Skeletal Classicism: Zoological Osteology and Art-Historical Method in Early Twentieth-Century France

by Todd P. Olson

In this essay Todd Olson follows an art-historical method, from a formalist analysis of French Classicism derived from the natural sciences to the nineteenth-century biological discourse that identified hidden analogies rather than visual similarities among different specimens, whether they were animals or paintings. Olson shows how an ambivalence to the use of biological metaphors in North American art history may be traced back to this theoretical genealogy.

The essay begins:

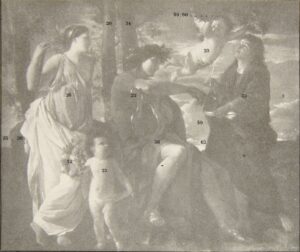

A constellation of numerals is superimposed on Nicolas Poussin’s L’Inspiration du poète. The numbers 35, 20, 26, 12, 23, 34, 22, 36, 59, 60, 62, 33, 9, and 3 are scattered across the surface of the canvas. The numbers may indicate a caption, or, more likely, since the numbers range from 3 to at least 62, they refer to an index. One may also infer that the numbers correspond to motifs in an attempt to provide an iconographic catalog. Yet, the repetition of 20, 23, and 59 reveals a lack of correspondence between number and depicted object. Although 23 refers to the flesh of two putti, 20 marks both rock and tree trunk; 59 indexes two patches of sky.

The transparent paper overlay with the numeric system on the photographic reproduction is one of several in Otto Grautoff’s Nicolas Poussin (1914), a major catalog of the French seventeenth-century painter’s oeuvre. Paintings were numerically compared to one another. Poussin’s L’Inspiration du poète was linked to Les Bergers d’Arcadie: the shoulder of the woman among shepherds and the garland-bearing putto’s skin, the tomb and the patch of rock. The cloth falling over the knee of Apollo and a bacchante’s drapery in the London Triumph of Pan share the number 36; aside from “36,” L’Inspiration du poète and a bacchanal have nothing in common.

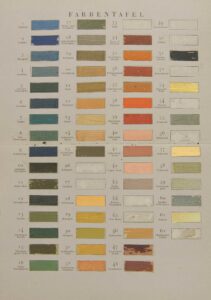

The clue to the pattern of numbers cross-referencing the fields in individual paintings with other pictures by Poussin is offered by a chart (Farbentafel) in the back of the book, where sixty-two brushstrokes of oil paint were applied to sixty-two printed rectangles. Grautoff made it possible to analyze Poussin’s palette through systematic chromatic separation, numerical hue assignment, and graphic indexing.

The clue to the pattern of numbers cross-referencing the fields in individual paintings with other pictures by Poussin is offered by a chart (Farbentafel) in the back of the book, where sixty-two brushstrokes of oil paint were applied to sixty-two printed rectangles. Grautoff made it possible to analyze Poussin’s palette through systematic chromatic separation, numerical hue assignment, and graphic indexing.

Grautoff and his publishers were caught between the age of engraving and the era of color photography. In the first years of photographic reproduction, black-and-white prints may have sufficed for the analysis of iconography. Ten years after the publication of Grautoff’s book, Aby Warburg famously began creating a photographic archive to display the iconographic specimens in his Mnemosyne Atlas. Warburg traced motifs through time and across geographies, such as the Mithraic mystery cult’s “world-spanning range and force” from the Roman Empire to the Hopi kiva. By contrast, Grautoff’s numbers attend to the formal characteristics of a single painter. Nevertheless, the color analysis of Poussin’s paintings registered the patterns of a complex system. Things, regardless of their shape or function, were sorted out and made commensurate under another differential visual order. The painter’s palette entered a chromatic archive.

