Prosaic Suffering: Bourgeois Tragedy and the Aesthetics of the Ordinary

by Alex Eric Hernandez

The essay begins:

In 1778, Samuel Johnson was asked to weigh in on the prose of a new bourgeois tragedy, The Female Gamester. Its author, Gorges Edmond Howard, was a Dublin-based lawyer and literary dabbler whose attempt at domestic drama might have been wholly forgotten were it not for the fragment of Johnsoniana he preserved in its preface. Having originally written the play in a mixture of prose and verse, Howard had been advised by “several of [his] literary acquaintance” that his “not much exalted” prose was much more suitable to the “scene . . . laid in private life, and chiefly among those of middling rank.” For many, it seems, the bourgeoisie suffered in prose. But Johnson, Howard recalls, would have none of this:

In 1778, Samuel Johnson was asked to weigh in on the prose of a new bourgeois tragedy, The Female Gamester. Its author, Gorges Edmond Howard, was a Dublin-based lawyer and literary dabbler whose attempt at domestic drama might have been wholly forgotten were it not for the fragment of Johnsoniana he preserved in its preface. Having originally written the play in a mixture of prose and verse, Howard had been advised by “several of [his] literary acquaintance” that his “not much exalted” prose was much more suitable to the “scene . . . laid in private life, and chiefly among those of middling rank.” For many, it seems, the bourgeoisie suffered in prose. But Johnson, Howard recalls, would have none of this:

Having communicated this to Dr. Samuel Johnson, his words (as well as I remember) were, “That he could hardly consider a prose Tragedy as dramatic . . . that let it be either in the middling or in low life, it may, though in metre and spirited, be properly familiar and colloquial; that, many in the middling rank are not without erudition; that they have the feelings and sensations of nature, and every emotion in consequence thereof, as well as the great, and that even the lowest, when impassioned, raise their language.”

Johnson’s argument tweaked the older, neoclassical assumption that poetic decorum mandates a correspondence between the language and social rank of a drama’s principal figures. Here a tragedy’s verse style has less to do with the nobility of those represented—as had been the case for John Dryden in An Essay on Dramatick Poesie (1668), where heroic rhyme’s “exalt[ation] above . . . common converse” images “the minds and fortunes of noble persons . . . exactly”—than with the intensity of the depicted afflictions. Tragedy needs verse not because its “elevation” allegorizes the status of its heroes, but because it corresponds to the magnitude of the drama’s subject matter, quite literally inscribing an emotional richness otherwise lost in the flatness of prose.

Johnson’s intervention plays out a mid-eighteenth-century discussion of the representation of emotion on the tragic stage, disclosing an unease with the degrading (if not also disenchanting) effects of prosaic suffering. Contemporaries in the period worried that prose was “fine and nervous,” disconcertingly “artless,” and “offensive,” while at the same time mere “trifling,” “below the dignity of Tragedy,” and even, for that reason, somehow “unnatural” in its expression. Consider, for example, that Johnson himself asserts that affliction “raises [one’s] language,” lapsing—naturally, he suggests—out of the grittiness of prose into the elegance of the poetic. A sort of poetry in the raw, suffering reaches after what’s already aesthetic and universal to misfortune, while prose trivializes and bogs down in the particular, rendering a tragedy “hardly dramatic,” untrue to the genre and affliction it purports to represent. Writing a few years later, Henry Mackenzie saw the genre’s strength as its ability to simulate those very same particulars, “the ordinary feelings and exertions of life” that nevertheless remained in tension with the tragic. In his view, suffering of this sort was if anything too true, its realism overburdening one’s perception. “Real distress, coming in a homely and unornamented state,” he concludes, “disgusts the eye.” Obscuring its art with disturbing efficacy, the outward formlessness of prosaic suffering threatened to neutralize the pleasures of the tragic.

