Available free of charge for a limited time

by Eleanor Craig, Amy Hollywood, and Kris Trujillo

In the introduction to this special issue, three of the co-editors explain that their goal “is to desegregate religious studies and theology from the humanities more broadly by reasserting religion’s significance to the histories of critique, theory, and literature … [and to] pursue connections between devotional practices, literary production, and contemplative or intellectual labor so as to move the intellectual project called Religion and Literature away from an emphasis on thematics and toward an investigation of practices.”

In the introduction to this special issue, three of the co-editors explain that their goal “is to desegregate religious studies and theology from the humanities more broadly by reasserting religion’s significance to the histories of critique, theory, and literature … [and to] pursue connections between devotional practices, literary production, and contemplative or intellectual labor so as to move the intellectual project called Religion and Literature away from an emphasis on thematics and toward an investigation of practices.”

The introduction begins:

Is there a place for devotion in criticism? What about love and desire? Recent attempts to historicize and parochialize critique as one method of interpretation among others lead to these questions. Deidre Lynch’s Loving Literature: A Cultural History (2015) identifies love as a requirement for critique and turns “to histories of criticism, canonicity, literary history, and ‘heritage,’ and, above all, to the emergence . . . of new etiquettes of literary appreciation . . . so as to examine how it has come to be that those of us for whom English is a line of work are also called upon to love literature and to ensure that others do so too.” Rita Felski offers a different analysis of the field in The Limits of Critique (2015), positing and resisting as central to literary study a version of critique to which love is antithetical—that is, a critique that “highlights the sphere of the agon (conflict and domination) at the expense of eros (love and connection) [and assumes] that the former is more fundamental than the latter.” Despite their distinct formulations of the relationship between love and critique and the role each plays within literary studies past and present, Lynch and Felski both argue that love ought to be central to the discipline.

This newfound interest in love, desire, and affect echoes, in many ways, to the call voiced a decade and a half ago in the edited volume Polemic: Critical or Uncritical (2004). There Jane Gallop, Michael Warner, and others ask that literary scholars think with and about practices of “uncritical” reading and author love in order to understand the modes of subject formation to which these reading practices are bound. The “uncritical” reader, in particular the one who identifies too closely with characters, who invests too deeply in a plot, or who becomes a card-carrying member of an author’s fan club, remains a serious object of study, especially in light of theoretical developments in affect theory, digital humanities, and fan studies. Yet a slightly different argument also appears in the volume. This is the claim that religious readers, like Lynch’s literature loving readers, can be and in fact often are also critical readers. Michael Warner’s pious readers and Amy Hollywood’s mystical subjects have been joined in recent years by Mark Jordan’s convulsing bodies, Aisha Beliso-De Jesús’s electric “copresences,” and Ashon Crawley’s stomping spirits. Yet despite the foundational role that religion plays in twenty-first century conversations about the history and value of critique, these religious figures seem largely to have disappeared from literary critical discussions of the issue.[v] Why are religious readers, particularly markedly embodied religious readers, absent from recent histories of literary criticism? Have they been forced to remain uncritical, scapegoats whose erasure enables other modes of putatively “uncritical” reading to be reclaimed as less excessive, credulous, or nonrational? Does postcriticism require a disavowal of the critical religious subject? These questions carry particular political relevance today, as the need for critical reading is ever more pressing and, simultaneously, the dangers of paranoia as the presumptive critical stance have become all too clear.

The essays collected here return to the questions raised in earlier scholarship about the interplay of love and the literary-critical enterprise by attending to the practices of devotion. Following Richard Rambuss’s claim that devotional texts “afford us a plethora of affectively charged sites for tracing the complex overlappings and relays between religious devotion and erotic desire, as well as between the interiorized operations of the spirit and the material conditions of the body,” the essays gathered here demonstrate the close relationship between literary reading, critical reading, and devotion. Attending to the intersections of devotional practices (among them, prayer, recitation, scriptural exegesis, meditation, and contemplation) and the rhetorical and literary arts (invention, poetry, and fiction), contributors explore the ways in which the reading, writing, and contemplative practices of Christianity contribute—both historically and in the present—to the training, cultivation, and disciplining of affective attachments to, investments in, and analyses of literature. Contributors also examine the relationship between religious devotion and the devotion to literature through analyses of the ways in which materiality and embodiment condition the connections between devotional practices and the textual arts.

The goal of this special issue, then, is to desegregate religious studies and theology from the humanities more broadly by reasserting religion’s significance to the histories of critique, theory, and literature. Most of the authors are scholars of religion, and we all work with the assumption that the putative secularity of literary study in English is largely a ruse. Rather, religious frameworks, sensibilities, and practices have been present in the study of English literature from the beginning, even at the moments when the literary was most strenuously attempting to differentiate itself from the religious. This is not only a more accurate account of contemporary critical frameworks and their evolution, but a signal of their limitations. Practices identified as the sole domain of a largely secular form of literary expertise may be more parochially Christian than their practitioners realize. Generalized understandings of literary devotion developed within these frameworks might inadvertently limit what is considered critical or rigorous, even literary.