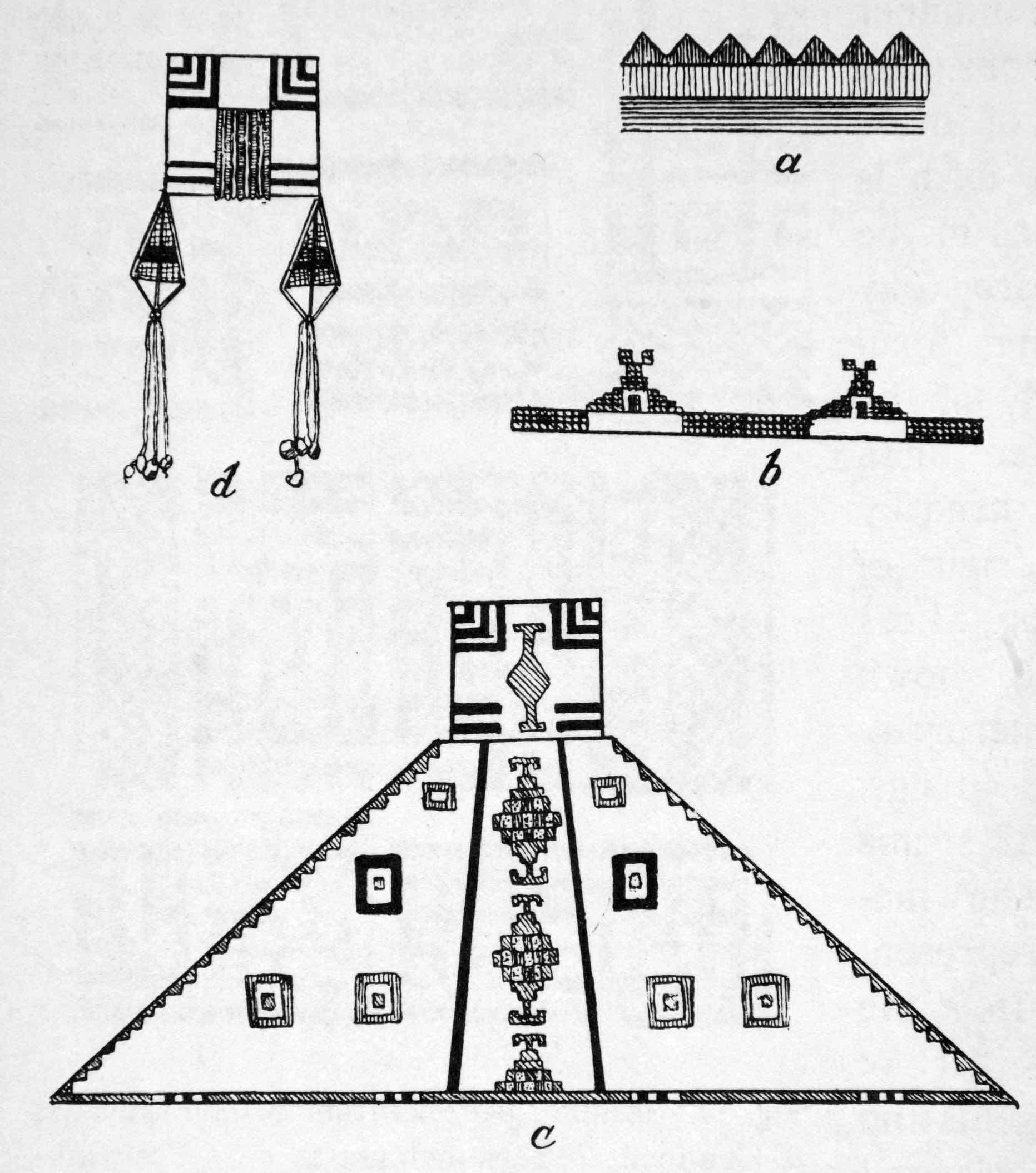

Grautoff provided the basis for scientific analysis without regard for iconography. The numerical register of colors reminds us of the diagrams used by the anthropologist John Layard in the 1930s to analyze the impersonal cultural patterns shared by Malakulan dance and graphic art. It would appear that by 1914 a similar rigorous formalism was already in place, which Grautoff was able use to organize the dispersed easel paintings of the seventeenth-century artist into a coherent oeuvre in the absence of documented provenance.