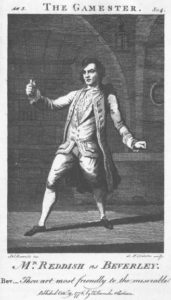

These concerns spoke to a moment of renewed interest in bourgeois and domestic tragedy, capping a period of formal experimentation in Britain, France, and Germany that Peter Gay claims was crucial to the Enlightenment’s “emancipation of art.” Beginning around the production of George Lillo’s landmark 1731 tragedy The London Merchant, a series of important works fashioned a new aesthetic idiom calibrated to “the ordinary feelings and exertions of life” by working through varieties of verse, prose, and the visual arts. Scholars have long cited Denis Diderot’s Le Fils naturel (1757) and Discours sur la poésie dramatique (1757) as well as G. E. Lessing’s Miss Sara Sampson (1755), Hamburgische Dramaturgie (1767–69), and Emilia Galotti (1772) as key moments in the drama’s modernization. But a variety of lesser-known works such as Charles Johnson’s prose Caelia; or The Perjur’d Lover (1732), Lillo’s 1736 encore to The London Merchant, Fatal Curiosity (which contemporaries claimed produced domestic interiors to horrifying effect in the cramped Little Haymarket theater), and Trauerspiele like Clementina von Poretta (1760; by Christoph Martin Wieland) and Clarissa (Johann Heinrich Steffens’s 1765 dramatization of Samuel Richardson’s novel) played with the representational mechanics of what one might call “ordinary suffering,” inhabiting familiar spaces and embodied emotion in ways that contemporaries took to be radical departures from established tragic convention. Among the most revolutionary of these innovations was the sustained use of prose, which until then had been largely confined to the domain of comedy. Indeed, in London, the 1770s and ’80s alone saw the production and publication of a number of prose tragedies, including notable revivals of The London Merchant and Edward Moore’s The Gamester (1753), curious adaptations such as The Fatal Interview (1782; a domestic tragic sequel to Pamela), quasi-gothic meditations on domestic violence like Richard Cumberland’s The Mysterious Husband (1783), as well as drames bourgeois in the form of Diderot’s 1758 Le Père de famille (translated “by a lady” as The Family Picture in 1781) and Louis-Sébastien Mercier’s L’Indigent (1772; translated in London and Edinburgh as The Distressed Family in 1787). Despite the concerns of those like Johnson and Mackenzie, by the latter half of the century, a deft use of prose on the stage could render the theater uncannily intimate, calling forth a space where private woe played out for all to see.

In what follows, I want to explore the affective stakes of this turn to prosaic suffering. Or rather more precisely, I want to trace a line through the contested process by which suffering became prosaic in eighteenth-century bourgeois and domestic drama in order to draw some implications for the history of emotion and the dialectics of realism at midcentury. My claim is that the emergence of prosaic suffering on the period’s tragic stage helps to imagine modern forms of affliction, thereby navigating a range of confessedly “ordinary” feelings by evoking and engaging and testing them across page and stage. Unlike the “heroick suffering” of classical, pathetic, or otherwise “high” tragic forms prevalent at the earlier part of the century, prosaic suffering performed its grief with troubling immediacy and a raw intensity, in ways that were personal and familiar, absorptive rather than theatrical, and provocatively disenchanted in their implications. Prosaic suffering presents the tragic figure as an emblem of abandonment, in which (as Georg Lukács claimed of the novel) everyday life is experienced as simultaneously leaden and trivial. I anchor my discussion in a close reading of Moore’s The Gamester, a drama whose importance to the development of realism was well known in the eighteenth century, and whose use of prose at midcentury tracks this shift in suffering most clearly, though by no means exclusively (as will become clear). Adapting the novel’s “writing to the moment” for the theater, (a method almost certainly absorbed in Moore’s reading of Clarissa and correspondence with Richardson on the novel’s formal effects), prose conferred a lively presence upon the performance of suffering, in ways that denied its spectators the sort of rhetorical elevation that stood in for transcendence. In making this case, therefore, I place the practices of British bourgeois tragedy in dialogue with contemporary performance and aesthetic theory so as to reconstruct the terrain of emotion’s exploration onstage. If, as one critic has claimed, versification serves to beautify the experience of suffering, prose insists on its crude intolerability, its reality and resistance to poetic gilding. Continue reading …

This essay looks to bourgeois tragedy’s use of prose in the mid-eighteenth century as an episode in the histories of realism and emotion, arguing that the emergence of prosaic suffering on the period’s tragic stage helps to imagine modern forms of affliction. Taking Edward Moore’s 1753 drama The Gamester as emblematic of this shift, and situating the text in its performative and aesthetic contexts, I trace the “emotional practices” that navigated a range of confessedly “ordinary” feelings by evoking, engaging, and testing them across page and stage. Performing its grief with troubling immediacy and a raw intensity, in ways that were personal and familiar, absorptive rather than theatrical, and provocatively disenchanted, bourgeois tragedy thereby embodied a middling mode of existence in which the prosaic qualified not only the drama’s form but also, ultimately, its content.

