Powers of the Script: Prescription and Performance in Turn-of-the-Century France

by Antoine Lentacker

For all their concern with the nature of medical authority, historians of medicine have paid remarkably little attention to the history of the medical script, the main medium in and through which the doctor’s authority is enacted. This essay analyzes the medical prescription as an instance of a written performative. While focusing on the changing uses of one particular documentary genre in turn-of-the-twentieth-century France, it seeks to outline a broader theory of graphic performativity, or of the conditions under which the symbolic power of the oral performance is transferred and transformed as it is transcribed on paper.

The essay begins:

Although a somewhat stern personality, Paul Brouardel, dean of the Paris School of Medicine, enjoyed an occasional night out at the theater. On one such night in the late 1890s he had found himself particularly entertained by a vaudeville scene that had some relevance to his line of work, so he decided to relate it to his students. That scene, in his summary, involved an on-duty physician at a fictive theater who, longing for a night off, left his seat to a friend who was a stranger to the medical arts. By a stroke of fate, a young lady in attendance that night finds herself unwell, and all eyes turn toward the man occupying the on-call doctor’s seat. Put on the spot, the doctor’s friend quickly realizes he has no way out, so he rushes to the patient’s side, unlaces her corset, and, for good measure, pretends to write up a prescription, scribbling a few words without rhyme or reason on a slip of paper and signing it as illegibly as he could. While the ink is still drying, the script is snatched out of his hands and an usher is dispatched with it to the nearest pharmacy. Thankfully, the potion he returns with has the effect everyone counts on, and the indisposed spectator promptly recovers her health.

How are we to interpret such a scene? Is it that the prescription is useless? If a cure can be effected with a prescription that is senseless, illegible, and apocryphal—hence flawed in all the ways that seem to matter—what added value, we might ask, is there in the proper prescriptions of licensed and qualified physicians? Or is it on the contrary that the prescription does it all? That the accuracy of the diagnosis and the nature of the drug prescribed matter less in achieving the desired effect than the ritual of the prescription itself? Brouardel did not tell his students. Instead, he deemed the story “very fitting in a comedy, but not so in practice” and proceeded to lecture his audience on the need to write prescriptions clearly and legibly. Only later, in an article of 1905, did he appear to ponder what might have been the implicit lesson of the comedy he had delighted in ten years earlier:

The first source of the efficacy of the physician’s action is the trust that the sick place in him. The patient complies with and fulfills prescriptions in whole only if he surrenders completely to the authority of his physician. Trust sustains his moral fortitude; moral fortitude acts upon physiological processes; hope restores strength and resilience in the struggle against disease. The lack of trust has the opposite effect. Prescriptions fail to be fully observed; despair takes hold of the patient and recovery is compromised.

This essay follows Brouardel’s lead in accounting for the double nature of the prescription as both a drug to be consumed and an order to be trusted and obeyed. While suspending judgment on his psychophysiological speculations, it also sees the efficacy of the prescription as residing in an alchemy of words and gestures as much as in a chemistry of substances, and it sets out to describe what this symbolic efficacy owes to the form and medium in which the prescription is administered.

To name and analyze the symbolic powers of the medical script, I shall argue, we need a concept of graphic performativity. In elaborating this concept, two main pitfalls ought to be eschewed. The first mistake would be to locate the powers of performative speech in speech itself rather than in the relations of power between speakers and their addressees. Instead, we need to understand performativity as John Austin originally did—namely, as a theory of ritual whose efficacy is linked to a number of sociohistorical, as well as linguistic, conditions. Of the “conditions of felicity” of performative speech, the first to be mentioned in How to Do Things with Words is the “position of the speaker”: to produce its effect, ritual speech must be delivered by the “person appointed” to do so. Socially efficacious speech, in other words, is inseparable from the casts of socially codified roles in which speech is produced. In this sense, a theory of the performative speaks to the vaudeville scene Brouardel related to his students. The prescription in that instance worked its magic only because its author was, quite literally, in the doctor’s place, and also of course because he was a man of a certain age and poise, the sort of man who could claim doctors among his friends. Furthermore, it speaks to a rich historiography on the changing roles of doctors, patients, and (to a lesser degree) pharmacists in nineteenth-century medicine, a body of work in which few subjects have been as thoroughly investigated as has the struggle of an institutionalized medical profession for the exclusive authority to diagnose and to prescribe.

