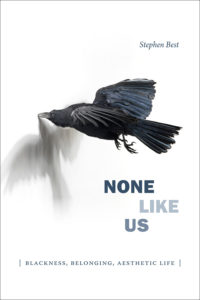

Stephen Best, UC Berkeley Professor, will be discussing his recent book:

None Like Us: Blackness, Belonging, Aesthetic Life

It passes for an unassailable truth that the slave past provides an explanatory prism for understanding the black political present. In None Like Us Stephen Best reappraises what he calls “melancholy historicism”—a kind of crime scene investigation in which the forensic imagination is directed toward the recovery of a “we” at the point of “our” violent origin. Best argues that there is and can be no “we” following from such a time and place, that black identity is constituted in and through negation, taking inspiration from David Walker’s prayer that “none like us may ever live again until time shall be no more.” Best draws out the connections between a sense of impossible black sociality and strains of negativity that have operated under the sign of queer. In None Like Us the art of El Anatsui and Mark Bradford, the literature of Toni Morrison and Gwendolyn Brooks, even rumors in the archive, evidence an apocalyptic aesthetics, or self-eclipse, which opens the circuits between past and present and thus charts a queer future for black study.

It passes for an unassailable truth that the slave past provides an explanatory prism for understanding the black political present. In None Like Us Stephen Best reappraises what he calls “melancholy historicism”—a kind of crime scene investigation in which the forensic imagination is directed toward the recovery of a “we” at the point of “our” violent origin. Best argues that there is and can be no “we” following from such a time and place, that black identity is constituted in and through negation, taking inspiration from David Walker’s prayer that “none like us may ever live again until time shall be no more.” Best draws out the connections between a sense of impossible black sociality and strains of negativity that have operated under the sign of queer. In None Like Us the art of El Anatsui and Mark Bradford, the literature of Toni Morrison and Gwendolyn Brooks, even rumors in the archive, evidence an apocalyptic aesthetics, or self-eclipse, which opens the circuits between past and present and thus charts a queer future for black study.

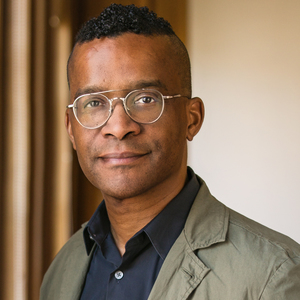

Stephen Best is Associate Professor of English at UC Berkeley. His research pursuits in the fields of American and African American criticism have been closely aligned with a broader interrogation of recent literary critical practice. Specifically, his interest in the critical nexus between slavery and historiography, in the varying scholarly and political preoccupations with establishing the authority of the slave past in black life, quadrates with his exploration of where the limits of historicism as a mode of literary study may lay, especially where that search manifests as an interest in alternatives to suspicious reading in the text-based disciplines.

Stephen Best is Associate Professor of English at UC Berkeley. His research pursuits in the fields of American and African American criticism have been closely aligned with a broader interrogation of recent literary critical practice. Specifically, his interest in the critical nexus between slavery and historiography, in the varying scholarly and political preoccupations with establishing the authority of the slave past in black life, quadrates with his exploration of where the limits of historicism as a mode of literary study may lay, especially where that search manifests as an interest in alternatives to suspicious reading in the text-based disciplines.

He has edited a number of special issues of Representations: “Redress” (with Saidiya Hartman), on theoretical and political projects to undo the slave past; “The Way We Read Now” (with Sharon Marcus), on the limits of symptomatic reading; and “Description Across Disciplines” (with Sharon Marcus and Heather Love), on disciplinary valuations of description as critical practice. In addition to None Like Us, he is the author of The Fugitive’s Properties: Law and the Poetics of Possession.

Michael Lucey

Michael Lucey

This lecture is drawn from Rey Chow’s chapter in the anthology

This lecture is drawn from Rey Chow’s chapter in the anthology  In

In