The Uses of Genre: Is There an “Adam Smith Question”?

by Ryan Healey, Ewan Jones, Paul Nulty, Gabriel Recchia, John Regan, and Peter de Bolla

The essay begins:

This paper sets out a novel computational method of testing the uses to which generic membership can be put to help us understand large-scale movements in the history of ideas. It does so by taking a well-known test case, the so-called Adam Smith Question, as an easily identifiable (and well-researched) problem in generic consistency. In brief, the problem is this: Smith proposes one version of human nature based on sympathy in his Theory of Moral Sentiments (TMS) and another, completely orthogonal to it, based on self-interest in his Wealth of Nations (WN). This incoherence (if one assumes that Smith worked hard at creating a unified theory of human nature, which in itself is contestable) is said to be one of genre, the difference between moral philosophy and political economy.

The wider context of Smith’s intellectual project—let us say the second half of the British eighteenth century—also provides us with a background in which the question of genre is itself problematic or undergoing conceptual construction. It has long been recognized that over the course of the century the contours of emerging genres—for example, prose fiction, political economy, moral philosophy, aesthetics—would ossify around different and sometimes contradictory sets of moral, social, and epistemological premises. Literary critics have largely investigated this generic instability via the conspicuously hybrid genre of the novel, with particular attention to the early novel’s seeming inattention to modern distinctions of “fact” and “fiction,” within what Mary Poovey calls the “fact/fiction continuum.”

A significant fellow traveler in this epistemological crisis can be identified in the uneven and incompatible development of concepts of economic morality across different genres that might be termed the “self-society continuum.” In Commerce, Morality, and the Eighteenth-Century Novel, Liz Bellamy argues that economic texts privileged the second term, “society,” as they compressed individuals and their personal faculties into an indiscriminate mass of homo economicus, while, conversely, contemporaneous texts of moral philosophy addressed a unique individual steeped in elite civic humanist rhetoric that exempted him or her from the rational maximization of money and naked self-interest. The new commercial morality was understood as peculiar, destructive, and “far from being overwhelmingly accepted or embraced” by ruling classes whose traditionalism could not easily comprehend and accommodate the burgeoning intangible property of financial instruments. This unease was then reflected then reflected in a parallel discordance between works of moral philosophy and the fledgling genre of economics. Bellamy explicitly identifies this inconsistency in generically separate works by David Hume and Smith, who seem to void the ethical directives of their moral philosophy with their economic texts and vice versa.

Yet “negates” is perhaps too strong a way of putting things. After thirty years without significantly revising the work, Smith began to alter TMS in the last year of his life, adding a sixth part titled “Of the Character of Virtue” that “appealed to the citizenry to place the interests of society ahead of the interest of any faction to which they might be attached.” Crucially, however, this revision did not radically alter the precepts of the theory to align more explicitly with the selfish personality exhibited by WN. For Smith, there seems never to have been an urgent need to bring the two works into dialogue. To complicate matters still further, the alleged contradiction may well arise, at least in part, from the anachronistic imposition of generic differences that at the time were not perceivable. What would only later be recognized as political economy was still, at the point of Smith’s writing, in the process of coming into being. As Margaret Schabas notes, “Economic phenomena were viewed as contiguous with physical nature” up until the mid-nineteenth century, when the notion of “the economy” as a delimited entity first arose.

It is in large part due to these complex compositional, generic, and historical contexts that scholars have, over the past three decades, increasingly tired of the Adam Smith Problem, with its binary options. In 1998, Amos Witztum declared briskly that, “for modern readers this is not a real problem.” More recently, David Wilson and William Dixon claimed, “The old Das Adam Smith Problem is no longer tenable. Few today believe that Smith postulates two contradictory principles of human action.” Close readings of the concepts of sympathy, prudence, and self-interest in TMS and WN have led critics to conclude that Smith does not openly recommend two polar opposite theories of human motivation, albeit “there is still no widely agreed version of what it is that links these two texts, aside from their common author; no widely agreed version of how, if at all, Smith’s postulation of self-interest as the organizing principle of economic activity fits in with his wider moral-ethical concerns.”

