound historian, as we will see). Unresolved crimes, violence without a culprit, were more rule than exception in this period—it was a time of “terror as usual,” to use Michael Taussig’s sinister oxymoron. Such crimes are always already embedded in a highly sensationalist public record dating back to the violent event itself and woven in a literary and visual corpus that spans, by now, decades. A violent event existed in a particular “climate of representation”—to use Lisa Gitelman’s phrase—through which the event was codified into reports that rooted themselves in the memory of the city’s inhabitants. The climate, in the case of 1970s Italy, was characterized by sensationalist public statements, such as Saragat’s intimation of biopolitical terror, which pointedly fails to identify any political purpose behind the violence other than the “destruction of life.” The sensationalism, though, was not a general matter of rhetoric, of overstatement, or even of metaphorical language. The historian can’t pretend to scrape it off as mere ideology, exposing the live historical flesh underneath. And this is why: in the history of Italian politics that begins with the explosion in Piazza Fontana and extends to the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro, it was hardly ever the loss of life, the most concrete consequence of political violence, that was sensationalized; rather, it was precisely the unintelligibility, the impossibility of conclusive evidence regarding its perpetrators that was staged, proclaimed, bemoaned, and ultimately sold.

This climate of representation, in which unintelligibility is presented as a kind of standalone reality effect (that is, such a picture, or such a witness, is telling the truth because its contents or testimony are unclear), puts the historian in a peculiar double bind. We don’t know, for example, if Annarumma was intentionally murdered or died by accident, perhaps as a result of attempted self-defense. Nonetheless, reporting this particular or any event as a problem, as an unresolved issue, is to appropriate the mode of presentation of the event itself at the time of occurrence, making the historian complicit with the sensationalist press coverage. And yet it is also essentially impossible for the historian to resolve the mystery (and this is, of course, the mode of Italian microhistorians like Carlo Ginzburg, who directly engaged with the historiographical and political problem of the anni di piombo) and demystify the sensationalism: for all the putative resolutions of the Annarumma, Piazza Fontana, and Aldo Moro cases, none of them have yet amounted to an official legal resolution. Indeed, not only is the overblown mode of representation difficult to deflate into a legal resolution, but one could also argue that sensationalism in 1970s Italy aided, rather than defied, the exercise of the law: in response to the Moro murder, Prime Minister Francesco Cossiga passed a law (formulated on 15 December 1979 and passed on 8 February 1980) sanctioning mass incarcerations, unwarranted searches, and more severe punishment for terrorist activities, effectively turning the problem of unintelligibility into permission to persecute, rather than legally try, members of activist groups deemed suspicious.

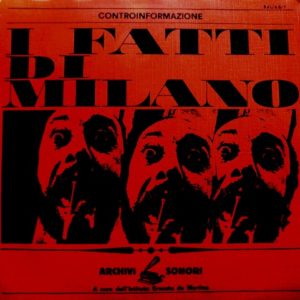

This is not to say that the question of the aesthetic value, the performativity and complex sensationalism of the coverage of political violence at this point in Italian history hasn’t been examined by historians. It is, however, striking that, by and large, these analyses have focused on visual evidence, on either printed media or photography. Verbal media—newspaper articles, interviews, and so on—could also embody terror insofar as they were shown merely to report on what seemed unsettling documentary evidence. Of course visual evidence and its presentation were even more crucial to the building of such an atmosphere—from the typesetting of headlines, to the pictures included with the report, to the street-level “eyewitnesses” on which journalistic reports of this kind so heavily rely. Historians have since produced accounts of precisely the representational work performed by 1970s media, accounts that are largely based on an analysis of images and news clippings. In the case of Italy, a collective study was published in 2011 of an iconic image of Milan’s anni di piombo (a balaclava-wearing demonstrator pointing a gun at armed police), showing the work of representation evident in the technical features as well as press coverage of the photo. There is, on the other hand, a pronounced dearth of critical studies about sound media in these same circumstances. This is an odd lacuna. After all, this is a historical period in which recording technology allows for extensive sonic documentation—not to mention surveillance—of events that could then be broadcast or even circulated as recordings. Is this lack of a critical history of political sound recordings simply a sign that recorded sound has lost the race against visual media as a source of proof, and thus as the subject of historical critique? Or is it that the act of recording sound is considered by default less mediated (more presence than representation) than visual reproduction, and thus, again, less worthy of critical attention? And if so, how might we begin to think of a representational climate for sound in these decades? Continue reading …

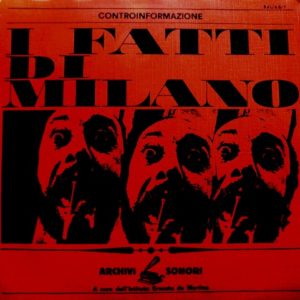

In this essay, musicologist Delia Casadei homes in on the contradiction between the declared purpose of the LP I fatti di Milano and the sound recording it mobilizes toward that end. Drawing on both sound studies and Italian political philosophy, she argues that the record embodies and actively stages idiosyncratic but highly contemporary relationships between music and soundscape, between sound event and its technological reproduction, and ultimately between political event and the act of writing history.

