by Jeffrey Knapp

The essay begins:

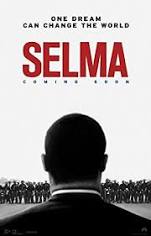

“This isn’t right.” Almost as soon as the man resembling Martin Luther King Jr. has begun to speak, he interrupts himself in frustration. “I accept this honor,” he’d been saying, “for our lost ones, whose deaths pave our path, and for the twenty million Negro men and women motivated by dignity and a disdain for hopelessness.” What does he think isn’t right? Is it the racial oppression he has been evoking? Or is it the felt inadequacy of his words to that injustice? As the man turns away from us, we find that he has been speaking into a mirror, and that he is frustrated in the immediate context by his efforts at getting dressed . “Corrie”—it is King, we now understand, and he’s not alone; his wife Coretta is with him—“this ain’t right.” “What’s that?” she asks, entering from another room. “This necktie. It’s not right.” “It’s not a necktie,” she corrects him, “it’s an ascot.” “Yeah, but generally, the same principles should apply, shouldn’t they? It’s not right.”

“This isn’t right.” Almost as soon as the man resembling Martin Luther King Jr. has begun to speak, he interrupts himself in frustration. “I accept this honor,” he’d been saying, “for our lost ones, whose deaths pave our path, and for the twenty million Negro men and women motivated by dignity and a disdain for hopelessness.” What does he think isn’t right? Is it the racial oppression he has been evoking? Or is it the felt inadequacy of his words to that injustice? As the man turns away from us, we find that he has been speaking into a mirror, and that he is frustrated in the immediate context by his efforts at getting dressed . “Corrie”—it is King, we now understand, and he’s not alone; his wife Coretta is with him—“this ain’t right.” “What’s that?” she asks, entering from another room. “This necktie. It’s not right.” “It’s not a necktie,” she corrects him, “it’s an ascot.” “Yeah, but generally, the same principles should apply, shouldn’t they? It’s not right.”

This opening to Selma announces the complexity not only of the movie itself but also of the genre to which it belongs—the historical film. First, there is the tonal instability of the scene, which swerves from the tragedy of “our lost ones” to the comedy of the ascot. Then there is the rhetorical switch from King’s earnest and formal speech to the colloquialism of his “ain’t” and the domestic ease of his “Corrie.” As the film reviewer Michael Sragow comments, these transformations seem intended “to signal to audiences that we’re in for an intimate, maybe irreverent look” at King; in general, A. O. Scott argues, Selma is dedicated to “restoring” King’s “human dimensions.” But the start of Selma also briefly confuses us about the meaning of a word that one might have assumed was the last one the movie would want us to feel confused about: “right,” as in “the right to vote,” “the right to assemble, and demonstrate,” “equal rights,” “civil rights.” “I don’t like how this looks,” King says of his ascot: what’s troubling him seems to be an aesthetic, not a moral offense. Another change in emphasis apparently neutralizes that distinction. When Coretta replies that the ascot “looks distinguished and debonair to me,” King clarifies that his objection has all along had a moral dimension to it. “You know what I mean,” he says to his wife: the ascot makes it seem “like we’re living high on the hog dressed like this, while folks back home are . . . It’s not right.” Just as King wants the language of his speech to match the weightiness of its subject, so he’s concerned that his clothes reflect his social commitments; in aesthetics as in ethics, he believes, “the same principles should apply.” Yet the disorienting shifts of focus in this first scene nevertheless emphasize the potential for principles to become misaligned. Something else “isn’t right” at the start of Selma: the man who speaks these words, the British actor David Oyelowo, is after all merely pretending to be Martin Luther King Jr., and for a moment we might think that he’s expressing nothing more than his dissatisfaction with his performance. The opening to Selma seems, in other words, to anticipate two sorts of skeptical responses to the film: first, that Selma falls short as a historical recreation, and second, that it does so because of its trivializing overinvestment in such merely aesthetic questions as how the recreation “looks.”