This paper applies a novel computational mode of analysis to the large question of genre and to the more specific issues that arise in Smith’s work. We do so, however, not to flog the dead horse of das Adam Smith Problem; we do not believe that such a debate could ever be decisively “settled” one way or another. We do, however, believe that the computational analysis of large corpora (and subcorpora) permit us to discern both the continuities and discontinuities of conceptual usage across different works—continuities and discontinuities to which more standard modes of intellectual history, for all their many virtues, remain blind. We thus interrogate two interlocking questions: first, to what extent does the sympathy so cardinal to TMS, and the self-interest so essential to WN, participate in broader conceptual networks, whose existence is statistically verifiable? Second, to what extent do such local continuities or discontinuities prove representative of broader generic differences in the culture at large? Chief among the virtues of such a computational approach, we believe, is the critical vantage it offers with regard to genre. Rather than simply accepting the markers that authors or publishers apply to the texts at hand (“political economy,” and so on), we use patterns of lexical collocation to investigate whether such distinctions are indeed valid. Continue reading …

In this article authors Ryan Healey, Ewan Jones, Paul Nulty, Gabriel Recchia, and John Regan join Peter de Bolla in using the methodologies of de Bolla’s The Architecture of Concepts to uncover the complex conceptual networks in which lexical items are embedded. For de Bolla, because concepts are “units of ‘thinking’ that cannot be expressed in words without remainder,” they may be stretched across constellations of collocations circulating in a “common unshareable” domain of the textual culture at large.

PETER DE BOLLA is Professor of Cultural History and Aesthetics at the University of Cambridge where he also directed the Cambridge Concept Lab. His most recent monograph is The Architecture of Concepts: The Historical Formation of Human Rights (Fordham University Press, 2013), and he is currently writing a book on the artist Pierre Bonnard.

The Hungarian-born French painter

The Hungarian-born French painter  is a Junior Research Fellow at King’s College, University of Cambridge. Her research interests include postwar German art, the impact of technology on painting, and digital art. She is currently completing a book on Gerhard Richter.

is a Junior Research Fellow at King’s College, University of Cambridge. Her research interests include postwar German art, the impact of technology on painting, and digital art. She is currently completing a book on Gerhard Richter. Using John Lockwood Kipling’s Beast and Man in India (1891) as her text, Parama Roy examines the encounter of two contrasting economies of animal protection and animal cruelty, especially Kipling’s understanding of carnivory as the basis not only for human sociability but also of kindness to the nonhuman.

Using John Lockwood Kipling’s Beast and Man in India (1891) as her text, Parama Roy examines the encounter of two contrasting economies of animal protection and animal cruelty, especially Kipling’s understanding of carnivory as the basis not only for human sociability but also of kindness to the nonhuman.

The coincidence of the Trump presidency in the United States and the upsurge of rightwing movements in Europe, including Alternativ für Deutschland, make this an appropriate moment for reconsidering Ernst Cassirer’s analysis of fascism in the last chapter of The Myth of the State. Composed in the 1940s, when Cassirer was in the United States, and published posthumously in 1946, The Myth of the State was Cassirer’s last and most explicitly political work. In this work he suggested that the right lens for thinking about authoritarian political movements was myth, not the organic myth of earlier primitive cultures but instead the manufactured myth of late capitalism, which involved the appeal to irrational instincts and the manipulation of symbols. At the same time, Cassirer held on to the possibility of a rational critique of fascism. In our current era of such manufactured myths as “fake news” and “the caravan,” it is worth reflecting on an earlier historical moment when Cassirer confronted the manufactured myths of the Nazi state and offered a defense of rationality missing from much of our current political conversation. In this essay, I explore the basis of Cassirer’s surprising optimism, which I argue has to do not simply with his “symbolic turn,” his critique of neo-Kantianism for its neglect of language and other symbolic systems in shaping human experience, but with his recovery of art as central to the human capacity for critical thinking and his linking of this capacity to the survival of Jewish ethical traditions.

The coincidence of the Trump presidency in the United States and the upsurge of rightwing movements in Europe, including Alternativ für Deutschland, make this an appropriate moment for reconsidering Ernst Cassirer’s analysis of fascism in the last chapter of The Myth of the State. Composed in the 1940s, when Cassirer was in the United States, and published posthumously in 1946, The Myth of the State was Cassirer’s last and most explicitly political work. In this work he suggested that the right lens for thinking about authoritarian political movements was myth, not the organic myth of earlier primitive cultures but instead the manufactured myth of late capitalism, which involved the appeal to irrational instincts and the manipulation of symbols. At the same time, Cassirer held on to the possibility of a rational critique of fascism. In our current era of such manufactured myths as “fake news” and “the caravan,” it is worth reflecting on an earlier historical moment when Cassirer confronted the manufactured myths of the Nazi state and offered a defense of rationality missing from much of our current political conversation. In this essay, I explore the basis of Cassirer’s surprising optimism, which I argue has to do not simply with his “symbolic turn,” his critique of neo-Kantianism for its neglect of language and other symbolic systems in shaping human experience, but with his recovery of art as central to the human capacity for critical thinking and his linking of this capacity to the survival of Jewish ethical traditions. VICTORIA KAHN