DELIA CASADEI is an Assistant Professor at UC Berkeley. She researches the relation between voice, sound reproduction, and ideologies of language, with special attention to the twentieth century, Italy, and matters of nationhood and race.

DELIA CASADEI is an Assistant Professor at UC Berkeley. She researches the relation between voice, sound reproduction, and ideologies of language, with special attention to the twentieth century, Italy, and matters of nationhood and race.

Three distinguished UC Berkeley scholars—

Three distinguished UC Berkeley scholars—

It passes for an unassailable truth that the slave past provides an explanatory prism for understanding the black political present. In None Like Us Stephen Best reappraises what he calls “melancholy historicism”—a kind of crime scene investigation in which the forensic imagination is directed toward the recovery of a “we” at the point of “our” violent origin. Best argues that there is and can be no “we” following from such a time and place, that black identity is constituted in and through negation, taking inspiration from David Walker’s prayer that “none like us may ever live again until time shall be no more.” Best draws out the connections between a sense of impossible black sociality and strains of negativity that have operated under the sign of queer. In None Like Us the art of El Anatsui and Mark Bradford, the literature of Toni Morrison and Gwendolyn Brooks, even rumors in the archive, evidence an apocalyptic aesthetics, or self-eclipse, which opens the circuits between past and present and thus charts a queer future for black study.

It passes for an unassailable truth that the slave past provides an explanatory prism for understanding the black political present. In None Like Us Stephen Best reappraises what he calls “melancholy historicism”—a kind of crime scene investigation in which the forensic imagination is directed toward the recovery of a “we” at the point of “our” violent origin. Best argues that there is and can be no “we” following from such a time and place, that black identity is constituted in and through negation, taking inspiration from David Walker’s prayer that “none like us may ever live again until time shall be no more.” Best draws out the connections between a sense of impossible black sociality and strains of negativity that have operated under the sign of queer. In None Like Us the art of El Anatsui and Mark Bradford, the literature of Toni Morrison and Gwendolyn Brooks, even rumors in the archive, evidence an apocalyptic aesthetics, or self-eclipse, which opens the circuits between past and present and thus charts a queer future for black study.

Computer screens emerged from the problem of integrating humans, computers, and their environment in a single problem-solving system. More specifically, digital graphics and computerized visualization emerged from the problem of integrating real-time human feedback into computerized radar systems developed by the US military in the early decades of the Cold War.1 In the course of the 1950s and 1960s tinkering engineers adapted techniques developed for visualizing enemy trajectories to somewhat less bellicose applications in computer graphics. Indeed, a wide variety of early computer-generated graphics—from John Whitney’s computer-aided animations and Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad program to early video games like Spacewar! and Tennis for Two—did little more than tweak the techniques of aerial defense into diversions like visualizing abstract patterns and intercepting, so to speak, an opponent’s tennis ball. To borrow film historian Kyle Stine’s felicitous phrasing, by folding picturing and calculation into dual aspects of a single process, these systems joined humans and calculating instruments in a single circuit of information processing. In fire-control systems (as mechanically aided approaches to tracking and targeting the enemy are often called), these feedback circuits often included the environment itself. Together, these elements of the system—human, instrument, environment—formed what I term an ecology of operations that distributed complex mathematical problems in recursive chains.

Computer screens emerged from the problem of integrating humans, computers, and their environment in a single problem-solving system. More specifically, digital graphics and computerized visualization emerged from the problem of integrating real-time human feedback into computerized radar systems developed by the US military in the early decades of the Cold War.1 In the course of the 1950s and 1960s tinkering engineers adapted techniques developed for visualizing enemy trajectories to somewhat less bellicose applications in computer graphics. Indeed, a wide variety of early computer-generated graphics—from John Whitney’s computer-aided animations and Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad program to early video games like Spacewar! and Tennis for Two—did little more than tweak the techniques of aerial defense into diversions like visualizing abstract patterns and intercepting, so to speak, an opponent’s tennis ball. To borrow film historian Kyle Stine’s felicitous phrasing, by folding picturing and calculation into dual aspects of a single process, these systems joined humans and calculating instruments in a single circuit of information processing. In fire-control systems (as mechanically aided approaches to tracking and targeting the enemy are often called), these feedback circuits often included the environment itself. Together, these elements of the system—human, instrument, environment—formed what I term an ecology of operations that distributed complex mathematical problems in recursive chains.

