by Erica Weaver

The central regulatory document of the tenth-century English Benedictine Reform, Æthelwold of Winchester’s Regularis concordia, contains an important performance piece: the Visitatio sepulchri, which standard theater histories understand as an anomalous originary text that marks the reemergence of drama in the European Middle Ages. This article resituates it alongside the schoolroom colloquies of Æthelwold’s student Ælfric of Eynsham and his student and editor Ælfric Bata to argue that these texts together cultivated monastic self-possession by means of self-conscious performances of its absence. By staging (in)attention, they thereby modeled extended engagement in moments and spaces that could otherwise seem too quiet or empty to hold concentration for long, from the classroom to the sepulcher to the page, while also exposing the limits of “distraction” and “attention” as analytical terms.

The central regulatory document of the tenth-century English Benedictine Reform, Æthelwold of Winchester’s Regularis concordia, contains an important performance piece: the Visitatio sepulchri, which standard theater histories understand as an anomalous originary text that marks the reemergence of drama in the European Middle Ages. This article resituates it alongside the schoolroom colloquies of Æthelwold’s student Ælfric of Eynsham and his student and editor Ælfric Bata to argue that these texts together cultivated monastic self-possession by means of self-conscious performances of its absence. By staging (in)attention, they thereby modeled extended engagement in moments and spaces that could otherwise seem too quiet or empty to hold concentration for long, from the classroom to the sepulcher to the page, while also exposing the limits of “distraction” and “attention” as analytical terms.

The essay begins:

As a key component of the tenth-century correction movement that effectively created Benedictine monasticism, and in the process reshaped monastic life across Europe, Bishop Æthelwold of Winchester appointed a new kind of monastic figure for all of the familiae of England: that of the circa or roundsman, so called because the role required making rounds. First attested on the Continent in the eighth century and included in consuetudinaries (guides to the customs of particular monasteries) from across Francia and Lotharingia, the office had initially been conceived of as a means of policing sins of the tongue and ensuring silence, but it quickly became a deterrent to sexual misconduct and the temptations of sleep among other increasingly psychological threats to ascetic life. Æthelwold’s Regularis concordia (ca. 970), the central regulatory document that tailored the Rule of Saint Benedict for all English monks and nuns, sanctioned by King Edgar (r. 959–75) and ratified at the Synod of Winchester, dedicated one of its twelve chapters to the figure. Here, Æthelwold specifies that when the circa noticed aberrant behavior on his rounds, he silently swept by, but “in Chapter the next day” (in capitulo uenturi diei), he would publicly chastise wayward monks and nuns for their faults unless they immediately begged forgiveness “for some trifling offense” (pro leui qualibet culpa; 118.1381–82). The coercive surveillance was meant to feel absolute. As Ulrich of Zell (1029–93) enjoined a half-century after the office was introduced in England, “Let them patrol the whole monastery not just once but many times a day, so that there may be neither a place nor an hour in which any brother, if he should be up to anything, is able to be untroubled about being caught and shamed” (Totum claustrum non semel, sed multoties in die circumeant, ut nec locus sit nec hora in qua frater ullus securus esse possit, si tale quid commiserit, non deprehendi et non publicari).

Tenth-century reformers added a lantern to the circa’s arsenal, “so that in the night hours, when he ought to do so, he might position himself to look around” (qua nocturnis horis, quibus oportet hec agere, uidendo consideret; 119.1390–91). Thus equipped, the figure was meant to keep an especially close watch during matins, the long office occurring nightly between midnight and dawn, when he would patrol the ranks with his lantern in order to spotlight anyone who dozed instead of standing at attention. Æthelwold provides a vivid portrait:

And while the lections are being read at nocturns, during the third or fourth lection, just as it seems to be expedient, let him circulate through the choir; and, if he should discover a brother overwhelmed by sleep, he should place the lantern before him and go back [to his own spot]. That one, soon, with sleep shaken off, should beg pardon with bent knees and, with that same lantern snatched back up, let him circle around the choir himself; and if he should manage to find another compromised by the vice of sleep, he should do to him just as it was done to himself and go back to his own place. (119–20.1392–1401)

As this passage beautifully epitomizes, the circa’s central function was thus to guard against lapses in self-possession. What at first seems like an effort to enforce attentive reading and prayer—by waking the monks sleeping through the lections—instead becomes an exercise in inculcating a broader kind of mental vigilance amid the early morning inducements of bodily lethargy. This explains why the disciplined monks are not watched for further signs of distraction as they continue to attend to the reading but are instead asked to take up the lantern themselves and patrol the choir. Discipline itself is at stake. And bodies in motion not only reanimate hands and knees, lips and eyes, but also rechoreograph the mental gymnastics of monks and nuns before their texts. Rather than regulating distraction and attention per se, or even cultivating the broader obedience Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe has deftly located at the heart of the correction movement, the circa fosters a related, yet distinct, kind of monastic custody (custodia), or unceasing communal and personal supervision meant to cultivate habituated self-possession and discretion, especially in scenes of reading, learning, and performing the liturgy.