These are indeed the very charges that have been leveled against the film, although they have centered less on the portrayal of King than on the representation of another historical figure in the movie, Lyndon Johnson. In an editorial for the Washington Post, the former Johnson aide Joseph Califano Jr. argued that

the makers of the new movie Selma apparently just couldn’t resist taking dramatic, trumped-up license with a true story that didn’t need any embellishment to work as a big-screen historical drama. As a result, the film falsely portrays President Lyndon B. Johnson as being at odds with Martin Luther King Jr. and even using the FBI to discredit him, as only reluctantly behind the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and as opposed to the Selma march itself.

In Selma, Califano charged, aesthetics “trumped” ethics: the producers, screenwriter, and director felt “free to fill the screen with falsehoods, immune from any responsibility to the dead, just because they thought it made for a better story.” Even reviewers more sympathetic to the film have agreed with Califano about its misrepresentation of LBJ. Though praising Selma as “the best depiction of the civil rights struggle of the 1960s,” Albert R. Hunt nevertheless added that “it needlessly, and erroneously, casts Johnson as a reluctant supporter of the Voting Rights Act”; so, too, Ari Berman characterized the film’s account of Johnson as “unnecessarily one-sided.” What troubled all three critics was how “needlessly,” in their view, the makers of Selma had set their aesthetic desire for dramatic “embellishment” against a moral “obligation” to “the facts.”

Proponents of Selma have by and large declined to defend the historical accuracy of Johnson’s portrayal in the film, instead choosing to criticize the very demand for accuracy as hopelessly naive. “Did ‘Selma’ cut some corners and perhaps tilt characters to suit the needs of the story?” David Carr asked. “Why yes—just like almost every other Hollywood biopic and historical film that has been made.” Differentiating Selma from “a documentary or even a dramatized history,” Jamelle Bouie defined it as “a film based on historical accounts, and like all films of its genre, it has a loose relationship to actual history.” Consequently, Bouie added, “it’s better to look at deviations from established history or known facts” in Selma not as defects but rather “as creative choices—license in pursuit of art.” “I’m not a historian. I’m not a documentarian,” Selma’s director Ava DuVernay similarly maintained in a televised interview with Gwen Ifill: “This is art. This is a movie. This is a film.” According to the reviewer Bilge Ebiri, the only relevant terms for judging the rightness of historical films are aesthetic ones: “These movies are not documentaries, nor are they acts of journalism. . . . They’re narrative works, and just like any other narrative work, they need to be true to themselves.”

“Every year,” the film scholar Jeanine Basinger wearily complained when asked to comment on Selma, “I know someone is going to call me about distortion of history when we hit the Oscars.” But there’s a reason that the objection keeps recurring. If it’s a mistake to look for accuracy in historical films, then why do historical films bother with accuracy at all? Although DuVernay rejected the label of documentarian in her interview with Ifill, that is exactly how she began her directorial career, with the hip-hop documentary This Is the Life (2008)—and her next project after Selma was a documentary on the US criminal justice system, 13th. What’s more, historical verisimilitude mattered enough to DuVernay in making Selma that she meticulously reproduced the look and feel of the sixties in her film, chose actors who bore an uncanny physical resemblance to the figures they played, and even spliced actual documentary footage of the final march to Montgomery into Selma’s recreation of it. In the same interview where she claimed that she was no more of a historian than a documentarian, DuVernay expressed her dismay at the “jaw-dropping” ignorance of moviegoers regarding the events her film “chronicled,” and she hoped that her movie would help Selma “resonate with people in the way that it should as being just such a cornerstone of democracy.” Prominent participants in the march have indeed championed the film as historiography. “Everything” except the film’s “depiction of the interaction between King and Johnson,” Andrew Young has said, “they got 100 percent right.” But then how could historical accuracy not be an issue for a film that ends with King’s proclaiming, “His truth is marching on”? The tensions between fact and fiction in Selma are anything but incidental to the movie: they instead reflect the irreducibly hybrid nature of the historical film.