Michael Lucey

Michael Lucey Milan, 19 November 1969, noon. In the heart of the city center, on the streets surrounding the Duomo, two crowds converge. The first, a large group of union workers, is gathered in the Teatro Lirico—there is a general strike all over Italy, the grievance being a rise in the cost of housing. A second group, an assortment of extra-parliamentary left-wing organizations whose Italian crop was in full flourish by 1968, is marching down Via Larga. Since the Teatro Lirico is also on Via Larga, the workers leaving their assembly mingle with the other demonstrators. The crowd swells and heaves. The police intervene. After a few moments, the scene has degenerated: the police, in vans, move toward the demonstrators; the demonstrators find steel tubes in a nearby building site and use them as weapons. A police officer driving one of the vans—Antonio Annarumma—dies in the struggle, in circumstances that remain unclear to this day.

Milan, 19 November 1969, noon. In the heart of the city center, on the streets surrounding the Duomo, two crowds converge. The first, a large group of union workers, is gathered in the Teatro Lirico—there is a general strike all over Italy, the grievance being a rise in the cost of housing. A second group, an assortment of extra-parliamentary left-wing organizations whose Italian crop was in full flourish by 1968, is marching down Via Larga. Since the Teatro Lirico is also on Via Larga, the workers leaving their assembly mingle with the other demonstrators. The crowd swells and heaves. The police intervene. After a few moments, the scene has degenerated: the police, in vans, move toward the demonstrators; the demonstrators find steel tubes in a nearby building site and use them as weapons. A police officer driving one of the vans—Antonio Annarumma—dies in the struggle, in circumstances that remain unclear to this day. DELIA CASADEI

DELIA CASADEI In this a bold new account of how celebrity works, Marcus draws on scrapbooks, personal diaries, and vintage fan mail to trace celebrity culture back to its nineteenth-century roots, when people the world over found themselves captivated by celebrity chefs, bad-boy poets, and actors such as the “divine” Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923), as famous in her day as the Beatles in theirs.

In this a bold new account of how celebrity works, Marcus draws on scrapbooks, personal diaries, and vintage fan mail to trace celebrity culture back to its nineteenth-century roots, when people the world over found themselves captivated by celebrity chefs, bad-boy poets, and actors such as the “divine” Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923), as famous in her day as the Beatles in theirs.

“Not by chance is the possessed body essentially female,” wrote Michel de Certeau in 1975. Few since have disagreed. Up to the close of the last century, studies of early modern demonic possession were dominated by psychoanalytic perspectives, and it seems fair to say that such perspectives are more than usually likely to produce an association between possession and the female body. Scholars such as John Demos, Lyndal Roper, Robin Briggs, and Steven Connor were no crude Freudians and often preferred Melanie Klein’s emphasis on motherhood to de Certeau’s Lacanian prioritization of language. But they were all working within a tradition, derived ultimately from Freud’s predecessor Jean-Martin Charcot, that viewed possession through the lens of hysteria; and despite regular attempts to extend it to male patients, hysteria remains fundamentally associated with femininity. Since both Freud and Charcot were influenced by their own studies of possession, moreover, the apparently natural “fit” between their theories and these phenomena is less convincing than their advocates sometimes assume.

“Not by chance is the possessed body essentially female,” wrote Michel de Certeau in 1975. Few since have disagreed. Up to the close of the last century, studies of early modern demonic possession were dominated by psychoanalytic perspectives, and it seems fair to say that such perspectives are more than usually likely to produce an association between possession and the female body. Scholars such as John Demos, Lyndal Roper, Robin Briggs, and Steven Connor were no crude Freudians and often preferred Melanie Klein’s emphasis on motherhood to de Certeau’s Lacanian prioritization of language. But they were all working within a tradition, derived ultimately from Freud’s predecessor Jean-Martin Charcot, that viewed possession through the lens of hysteria; and despite regular attempts to extend it to male patients, hysteria remains fundamentally associated with femininity. Since both Freud and Charcot were influenced by their own studies of possession, moreover, the apparently natural “fit” between their theories and these phenomena is less convincing than their advocates sometimes assume. BOYD BROGAN is a Centre for Future Health Research Fellow in the Department of History, University of York. He works on sexual abstinence and illness in premodern medicine and on epilepsy, hysteria, and demonic possession from the early modern period to the twentieth century.

BOYD BROGAN is a Centre for Future Health Research Fellow in the Department of History, University of York. He works on sexual abstinence and illness in premodern medicine and on epilepsy, hysteria, and demonic possession from the early modern period to the twentieth century.