The study of the systematic distribution of color lent itself to the kinds of formal analysis found in the German art-historical tradition of Jacob Burckhardt and Heinrich Wölfflin. In Walter Friedländer’s contemporary folio edition Nicolas Poussin (1914) we find the most explicit association of Poussin with Classicism. Following his teacher Wölfflin, Friendländer established an opposition between the Classical and the Baroque in his analysis of Poussin’s painting. For Grautoff and Friedländer, culture is an impersonal operation.

The author was dead, yet, “Poussin” was hard to kill. Much of the appreciation of the artist in France followed from Honoré de Balzac’s short story Le Chef d’oeuvre inconnu, in which the character of the young Poussin sacrifices his lover, Gillette, in the service of art as Frenhofer’s model. The artist would continue throughout the nineteenth century to be the central organizing principle of the discipline of art history in France. Émile Magne’s Nicolas Poussin, for example, was published in the same year as Grautoff’s and Friedländer’s books. Magne drew on the recent publication of La Correspondance de Nicolas Poussin, edited by Ch. Jouanny, to construct a work of biographical criticism, which complemented his other major work on seventeenth-century French literature, Scarron et son milieu (1905). In this work, Magne sets the classical Poussin as a foil to Paul Scarron, the author of the burlesque Virgile travesti. Many have rushed to Poussin’s correspondence to underscore this opposition: “My nature compels me to seek and love things that are well ordered, fleeing confusion, which is as contrary and inimical to me as is day to the deepest night.”

Based on a reading of the major German publications of 1914, it would appear that Poussin was securely associated with the discourse of Classicism and a formalist account in art history. While Grautoff’s numerical system may now seem anachronistic, his formalist project premised on the dissociation of color from iconography would have a lasting effect. Similarly, Friedländer’s formalist approach to the problem of Classicism was influential in twentieth-century art-historical scholarship in the English language. Wölfflin’s binary of the Classical and the Baroque would hold sway over the association of Poussin with Klassizismus.. By contrast, Magne’s approach to archival research resonated with the study of l’art classique in France, but it did not offer a rigorous theoretical foundation for that scientific project. It would seem that the identification of Classical art with Poussin’s painting was deeply rooted in a formalist approach that based its model of transformation on German rather than French philosophical traditions.

Yet, if we look to the French publications surrounding the acquisition of L’Inspiration du poète by the Musée du Louvre in 1911, a different theoretical lineage of Poussin’s Classicism emerges. While Magne’s archival and biographical approach continued to have a lasting impact on scholarship in France, an important latent French formalist discourse independent of the German tradition was in an early stage of development. In the prewar period, French literary modernism and the natural sciences were aligned, offering a formalist discourse for the criticism of painting that was paradoxically ambivalent toward vision. Form was hidden. Continue reading …

TODD P. OLSON is Professor of Early Modern Art in the Department of History of Art at the University of California, Berkeley, and a member of the editorial board of Representations.. He is author of Poussin and France: Painting, Humanism and the Politics of Style (2002) and Caravaggio’s Pitiful Relics (2014). His current book project is Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652): Skin, Repetition, and Painting in Viceregal Naples.

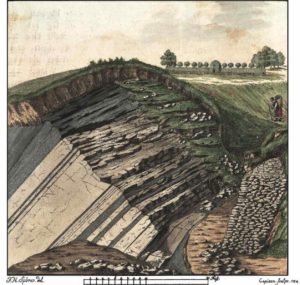

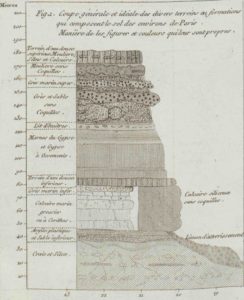

Decorative elements borrowed from topographical landscape drawing have been abandoned, and the human figure is excluded altogether. Instead, rock strata are organized along a vertical axis whose annotations reflect both their relative depth and the geological era in which they were thought to have formed. In late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century stratigraphic diagrams, geological history came into view for the first time, pictured as a function of depth.