The opposite pitfall, however, would be to view the script as merely registering or reflecting relations of power constituted elsewhere and by other means. Authority is relational, and so it ought to be examined through its media as well as through its figures or possessors. On this the historiography has less to offer. For all their interest in the deployment of professional authority, medical historians have left the prescription, the main medium in and through which the doctor’s authority is expressed and enacted, virtually unattended. And so does Austin, whose performatives are typically oral performances engaging a kind of spectacle of the speech act. While there is no doubt that prescribing is a performative in Austin’s sense, a speech act whose proper performance endows words with a certain binding force and validity, it is an act deposited in a graphic artifact and mediated by it. Once the patient walks away from the stage of the medical consultation, the performance is over and only a script remains. Hence the specific question here is: How to do things with written words? As a general rule, writing frees the powers of speech from the body of the speaker, even as it threatens to undermine these powers by severing the link to the performance and performer from which they emanate. This means that there are specific conditions of felicity to the written performative—and specific ways it can go wrong.

By graphic performativity, then, I refer to the ways in which the graphic artifact captures and transforms the powers of the oral performance as it is transcribed on paper. My argument takes aim throughout at what might be termed a fetishism of the document. Documents do not attest, authorize, or document on their own, but only within shifting scriptural usages, practices, and institutions. To illustrate this point, I focus on one specific moment in the history of the medical script and examine it from the viewpoint of the three main figures involved in acting it out—physicians, pharmacists, and patients. The special attention the genre attracted in fin de siècle France resulted from the rise of a vast proprietary drug industry whose products were advertised in newspapers and available over the counter. France was not unique in this, but, for reasons explained in the first section of the essay, it was exemplary. French physicians during this period registered with unique acuity the erosive effects of printed medical advice on the authority of the script. Their conversations on the subject generated the trove of sources on which this essay relies. The next two sections consider the matter from the perspective of the pharmacist who judges the validity of the doctor’s note. This allows for a description of some of the concrete ways in which the script creates or loses a connection to the original scene of its production. The final section returns to the effect of the prescription on the patient. Its goal is to reveal the script as a medium in which the subject positions of physician and patient were not merely mirrored but also at once made, maintained, and destabilized. Continue reading …

ANTOINE LENTACKER is Assistant Professor of History at the University of California, Riverside. His work is broadly dedicated to investigating the effects of changing communication technologies on the governing of people and things in Europe since 1800.

ANTOINE LENTACKER is Assistant Professor of History at the University of California, Riverside. His work is broadly dedicated to investigating the effects of changing communication technologies on the governing of people and things in Europe since 1800.

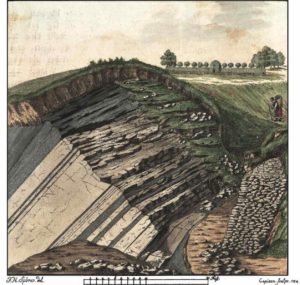

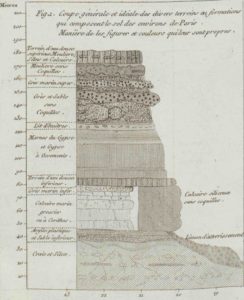

Decorative elements borrowed from topographical landscape drawing have been abandoned, and the human figure is excluded altogether. Instead, rock strata are organized along a vertical axis whose annotations reflect both their relative depth and the geological era in which they were thought to have formed. In late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century stratigraphic diagrams, geological history came into view for the first time, pictured as a function of depth.

Decorative elements borrowed from topographical landscape drawing have been abandoned, and the human figure is excluded altogether. Instead, rock strata are organized along a vertical axis whose annotations reflect both their relative depth and the geological era in which they were thought to have formed. In late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century stratigraphic diagrams, geological history came into view for the first time, pictured as a function of depth. Atop the rock, man. The German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich, known for his love of the Harz Mountains, pictured a strikingly different early nineteenth-century encounter between the human and the geological in his Wanderer Above a Sea of Clouds. From a granite outcropping, an eponymous wanderer placidly surveys the rocky mountain formations shrouded in mist below him and the faintly rendered peaks that flicker into view in the distance. The figure’s physical elevation over his environment and his panoramic view suggest the fantasy of a geological landscape visually possessed and perhaps also physically mastered by the human subject. Long used as a kind of art-historical shorthand for European Romanticism in general, the painting has more recently been taken as emblematic of a model of early nineteenth-century bourgeois subjectivity concomitant with the rise of modern spectatorial practices: “the ascendancy of newly realized bourgeois aspirations, fantasies of autonomy” that, Jonathan Crary writes, “permitted at least an optical appropriation” of the natural world, if not a literal one. Like Crary’s, a number of influential accounts of the painting grant interpretive priority to how the painting frames the role and status of the human figure qua a perceptual encounter with nature, whether mediated or direct.