Although his public proclamations and nightly rounds might seem to take this to an unnecessarily theatrical extreme, the Concordia and related schoolroom texts from Æthelwold’s circle—namely, the Colloquy by Æthelwold’s prolific student Ælfric, who is now responsible for roughly one-sixth of surviving Old English literature, and the Colloquies by Ælfric’s own student and editor, Ælfric Bata—can thus help us to recover some of the complexities obscured by “attention” and “distraction” as analytical terms with a growing hold on literary studies. Indeed, as Caleb Smith observes, “To call our work reading is to cast it as a discipline of attention”—a framing that, he argues, is particularly prevalent in postcritical methods, which are calibrated “not only against distraction but also, especially, against malign forms of hypervigilance like paranoia and suspicion.” “Passive” textual attention thus becomes an ethical goal, which frees the would-be critic from any charges of violence. But attention and related modalities are neither passive nor impersonal.

Moreover, although distraction and numbness are now too often and easily diagnosed as decidedly modern maladies—particularly as theorized by Walter Benjamin, Georg Simmel, Jonathan Crary, and Paul North—concerned tenth-century schoolmasters were well aware of the temptations of diversions and digressions both in the classroom and beyond it. (After all, digression was a fundamental feature of Old English poems like Beowulf, and monastic thinkers had long grappled with the dangers of distraction.) Somewhat paradoxically, however, even as they worked to develop pointed pedagogic strategies to counter these threats, their texts inculcated self-possession and related self-regulatory goals like continentia (self-restraint) by literally spotlighting its opposite—the dispersal or disintegration of the self—with an impressive flair for the dramatic possibilities of dozing monks and darkened choirs. Confronted with slackened self-regard as an incessant threat to devotional life, monastic writers thus reflected on the problem by composing sometimes-sensational scripts of distraction and mischief, which their students were then required to memorize and perform, much as Bata, Irina Dumitrescu has noted, strategically incorporates violence into his grammar lessons in order to cultivate proper behavior by contrast. They thereby strove to cultivate classroom and liturgical spaces in which students were “distracted from distraction by distraction,” or, at least, by means of scripted lapses in monastic custody, on the side of both the teachers and the students.

In short, the Colloquies and the Concordia together cultivated mental discipline by means of self-conscious performances of its absence. They thus developed a broader model of self-regulation, which sometimes falls between the axes of attention and distraction but is distinct from both. And in the process, they developed a culture of participatory performance, in which the apprehension of knowledge was dramatized and worked through collectively and in which a kind of community theater made legible cognitive activities and self-fashioning processes that are otherwise difficult to conceptualize. As a result, their schoolroom practices are intimately bound up with broader concerns about how to foster self-possession—or, with how to keep the mind and the body focused on things that elude them, whether in the form of a new and difficult language, an intractable text, or even of the disappearance of Christ at the heart of the Easter celebration and, by extension, monastic life.

It is thus no accident that Æthelwold’s Concordia also contains another vivid portrait of a performance at matins: the Visitatio sepulchri, or “Visit to the Tomb,” in which monks and nuns reenacted the scene of the “three Marys”—the Virgin Mary; Mary Magdalene; and Mary, the sister of Lazarus—coming to Christ’s tomb and being informed of his resurrection. Indeed, this scene would also have taken place as dawn was breaking, when the circa and others would busily scan the ranks for wandering minds, and it shares close affinities with pedagogical texts like Ælfric’s and Ælfric Bata’s. Continue reading …

ERICA WEAVER is Assistant Professor of English at the University of California, Los Angeles, where she is currently working on a book about the role of distraction in the development of early medieval literature and literary theory, particularly during the tenth-century monastic “correction” movement traditionally known as the English Benedictine Reform. She is also co-editor, with A. Joseph McMullen, of The Legacy of Boethius in Medieval England: The Consolation and Its Afterlives (Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2018) and, with Daniel C. Remein, of Dating Beowulf: Studies in Intimacy (Manchester University Press, 2020).