VICTORIA KAHN

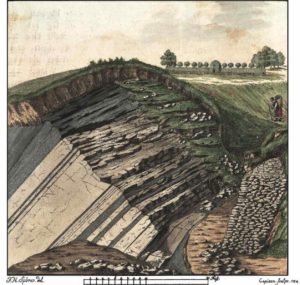

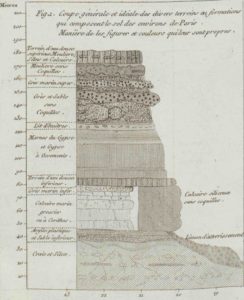

Decorative elements borrowed from topographical landscape drawing have been abandoned, and the human figure is excluded altogether. Instead, rock strata are organized along a vertical axis whose annotations reflect both their relative depth and the geological era in which they were thought to have formed. In late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century stratigraphic diagrams, geological history came into view for the first time, pictured as a function of depth.

Decorative elements borrowed from topographical landscape drawing have been abandoned, and the human figure is excluded altogether. Instead, rock strata are organized along a vertical axis whose annotations reflect both their relative depth and the geological era in which they were thought to have formed. In late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century stratigraphic diagrams, geological history came into view for the first time, pictured as a function of depth. Atop the rock, man. The German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich, known for his love of the Harz Mountains, pictured a strikingly different early nineteenth-century encounter between the human and the geological in his Wanderer Above a Sea of Clouds. From a granite outcropping, an eponymous wanderer placidly surveys the rocky mountain formations shrouded in mist below him and the faintly rendered peaks that flicker into view in the distance. The figure’s physical elevation over his environment and his panoramic view suggest the fantasy of a geological landscape visually possessed and perhaps also physically mastered by the human subject. Long used as a kind of art-historical shorthand for European Romanticism in general, the painting has more recently been taken as emblematic of a model of early nineteenth-century bourgeois subjectivity concomitant with the rise of modern spectatorial practices: “the ascendancy of newly realized bourgeois aspirations, fantasies of autonomy” that, Jonathan Crary writes, “permitted at least an optical appropriation” of the natural world, if not a literal one. Like Crary’s, a number of influential accounts of the painting grant interpretive priority to how the painting frames the role and status of the human figure qua a perceptual encounter with nature, whether mediated or direct.

Atop the rock, man. The German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich, known for his love of the Harz Mountains, pictured a strikingly different early nineteenth-century encounter between the human and the geological in his Wanderer Above a Sea of Clouds. From a granite outcropping, an eponymous wanderer placidly surveys the rocky mountain formations shrouded in mist below him and the faintly rendered peaks that flicker into view in the distance. The figure’s physical elevation over his environment and his panoramic view suggest the fantasy of a geological landscape visually possessed and perhaps also physically mastered by the human subject. Long used as a kind of art-historical shorthand for European Romanticism in general, the painting has more recently been taken as emblematic of a model of early nineteenth-century bourgeois subjectivity concomitant with the rise of modern spectatorial practices: “the ascendancy of newly realized bourgeois aspirations, fantasies of autonomy” that, Jonathan Crary writes, “permitted at least an optical appropriation” of the natural world, if not a literal one. Like Crary’s, a number of influential accounts of the painting grant interpretive priority to how the painting frames the role and status of the human figure qua a perceptual encounter with nature, whether mediated or direct. England’s Parnassus has long been studied for what it includes. Published in 1600, the printed commonplace book culls together passages from Philip Sidney, Edmund Spenser, Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare, and other lodestars of its fin de siècle moment. The inclusion of such vernacular authors sets England’s Parnassus apart from the commonplace books that came before it, which anthologized only writers of classical antiquity. It also aligns the volume with more recently printed commonplace books, like Francis Meres’s Palladis Tamia (1598) and John Bodenham’s Bel-vedere, or The Garden of the Muses (1600), which collectively ushered in what Zachary Lesser and Peter Stallybrass have called “a novel conception of commonplacing,” whereby “‘Moderne and extent Poets,’ who wrote in the culturally and geographically marginal vernacular of English, [are treated] as suitable authorities on which to base an entire commonplace book.” But England’s Parnassus is just as notable for what it leaves out. When the coy Adonis, in Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis, resists the advances of the goddess of love, he protests by urging her to “Call it not love, since love to heaven is fled, / Since sweating lust on earth usurped the name.” It is just one of the many aphorisms from the poem that Robert Allott, the book’s editor, excerpts. But that is not quite how the passage goes in England’s Parnassus. “—Love to heaven is fled,” it reads, “Since sweating lust on earth usurpt the name.” As a heavy dash effaces the metalanguage that begins Adonis’s pronouncement, England’s Parnassus offers an early modern example of the transcultural tendency, documented by Greg Urban, for transcriptions to delete the metalanguage that marks them as transcribable in the first place, “as if the metadiscursive portions of the discourse were invisible (or inaudible) and yet capable of exercising an effect.”