Atop the rock, man. The German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich, known for his love of the Harz Mountains, pictured a strikingly different early nineteenth-century encounter between the human and the geological in his Wanderer Above a Sea of Clouds. From a granite outcropping, an eponymous wanderer placidly surveys the rocky mountain formations shrouded in mist below him and the faintly rendered peaks that flicker into view in the distance. The figure’s physical elevation over his environment and his panoramic view suggest the fantasy of a geological landscape visually possessed and perhaps also physically mastered by the human subject. Long used as a kind of art-historical shorthand for European Romanticism in general, the painting has more recently been taken as emblematic of a model of early nineteenth-century bourgeois subjectivity concomitant with the rise of modern spectatorial practices: “the ascendancy of newly realized bourgeois aspirations, fantasies of autonomy” that, Jonathan Crary writes, “permitted at least an optical appropriation” of the natural world, if not a literal one. Like Crary’s, a number of influential accounts of the painting grant interpretive priority to how the painting frames the role and status of the human figure qua a perceptual encounter with nature, whether mediated or direct. England’s Parnassus has long been studied for what it includes. Published in 1600, the printed commonplace book culls together passages from Philip Sidney, Edmund Spenser, Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare, and other lodestars of its fin de siècle moment. The inclusion of such vernacular authors sets England’s Parnassus apart from the commonplace books that came before it, which anthologized only writers of classical antiquity. It also aligns the volume with more recently printed commonplace books, like Francis Meres’s Palladis Tamia (1598) and John Bodenham’s Bel-vedere, or The Garden of the Muses (1600), which collectively ushered in what Zachary Lesser and Peter Stallybrass have called “a novel conception of commonplacing,” whereby “‘Moderne and extent Poets,’ who wrote in the culturally and geographically marginal vernacular of English, [are treated] as suitable authorities on which to base an entire commonplace book.” But England’s Parnassus is just as notable for what it leaves out. When the coy Adonis, in Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis, resists the advances of the goddess of love, he protests by urging her to “Call it not love, since love to heaven is fled, / Since sweating lust on earth usurped the name.” It is just one of the many aphorisms from the poem that Robert Allott, the book’s editor, excerpts. But that is not quite how the passage goes in England’s Parnassus. “—Love to heaven is fled,” it reads, “Since sweating lust on earth usurpt the name.” As a heavy dash effaces the metalanguage that begins Adonis’s pronouncement, England’s Parnassus offers an early modern example of the transcultural tendency, documented by Greg Urban, for transcriptions to delete the metalanguage that marks them as transcribable in the first place, “as if the metadiscursive portions of the discourse were invisible (or inaudible) and yet capable of exercising an effect.”

England’s Parnassus has long been studied for what it includes. Published in 1600, the printed commonplace book culls together passages from Philip Sidney, Edmund Spenser, Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare, and other lodestars of its fin de siècle moment. The inclusion of such vernacular authors sets England’s Parnassus apart from the commonplace books that came before it, which anthologized only writers of classical antiquity. It also aligns the volume with more recently printed commonplace books, like Francis Meres’s Palladis Tamia (1598) and John Bodenham’s Bel-vedere, or The Garden of the Muses (1600), which collectively ushered in what Zachary Lesser and Peter Stallybrass have called “a novel conception of commonplacing,” whereby “‘Moderne and extent Poets,’ who wrote in the culturally and geographically marginal vernacular of English, [are treated] as suitable authorities on which to base an entire commonplace book.” But England’s Parnassus is just as notable for what it leaves out. When the coy Adonis, in Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis, resists the advances of the goddess of love, he protests by urging her to “Call it not love, since love to heaven is fled, / Since sweating lust on earth usurped the name.” It is just one of the many aphorisms from the poem that Robert Allott, the book’s editor, excerpts. But that is not quite how the passage goes in England’s Parnassus. “—Love to heaven is fled,” it reads, “Since sweating lust on earth usurpt the name.” As a heavy dash effaces the metalanguage that begins Adonis’s pronouncement, England’s Parnassus offers an early modern example of the transcultural tendency, documented by Greg Urban, for transcriptions to delete the metalanguage that marks them as transcribable in the first place, “as if the metadiscursive portions of the discourse were invisible (or inaudible) and yet capable of exercising an effect.” MATTHEW HUNTER

MATTHEW HUNTER How is the present-day return to Marx a different one from that of global 1968? A renewed interest in political economy is leading cultural critics and social theorists to ask fundamental questions about how capital reproduces itself both through and beyond the wage relation: how it makes and unmakes classes across modes of production, creates surplus and disposable populations that are racialized and gendered, and requires both unexploited and waste spaces, in its quest to produce value.