Decorative elements borrowed from topographical landscape drawing have been abandoned, and the human figure is excluded altogether. Instead, rock strata are organized along a vertical axis whose annotations reflect both their relative depth and the geological era in which they were thought to have formed. In late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century stratigraphic diagrams, geological history came into view for the first time, pictured as a function of depth. Atop the rock, man. The German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich, known for his love of the Harz Mountains, pictured a strikingly different early nineteenth-century encounter between the human and the geological in his Wanderer Above a Sea of Clouds. From a granite outcropping, an eponymous wanderer placidly surveys the rocky mountain formations shrouded in mist below him and the faintly rendered peaks that flicker into view in the distance. The figure’s physical elevation over his environment and his panoramic view suggest the fantasy of a geological landscape visually possessed and perhaps also physically mastered by the human subject. Long used as a kind of art-historical shorthand for European Romanticism in general, the painting has more recently been taken as emblematic of a model of early nineteenth-century bourgeois subjectivity concomitant with the rise of modern spectatorial practices: “the ascendancy of newly realized bourgeois aspirations, fantasies of autonomy” that, Jonathan Crary writes, “permitted at least an optical appropriation” of the natural world, if not a literal one. Like Crary’s, a number of influential accounts of the painting grant interpretive priority to how the painting frames the role and status of the human figure qua a perceptual encounter with nature, whether mediated or direct.

Atop the rock, man. The German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich, known for his love of the Harz Mountains, pictured a strikingly different early nineteenth-century encounter between the human and the geological in his Wanderer Above a Sea of Clouds. From a granite outcropping, an eponymous wanderer placidly surveys the rocky mountain formations shrouded in mist below him and the faintly rendered peaks that flicker into view in the distance. The figure’s physical elevation over his environment and his panoramic view suggest the fantasy of a geological landscape visually possessed and perhaps also physically mastered by the human subject. Long used as a kind of art-historical shorthand for European Romanticism in general, the painting has more recently been taken as emblematic of a model of early nineteenth-century bourgeois subjectivity concomitant with the rise of modern spectatorial practices: “the ascendancy of newly realized bourgeois aspirations, fantasies of autonomy” that, Jonathan Crary writes, “permitted at least an optical appropriation” of the natural world, if not a literal one. Like Crary’s, a number of influential accounts of the painting grant interpretive priority to how the painting frames the role and status of the human figure qua a perceptual encounter with nature, whether mediated or direct. In 2011, artist Khvay Samnang offered “piggyback” rides to residents and visitors of the White Building in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, as part of his performance piece, Samnang Cow Taxi. Titled colloquially with his given name, it was a humble undertaking. Khvay wore handmade cow horns (fig. 1) and, despite his svelte frame, humorously carried people on his back as if he were a robust workhorse. Evoking the water buffalo, a laboring animal crucial to Cambodian agricultural practices, seemed an odd choice for someone ferrying people around the more urban setting of the White Building. Moreover, the taxi ride seemed to grant a touristic gaze for nonresidents of the dilapidated public housing complex. Yet the physical intimacy of the gesture, as well as the slowness and toil of it, lent a critical edge to the playful jaunt around the famous white apartment structure, transformed into a muddy gray from decades of neglect. The White Building was erected in 1963 as a modernist, utopian experiment in public housing. It was created soon after Cambodia’s independence in 1953 as part of a socially optimistic, homegrown wave of New Khmer Architecture, and it was intended to house civil servants and municipal workers. After the devastating Khmer Rouge regime collapsed in 1979, many returned to the city in need of housing, and the modest apartments were repopulated with dancers, musicians, artists, and filmmakers. Khvay’s own practice has been deeply indebted to the site and people of the White Building, and his slow, caring, arduous gesture highlighted a community of residents who, like the building itself, have been historically subject to state neglect, inattention, and habitual violence.