Is it possible to argue that a mix of fact and fiction is necessary to Selma and to historical films generally? Continue reading …

Every historical film must contend with the possibility that its viewers will be scandalized by its mixture of fact and fiction, but no recent historical film has faced such pressure to justify its hybrid nature as Selma has, in large part because no recent film has taken on so momentous and controversial a historical subject: the civil rights marches from Selma to Montgomery that led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. The renewed urgency of the issues Selma dramatizes, along with the film’s own commitment to the “moral certainty” of the civil rights movement, helps explain why Selma wavers in a self-defense that links the fictionality of its historical reenactments to the purposely theatrical element of the marches themselves. But politics are not the only problem for fiction in Selma, and to show why, this essay compares Selma to an earlier historical film, The Westerner (1940), that openly flaunts the commercial nature of its fictionality.

JEFFREY KNAPP is the Eggers Professor of English at the University of California, Berkeley, and a Faculty Affiliate of Berkeley’s Film and Media Department. He is most recently the author of Pleasing Everyone: Mass Entertainment in Renaissance London and Golden-Age Hollywood, published in 2017 by Oxford University Press.

David Henkin is Professor of History at UC Berkeley and a member of the Representations editorial board. His essay “Hebdomadal Form: Diaries, News, and the Shape of the Modern Week” was published in Representations 131.

David Henkin is Professor of History at UC Berkeley and a member of the Representations editorial board. His essay “Hebdomadal Form: Diaries, News, and the Shape of the Modern Week” was published in Representations 131. Waldo E. Martin is Professor of History at UC Berkeley.

Waldo E. Martin is Professor of History at UC Berkeley. Ronit Stahl is Assistant Professor of History Department at UC Berkeley.

Ronit Stahl is Assistant Professor of History Department at UC Berkeley.

In

In  “This isn’t right.” Almost as soon as the man resembling Martin Luther King Jr. has begun to speak, he interrupts himself in frustration. “I accept this honor,” he’d been saying, “for our lost ones, whose deaths pave our path, and for the twenty million Negro men and women motivated by dignity and a disdain for hopelessness.” What does he think isn’t right? Is it the racial oppression he has been evoking? Or is it the felt inadequacy of his words to that injustice? As the man turns away from us, we find that he has been speaking into a mirror, and that he is frustrated in the immediate context by his efforts at getting dressed . “Corrie”—it is King, we now understand, and he’s not alone; his wife Coretta is with him—“this ain’t right.” “What’s that?” she asks, entering from another room. “This necktie. It’s not right.” “It’s not a necktie,” she corrects him, “it’s an ascot.” “Yeah, but generally, the same principles should apply, shouldn’t they? It’s not right.”

“This isn’t right.” Almost as soon as the man resembling Martin Luther King Jr. has begun to speak, he interrupts himself in frustration. “I accept this honor,” he’d been saying, “for our lost ones, whose deaths pave our path, and for the twenty million Negro men and women motivated by dignity and a disdain for hopelessness.” What does he think isn’t right? Is it the racial oppression he has been evoking? Or is it the felt inadequacy of his words to that injustice? As the man turns away from us, we find that he has been speaking into a mirror, and that he is frustrated in the immediate context by his efforts at getting dressed . “Corrie”—it is King, we now understand, and he’s not alone; his wife Coretta is with him—“this ain’t right.” “What’s that?” she asks, entering from another room. “This necktie. It’s not right.” “It’s not a necktie,” she corrects him, “it’s an ascot.” “Yeah, but generally, the same principles should apply, shouldn’t they? It’s not right.” Hear Pulitzer Prize-Winning Writer HILTON ALS

Hear Pulitzer Prize-Winning Writer HILTON ALS