England’s Parnassus has long been studied for what it includes. Published in 1600, the printed commonplace book culls together passages from Philip Sidney, Edmund Spenser, Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare, and other lodestars of its fin de siècle moment. The inclusion of such vernacular authors sets England’s Parnassus apart from the commonplace books that came before it, which anthologized only writers of classical antiquity. It also aligns the volume with more recently printed commonplace books, like Francis Meres’s Palladis Tamia (1598) and John Bodenham’s Bel-vedere, or The Garden of the Muses (1600), which collectively ushered in what Zachary Lesser and Peter Stallybrass have called “a novel conception of commonplacing,” whereby “‘Moderne and extent Poets,’ who wrote in the culturally and geographically marginal vernacular of English, [are treated] as suitable authorities on which to base an entire commonplace book.” But England’s Parnassus is just as notable for what it leaves out. When the coy Adonis, in Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis, resists the advances of the goddess of love, he protests by urging her to “Call it not love, since love to heaven is fled, / Since sweating lust on earth usurped the name.” It is just one of the many aphorisms from the poem that Robert Allott, the book’s editor, excerpts. But that is not quite how the passage goes in England’s Parnassus. “—Love to heaven is fled,” it reads, “Since sweating lust on earth usurpt the name.” As a heavy dash effaces the metalanguage that begins Adonis’s pronouncement, England’s Parnassus offers an early modern example of the transcultural tendency, documented by Greg Urban, for transcriptions to delete the metalanguage that marks them as transcribable in the first place, “as if the metadiscursive portions of the discourse were invisible (or inaudible) and yet capable of exercising an effect.” MATTHEW HUNTER

MATTHEW HUNTER In 2011, artist Khvay Samnang offered “piggyback” rides to residents and visitors of the White Building in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, as part of his performance piece, Samnang Cow Taxi. Titled colloquially with his given name, it was a humble undertaking. Khvay wore handmade cow horns (fig. 1) and, despite his svelte frame, humorously carried people on his back as if he were a robust workhorse. Evoking the water buffalo, a laboring animal crucial to Cambodian agricultural practices, seemed an odd choice for someone ferrying people around the more urban setting of the White Building. Moreover, the taxi ride seemed to grant a touristic gaze for nonresidents of the dilapidated public housing complex. Yet the physical intimacy of the gesture, as well as the slowness and toil of it, lent a critical edge to the playful jaunt around the famous white apartment structure, transformed into a muddy gray from decades of neglect. The White Building was erected in 1963 as a modernist, utopian experiment in public housing. It was created soon after Cambodia’s independence in 1953 as part of a socially optimistic, homegrown wave of New Khmer Architecture, and it was intended to house civil servants and municipal workers. After the devastating Khmer Rouge regime collapsed in 1979, many returned to the city in need of housing, and the modest apartments were repopulated with dancers, musicians, artists, and filmmakers. Khvay’s own practice has been deeply indebted to the site and people of the White Building, and his slow, caring, arduous gesture highlighted a community of residents who, like the building itself, have been historically subject to state neglect, inattention, and habitual violence.

In 2011, artist Khvay Samnang offered “piggyback” rides to residents and visitors of the White Building in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, as part of his performance piece, Samnang Cow Taxi. Titled colloquially with his given name, it was a humble undertaking. Khvay wore handmade cow horns (fig. 1) and, despite his svelte frame, humorously carried people on his back as if he were a robust workhorse. Evoking the water buffalo, a laboring animal crucial to Cambodian agricultural practices, seemed an odd choice for someone ferrying people around the more urban setting of the White Building. Moreover, the taxi ride seemed to grant a touristic gaze for nonresidents of the dilapidated public housing complex. Yet the physical intimacy of the gesture, as well as the slowness and toil of it, lent a critical edge to the playful jaunt around the famous white apartment structure, transformed into a muddy gray from decades of neglect. The White Building was erected in 1963 as a modernist, utopian experiment in public housing. It was created soon after Cambodia’s independence in 1953 as part of a socially optimistic, homegrown wave of New Khmer Architecture, and it was intended to house civil servants and municipal workers. After the devastating Khmer Rouge regime collapsed in 1979, many returned to the city in need of housing, and the modest apartments were repopulated with dancers, musicians, artists, and filmmakers. Khvay’s own practice has been deeply indebted to the site and people of the White Building, and his slow, caring, arduous gesture highlighted a community of residents who, like the building itself, have been historically subject to state neglect, inattention, and habitual violence.