In 2011, artist Khvay Samnang offered “piggyback” rides to residents and visitors of the White Building in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, as part of his performance piece, Samnang Cow Taxi. Titled colloquially with his given name, it was a humble undertaking. Khvay wore handmade cow horns (fig. 1) and, despite his svelte frame, humorously carried people on his back as if he were a robust workhorse. Evoking the water buffalo, a laboring animal crucial to Cambodian agricultural practices, seemed an odd choice for someone ferrying people around the more urban setting of the White Building. Moreover, the taxi ride seemed to grant a touristic gaze for nonresidents of the dilapidated public housing complex. Yet the physical intimacy of the gesture, as well as the slowness and toil of it, lent a critical edge to the playful jaunt around the famous white apartment structure, transformed into a muddy gray from decades of neglect. The White Building was erected in 1963 as a modernist, utopian experiment in public housing. It was created soon after Cambodia’s independence in 1953 as part of a socially optimistic, homegrown wave of New Khmer Architecture, and it was intended to house civil servants and municipal workers. After the devastating Khmer Rouge regime collapsed in 1979, many returned to the city in need of housing, and the modest apartments were repopulated with dancers, musicians, artists, and filmmakers. Khvay’s own practice has been deeply indebted to the site and people of the White Building, and his slow, caring, arduous gesture highlighted a community of residents who, like the building itself, have been historically subject to state neglect, inattention, and habitual violence.

Trying to understand pain tolerances as a symptom of culture already gets us entangled in a second distinction: that between pain experiences and pain expressions. Here we enter upon a field of investigation in which the historian of art feels right at home, since questions surrounding the representation of pain in the visual arts have always been part and parcel of imitative art’s charge to represent psychic states and moral virtues—or their opposites—through coded bodily movements, gestures, and physiognomic signs. But questions of pathetic naturalism only get us so far in explaining why, for example, the famous clenched brow of the Trojan priest Laocoön in the eponymous figure group in Rome, as a physiognomic token of pain, communicated to its beholders a “pain-experience” so different from the one conveyed by its counterpart in the Master of Flémalle’s image of a Crucified Thief. We could rehearse the clichéd contrast between heroic death in pagan tragedy and sacrificial suffering in Christian theology to see that distinct narratives of human suffering and conflict are what drive the transferences between pain experiences, pain representations, and pain perceptions. Would we find that it is the very possibility of narrative that makes pain culturally intelligible in the first place? What’s clear is that the full implications of a culture’s narrative-ideological meanings for pain expression in the visual arts would be lost if we failed to attend to the situated functions of images, the peculiar agency they are granted to enlist the beholder’s effort in realizing their effects and completing their meanings in historically specific situations of use. Something of the logic of that agency can be recovered and measured by the forms of response demanded and structured by the image. We may begin, then, with one kind of image that, in portraying the very response it demands, tells us something about the peculiar way spectacular pain expressions registered in late medieval culture.

Trying to understand pain tolerances as a symptom of culture already gets us entangled in a second distinction: that between pain experiences and pain expressions. Here we enter upon a field of investigation in which the historian of art feels right at home, since questions surrounding the representation of pain in the visual arts have always been part and parcel of imitative art’s charge to represent psychic states and moral virtues—or their opposites—through coded bodily movements, gestures, and physiognomic signs. But questions of pathetic naturalism only get us so far in explaining why, for example, the famous clenched brow of the Trojan priest Laocoön in the eponymous figure group in Rome, as a physiognomic token of pain, communicated to its beholders a “pain-experience” so different from the one conveyed by its counterpart in the Master of Flémalle’s image of a Crucified Thief. We could rehearse the clichéd contrast between heroic death in pagan tragedy and sacrificial suffering in Christian theology to see that distinct narratives of human suffering and conflict are what drive the transferences between pain experiences, pain representations, and pain perceptions. Would we find that it is the very possibility of narrative that makes pain culturally intelligible in the first place? What’s clear is that the full implications of a culture’s narrative-ideological meanings for pain expression in the visual arts would be lost if we failed to attend to the situated functions of images, the peculiar agency they are granted to enlist the beholder’s effort in realizing their effects and completing their meanings in historically specific situations of use. Something of the logic of that agency can be recovered and measured by the forms of response demanded and structured by the image. We may begin, then, with one kind of image that, in portraying the very response it demands, tells us something about the peculiar way spectacular pain expressions registered in late medieval culture.