We use the term “devotion” in its broadest sense in order to question and undo the epistemological restrictions generated by sharp distinctions between the secular and the religious. These essays pursue connections between devotional practices, literary production, and contemplative or intellectual labor so as to turn the intellectual project called Religion and Literature away from an emphasis on thematics and toward an investigation of practices. We follow Niklaus Largier’s proposal that those writing the history of Christian mysticism and secular modernity move away from identifying persistent motifs and intellectual paradigms shared by medieval mystics and modern intellectuals and, instead, toward an interrogation of the ways that practices of reading shape sensation, perception, and what he calls “a poetics or poiesis of experience.” We ask not only how religious practices are organized around literature but also how these practices are transmuted into putatively secular forms of devotion. How might one be “religiously devoted,” for example, in a political (devotion to candidate, cause, state), epistemological (devotion to methods and objects of disciplinary formation), or aesthetic (devotion to artistic pursuits, modes of experimentation, or artifacts of popular culture) sense? To what extent can we demarcate religious and nonreligious devotion, and what is at stake in attempts to do so?

Most importantly, perhaps, these essays demonstrate that the work of devotion is as much about the transformation wrought through it as it is about the specificity of its object. Moreover, as these essays show, this emphasis on transformation was already in place in the Christian Middle Ages. We collectively are interested in devotion not as a stance of subservience before a divine or human other, but as transformative practice. Devotion does not merely—or uncritically—receive, follow, and reinscribe predetermined patterns of thought or courses of action. The ends or outcomes of its critical performances are not fully known in advance, even when they are animated by identifiable desires. The essays in this issue thus read for textual accounts of devotional practices as well as the ways in which the text itself delivers or demands particular forms of practice. Read the full introduction free of charge …

ELEANOR CRAIG is Program Director and Lecturer for the Committee on Ethnicity, Migration, Rights at Harvard University.

AMY HOLLYWOOD is the Elizabeth H. Monrad Professor of Christian Studies at Harvard Divinity School and a member of the Committee for the Study of Religion at Harvard University.

KRIS TRUJILLO is Assistant Professor in the Department of Comparative Literature at the University of Chicago.

This essay considers an instance of medieval fictionality through the devotional text The Life of the Servant by the Dominican Henry Suso, specifically, through an examination of the “Servant’s” attempt to identify with Christ. Two forms of doubleness issue from this attempt, namely, the human servant seeking to embody the divine without remainder and his figuration as sinner and savior. Insofar as the text allows for a play between these polarities, the servant’s devotional practice can be understood as inhabiting the “as if,” or a kind of fictionality. The temptations of a devotional literalism—fiction striving to overcome its fictionality—is portrayed in the Life alongside a vision of devotion that retains the suspensions and play of the fictional.

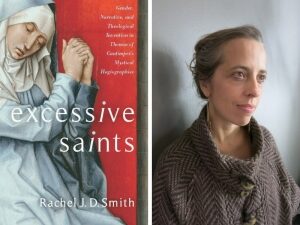

This essay considers an instance of medieval fictionality through the devotional text The Life of the Servant by the Dominican Henry Suso, specifically, through an examination of the “Servant’s” attempt to identify with Christ. Two forms of doubleness issue from this attempt, namely, the human servant seeking to embody the divine without remainder and his figuration as sinner and savior. Insofar as the text allows for a play between these polarities, the servant’s devotional practice can be understood as inhabiting the “as if,” or a kind of fictionality. The temptations of a devotional literalism—fiction striving to overcome its fictionality—is portrayed in the Life alongside a vision of devotion that retains the suspensions and play of the fictional. RACHEL SMITH

RACHEL SMITH In the introduction to this special issue, three of the co-editors explain that their goal “is to desegregate religious studies and theology from the humanities more broadly by reasserting religion’s significance to the histories of critique, theory, and literature … [and to] pursue connections between devotional practices, literary production, and contemplative or intellectual labor so as to move the intellectual project called Religion and Literature away from an emphasis on thematics and toward an investigation of practices.”

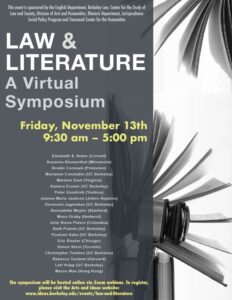

In the introduction to this special issue, three of the co-editors explain that their goal “is to desegregate religious studies and theology from the humanities more broadly by reasserting religion’s significance to the histories of critique, theory, and literature … [and to] pursue connections between devotional practices, literary production, and contemplative or intellectual labor so as to move the intellectual project called Religion and Literature away from an emphasis on thematics and toward an investigation of practices.”  UC Berkeley’s Townsend Center for the Humanities presents an event featuring Representations board members

UC Berkeley’s Townsend Center for the Humanities presents an event featuring Representations board members