ERICA WEAVER is Assistant Professor of English at the University of California, Los Angeles, where she is currently working on a book about the role of distraction in the development of early medieval literature and literary theory, particularly during the tenth-century monastic “correction” movement traditionally known as the English Benedictine Reform. She is also co-editor, with A. Joseph McMullen, of The Legacy of Boethius in Medieval England: The Consolation and Its Afterlives (Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2018) and, with Daniel C. Remein, of Dating Beowulf: Studies in Intimacy (Manchester University Press, 2020).

Manuscript image above: London, British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius A III: Æthelwold, Edgar, and Dunstan bound by text

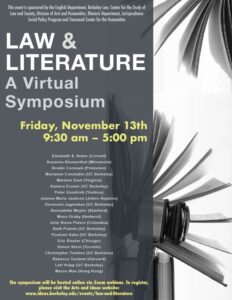

UC Berkeley’s Townsend Center for the Humanities presents an event featuring Representations board members Stephen Best and Debarati Sanyal.

UC Berkeley’s Townsend Center for the Humanities presents an event featuring Representations board members Stephen Best and Debarati Sanyal.

The central regulatory document of the tenth-century English Benedictine Reform, Æthelwold of Winchester’s Regularis concordia, contains an important performance piece: the Visitatio sepulchri, which standard theater histories understand as an anomalous originary text that marks the reemergence of drama in the European Middle Ages. This article resituates it alongside the schoolroom colloquies of Æthelwold’s student Ælfric of Eynsham and his student and editor Ælfric Bata to argue that these texts together cultivated monastic self-possession by means of self-conscious performances of its absence. By staging (in)attention, they thereby modeled extended engagement in moments and spaces that could otherwise seem too quiet or empty to hold concentration for long, from the classroom to the sepulcher to the page, while also exposing the limits of “distraction” and “attention” as analytical terms.

The central regulatory document of the tenth-century English Benedictine Reform, Æthelwold of Winchester’s Regularis concordia, contains an important performance piece: the Visitatio sepulchri, which standard theater histories understand as an anomalous originary text that marks the reemergence of drama in the European Middle Ages. This article resituates it alongside the schoolroom colloquies of Æthelwold’s student Ælfric of Eynsham and his student and editor Ælfric Bata to argue that these texts together cultivated monastic self-possession by means of self-conscious performances of its absence. By staging (in)attention, they thereby modeled extended engagement in moments and spaces that could otherwise seem too quiet or empty to hold concentration for long, from the classroom to the sepulcher to the page, while also exposing the limits of “distraction” and “attention” as analytical terms. ERICA WEAVER

ERICA WEAVER

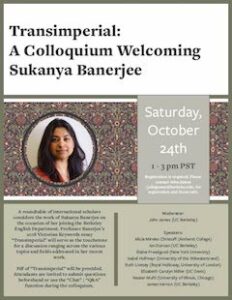

A roundtable of international scholars considers the work of

A roundtable of international scholars considers the work of

David Henkin

David Henkin

Ronit Stahl

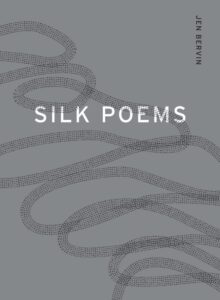

Ronit Stahl Karl Marx’s comments on silk manufacture in “The Working Day” chapter of Capital, volume 1, demonstrate how “quality”—usually associated with “use value”—has been mobilized by capital to naturalize industrialized labor. Putting his insight into conversation with a recent multimedia poetic project, Jen Bervin’s Silk Poems (2016–17), Kathryn Crim examines the homology between, on the one hand, poetry’s avowed task of fitting form to content and, on the other, the ideology of labor that fits specific bodies to certain materials and tasks.

Karl Marx’s comments on silk manufacture in “The Working Day” chapter of Capital, volume 1, demonstrate how “quality”—usually associated with “use value”—has been mobilized by capital to naturalize industrialized labor. Putting his insight into conversation with a recent multimedia poetic project, Jen Bervin’s Silk Poems (2016–17), Kathryn Crim examines the homology between, on the one hand, poetry’s avowed task of fitting form to content and, on the other, the ideology of labor that fits specific bodies to certain materials and tasks.