Bob Dylan in the Country: Rock Domesticity and Pastoral Song

by Timothy Hampton

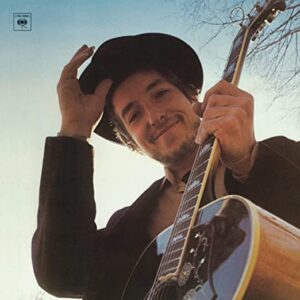

At the close of the 1960s two developments changed the shape of mainstream rock and roll music. The first was a new focus, on the part of a number of influential artists, on music about domestic life—kids, spouses, home. The second was a new interest in blending rock rhythms with instrumentation and themes taken from country music. This essay explores the ways in which these two concerns overlap in the work of Bob Dylan. I argue that Dylan’s work at the turn of the decade offers insights into our own current moment, when the relationship between the public world and the private world is being renegotiated. I show how Dylan’s “country” songs are, in fact, models of self-conscious experimentation that push against the conventions of popular song and highlight the conditions of their own production.

At the close of the 1960s two developments changed the shape of mainstream rock and roll music. The first was a new focus, on the part of a number of influential artists, on music about domestic life—kids, spouses, home. The second was a new interest in blending rock rhythms with instrumentation and themes taken from country music. This essay explores the ways in which these two concerns overlap in the work of Bob Dylan. I argue that Dylan’s work at the turn of the decade offers insights into our own current moment, when the relationship between the public world and the private world is being renegotiated. I show how Dylan’s “country” songs are, in fact, models of self-conscious experimentation that push against the conventions of popular song and highlight the conditions of their own production.

The essay begins:

One day, around 1970, John Lennon took a bath. Then he wrote a song about it. “In the middle of a bath I call your name,” sang the composer of “Revolution.” Next, he shared his call with his wife: “Oh, Yoko! Your love will turn me on.” About the same time, Lennon’s erstwhile writing partner, Paul McCartney, went to his second home in rural Scotland to get away from the press. There, the composer of “Eleanor Rigby” got down to work: “Fly flies in, fly flies out,” he sang on his second solo album, Ram. While McCartney was in Scotland, the American writer Paul Simon went to his doctor for a checkup. His song “Bridge Over Troubled Water” had recently stood with McCartney’s “Let It Be” as an anthem of consolation for a generation exhausted by war and political violence. Both tunes had achieved broad success with both white and black audiences—in the latter case, through covers by the soul singer Aretha Franklin. Simon’s GP read him the riot act about his fast living. Simon passed the news on to his spouse: “Peg, you better look around! How long you think you can run that body down?”

What is this stuff? By the end of the 1960s, rock and roll music had generated a canon of powerful songs built around a set of frequently reworked themes: sexual desire, regret, more sexual desire, rebellion, drugs, despair, escape, sexual desire. Now, all of a sudden, major composers in the field were writing about trivia.

The turn to domestic themes on the part of major white rock stars reflects the changing relationship between public art and personal expression at the end of the 1960s. Rock music’s extraordinarily rapid rise to dominance in the field of entertainment was built on images of rebellion and fictions of expanded consciousness. Now it seemed to have run out of steam. In part, it had been overwhelmed by the explosion of spectacle and drama that had taken over much political and social life. In the United States, the violence and confusion that followed the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King and the Democratic Convention in Chicago dwarfed expressions of youthful rebellion on the part of rich rock musicians. So these artists increasingly showcased themselves, not as rebels or teen-magazine “stars,” but as personalities. Songs about family life, bathing experiences, and dietary regimens began to creep into the canon, and listeners were turned into paparazzi in spite of themselves. The music seemed to be at a crossroads.

The moment has resonance. We now enter our own new “decade” (that conventional unit of pop culture history), and face a set of challenges that have rearranged our relationship to the public world, to private space, and to our understanding of community. The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has imposed a new experience of domestic space, as millions of people are compelled to shelter in place and wait for signs of improvement. Daily rituals of bathing (Lennon), home life (McCartney), and self-medication (Simon) replace the public experiences of political gathering (say, “Revolution”), face-to-face conversation (“Hey, Jude”), and street life (“The Sound of Silence”). In our own moment of nesting, not communing is both the prudent and the ethically correct thing to do. And yet, as the massive protests against racial injustice that erupted in May 2020 have also shown, the domestic idyll of self-quarantine is shaped by race and class. Sheltering in place is largely the prerogative of a professional class that remains overwhelmingly white, even as the protests against a segregated society have been strikingly multiracial. All of these factors raise the question of what we can learn from an earlier moment of political upheaval, and from the escapist art that was produced in response to it. Continue reading …

TIMOTHY HAMPTON is Professor of Comparative Literature and French at the University of California at Berkeley. His book, Bob Dylan: How the Songs Work, appeared in paperback in fall 2020. A new study, The Secret History of Cheerfulness: Shakespeare to Facebook, is forthcoming from Zone Books in 2021. He writes about literature, music, and education at www.timothyhampton.org.