“The essays collected here counter [the] fantasy of pain as a knowable sensation that lies within that is then represented, or misrepresented, in language. Instead, they consider pain as always already enmeshed in social life, and representation as the means through which we can engage this imbrication. In so doing, they demonstrate the importance of bringing together two approaches to the problem of pain that have often been kept distinct. The first is the anthropological insight that pain behavior constitutes a mode of social engagement and, hence, that suffering is necessarily bound up with shifting, often unpredictable, cultural, familial, and interpersonal dynamics. The second involves a historical and literary-critical account of representation’s complex and productive relations to both experience and culture.” –from the editor’s introduction

“The essays collected here counter [the] fantasy of pain as a knowable sensation that lies within that is then represented, or misrepresented, in language. Instead, they consider pain as always already enmeshed in social life, and representation as the means through which we can engage this imbrication. In so doing, they demonstrate the importance of bringing together two approaches to the problem of pain that have often been kept distinct. The first is the anthropological insight that pain behavior constitutes a mode of social engagement and, hence, that suffering is necessarily bound up with shifting, often unpredictable, cultural, familial, and interpersonal dynamics. The second involves a historical and literary-critical account of representation’s complex and productive relations to both experience and culture.” –from the editor’s introduction

Representations 145

Representations 145

The prize jury praised the essay, calling it “highly innovative in its approach to the interpretation of a famously problematic episode in the career of Aleksandr Rodchenko: the work produced during his visit to the White Sea-Baltic Canal, one of the first Soviet forced labor camps, in the early 1930s.”

The prize jury praised the essay, calling it “highly innovative in its approach to the interpretation of a famously problematic episode in the career of Aleksandr Rodchenko: the work produced during his visit to the White Sea-Baltic Canal, one of the first Soviet forced labor camps, in the early 1930s.” Franz Boas (d. 1942) was born into an educated Jewish family in Westphalia in 1858; by 1888, at the age of thirty, he had settled permanently in the United States, in New York City. Today Boas is perhaps best known for his lifelong critiques of racialist theory and its concomitants in anti-Semitism and Nazism. He broadcast his arguments indefatigably from Columbia University (where he taught from 1899 until his death) into the public forum; one such statement was his memorable 1924 letter to the New York Times, “Lo, the Poor Nordic!,” in which he set out to refute Henry Fairfield Osborn (chief paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History), who was advocating the innate superiority of the “Nordic race.” By the 1920s, the German-Jewish immigrant Boas was writing with immense authority as one of the internationally recognized founders of American anthropology—that is, both of Americanist anthropology and of anthropology in North America (the United States and Canada; Boas did much of his fieldwork in the latter nation).

Franz Boas (d. 1942) was born into an educated Jewish family in Westphalia in 1858; by 1888, at the age of thirty, he had settled permanently in the United States, in New York City. Today Boas is perhaps best known for his lifelong critiques of racialist theory and its concomitants in anti-Semitism and Nazism. He broadcast his arguments indefatigably from Columbia University (where he taught from 1899 until his death) into the public forum; one such statement was his memorable 1924 letter to the New York Times, “Lo, the Poor Nordic!,” in which he set out to refute Henry Fairfield Osborn (chief paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History), who was advocating the innate superiority of the “Nordic race.” By the 1920s, the German-Jewish immigrant Boas was writing with immense authority as one of the internationally recognized founders of American anthropology—that is, both of Americanist anthropology and of anthropology in North America (the United States and Canada; Boas did much of his fieldwork in the latter nation). WHITNEY DAVIS

WHITNEY DAVIS