How is the present-day return to Marx a different one from that of global 1968? A renewed interest in political economy is leading cultural critics and social theorists to ask fundamental questions about how capital reproduces itself both through and beyond the wage relation: how it makes and unmakes classes across modes of production, creates surplus and disposable populations that are racialized and gendered, and requires both unexploited and waste spaces, in its quest to produce value. In 2011, artist Khvay Samnang offered “piggyback” rides to residents and visitors of the White Building in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, as part of his performance piece, Samnang Cow Taxi. Titled colloquially with his given name, it was a humble undertaking. Khvay wore handmade cow horns (fig. 1) and, despite his svelte frame, humorously carried people on his back as if he were a robust workhorse. Evoking the water buffalo, a laboring animal crucial to Cambodian agricultural practices, seemed an odd choice for someone ferrying people around the more urban setting of the White Building. Moreover, the taxi ride seemed to grant a touristic gaze for nonresidents of the dilapidated public housing complex. Yet the physical intimacy of the gesture, as well as the slowness and toil of it, lent a critical edge to the playful jaunt around the famous white apartment structure, transformed into a muddy gray from decades of neglect. The White Building was erected in 1963 as a modernist, utopian experiment in public housing. It was created soon after Cambodia’s independence in 1953 as part of a socially optimistic, homegrown wave of New Khmer Architecture, and it was intended to house civil servants and municipal workers. After the devastating Khmer Rouge regime collapsed in 1979, many returned to the city in need of housing, and the modest apartments were repopulated with dancers, musicians, artists, and filmmakers. Khvay’s own practice has been deeply indebted to the site and people of the White Building, and his slow, caring, arduous gesture highlighted a community of residents who, like the building itself, have been historically subject to state neglect, inattention, and habitual violence.

In 2011, artist Khvay Samnang offered “piggyback” rides to residents and visitors of the White Building in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, as part of his performance piece, Samnang Cow Taxi. Titled colloquially with his given name, it was a humble undertaking. Khvay wore handmade cow horns (fig. 1) and, despite his svelte frame, humorously carried people on his back as if he were a robust workhorse. Evoking the water buffalo, a laboring animal crucial to Cambodian agricultural practices, seemed an odd choice for someone ferrying people around the more urban setting of the White Building. Moreover, the taxi ride seemed to grant a touristic gaze for nonresidents of the dilapidated public housing complex. Yet the physical intimacy of the gesture, as well as the slowness and toil of it, lent a critical edge to the playful jaunt around the famous white apartment structure, transformed into a muddy gray from decades of neglect. The White Building was erected in 1963 as a modernist, utopian experiment in public housing. It was created soon after Cambodia’s independence in 1953 as part of a socially optimistic, homegrown wave of New Khmer Architecture, and it was intended to house civil servants and municipal workers. After the devastating Khmer Rouge regime collapsed in 1979, many returned to the city in need of housing, and the modest apartments were repopulated with dancers, musicians, artists, and filmmakers. Khvay’s own practice has been deeply indebted to the site and people of the White Building, and his slow, caring, arduous gesture highlighted a community of residents who, like the building itself, have been historically subject to state neglect, inattention, and habitual violence.

Since the drug war’s inception in 2006, organized and disorganized violence has claimed approximately 200,000 lives in Mexico, and more than 30,000 people have “disappeared.” In the thirteen years that have transpired since then, more people have been killed in Mexico’s war than in the US invasion of Iraq, and more have been forcibly “disappeared” than during Argentina’s Dirty War. Illegal economies have been revolutionized along the way, in processes that Natalia Mendoza has called “cartelization,” which started with the privatization of trade routes for illegal border traffic, most notably of drugs and migrants, and with the development of a bureaucracy within the illegal economy. Contrary to the general prejudice, “cartels” are not reliant on trade in illegal drugs in any transcendental sense; they rely essentially on the armed privatization of public space, the ransom of public liberties, and the forcible appropriation of public goods.

Since the drug war’s inception in 2006, organized and disorganized violence has claimed approximately 200,000 lives in Mexico, and more than 30,000 people have “disappeared.” In the thirteen years that have transpired since then, more people have been killed in Mexico’s war than in the US invasion of Iraq, and more have been forcibly “disappeared” than during Argentina’s Dirty War. Illegal economies have been revolutionized along the way, in processes that Natalia Mendoza has called “cartelization,” which started with the privatization of trade routes for illegal border traffic, most notably of drugs and migrants, and with the development of a bureaucracy within the illegal economy. Contrary to the general prejudice, “cartels” are not reliant on trade in illegal drugs in any transcendental sense; they rely essentially on the armed privatization of public space, the ransom of public liberties, and the forcible appropriation of public goods. CLAUDIO LOMNITZ

CLAUDIO LOMNITZ