ALEX ERIC HERNANDEZ is Assistant Professor of English at the University of Toronto, where he works on Restoration and eighteenth-century literature and culture. This essay is part of his book in progress titled Modernity and Affliction: The Making of British Bourgeois Tragedy.

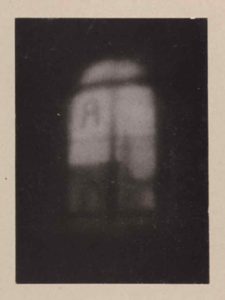

In 1891, the Viennese physiologist Sigmund Exner published the first comprehensive study of complex, multifaceted eyes. Today, his book The Physiology of the Compound Eyes of Insects and Crustaceans is a classic in its field. Scholars still refer to Exner’s findings, even if “it took the scientific community 80 years to catch up with his state of knowledge.” The most popular outcome of Exner’s studies was a picture proudly printed opposite the title page. According to the caption, the figure shows “the erect retinal image in the eye of the firefly (Lampyris spldl.).” The original photograph was made with the help of Josef Maria Eder, author of the Handbuch der Photographie and renowned director of the Viennese Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt (Academy of graphic arts). Eder placed the eye—fully stripped of all tissue behind the lens structure—under a microphotographic apparatus, focused on the plane almost directly behind the inner endings of the ommatidia, and then recorded the image that would have formed at this point on the removed retinal layer. The resulting photograph shows the window of the laboratory room; the letter R, slightly distorted, mounted on one of its panes; and finally, beyond the pane, the “Schottenfeld Church and church tower, approximately several hundred paces distant” from the laboratory. This, at least, is what a human observer notices when studying the picture. Far more questionable is what the glowworm might see. Even if the photograph exactly reproduces the image “which the eye of the glowworm beholds,” as Eder claimed, it is not at all clear whether the resulting impression is comparable to the one perceived by a human being, and, even less clear, whether we can suppose that seeing always takes place in the same way.

In 1891, the Viennese physiologist Sigmund Exner published the first comprehensive study of complex, multifaceted eyes. Today, his book The Physiology of the Compound Eyes of Insects and Crustaceans is a classic in its field. Scholars still refer to Exner’s findings, even if “it took the scientific community 80 years to catch up with his state of knowledge.” The most popular outcome of Exner’s studies was a picture proudly printed opposite the title page. According to the caption, the figure shows “the erect retinal image in the eye of the firefly (Lampyris spldl.).” The original photograph was made with the help of Josef Maria Eder, author of the Handbuch der Photographie and renowned director of the Viennese Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt (Academy of graphic arts). Eder placed the eye—fully stripped of all tissue behind the lens structure—under a microphotographic apparatus, focused on the plane almost directly behind the inner endings of the ommatidia, and then recorded the image that would have formed at this point on the removed retinal layer. The resulting photograph shows the window of the laboratory room; the letter R, slightly distorted, mounted on one of its panes; and finally, beyond the pane, the “Schottenfeld Church and church tower, approximately several hundred paces distant” from the laboratory. This, at least, is what a human observer notices when studying the picture. Far more questionable is what the glowworm might see. Even if the photograph exactly reproduces the image “which the eye of the glowworm beholds,” as Eder claimed, it is not at all clear whether the resulting impression is comparable to the one perceived by a human being, and, even less clear, whether we can suppose that seeing always takes place in the same way.

Michael Lucey’s translation of

Michael Lucey’s translation of  In this original and engaging work, Kent Puckett looks at how British filmmakers imagined, saw, and sought to represent its war during wartime through film. The Second World War posed unique representational challenges to Britain’s filmmakers. Because of its logistical enormity, the unprecedented scope of its destruction, its conceptual status as total, and the way it affected everyday life through aerial bombing, blackouts, rationing, and the demands of total mobilization, World War II created new, critical opportunities for cinematic representation.

In this original and engaging work, Kent Puckett looks at how British filmmakers imagined, saw, and sought to represent its war during wartime through film. The Second World War posed unique representational challenges to Britain’s filmmakers. Because of its logistical enormity, the unprecedented scope of its destruction, its conceptual status as total, and the way it affected everyday life through aerial bombing, blackouts, rationing, and the demands of total mobilization, World War II created new, critical opportunities for cinematic representation.